A new report by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development details the enormous growth in social inequality over the last three decades in the 34 member countries of the OECD, including the US, most of Western Europe and Japan.

The study, “Divided We Stand: Why Inequality Keeps Rising,” examines data from the 1980s until the onset of the global economic breakdown in 2008. The report acknowledges that inequality has only worsened under the impact of the crisis, which has left 200 million workers unemployed globally and universal demands for austerity by governments around the world.

Across the OECD, the average income of the richest 10 percent of the population is now nine times that of the poorest 10 percent. The US remains the most unequal of the industrialized countries, with a gap of 14 to 1, the same ratio as Israel and Turkey. In Italy, Japan, Korea and the United Kingdom the gap is 10 to 1.

According to the report, inequality has risen in what the OECD describes as “traditionally egalitarian countries,” such as Germany, Denmark and Sweden, from 5 to 1 in the 1980s to 6 to 1 today. The biggest chasm in the OECD is in impoverished countries like Chile and Mexico, where the incomes of the richest are more than 25 times those of the poorest.

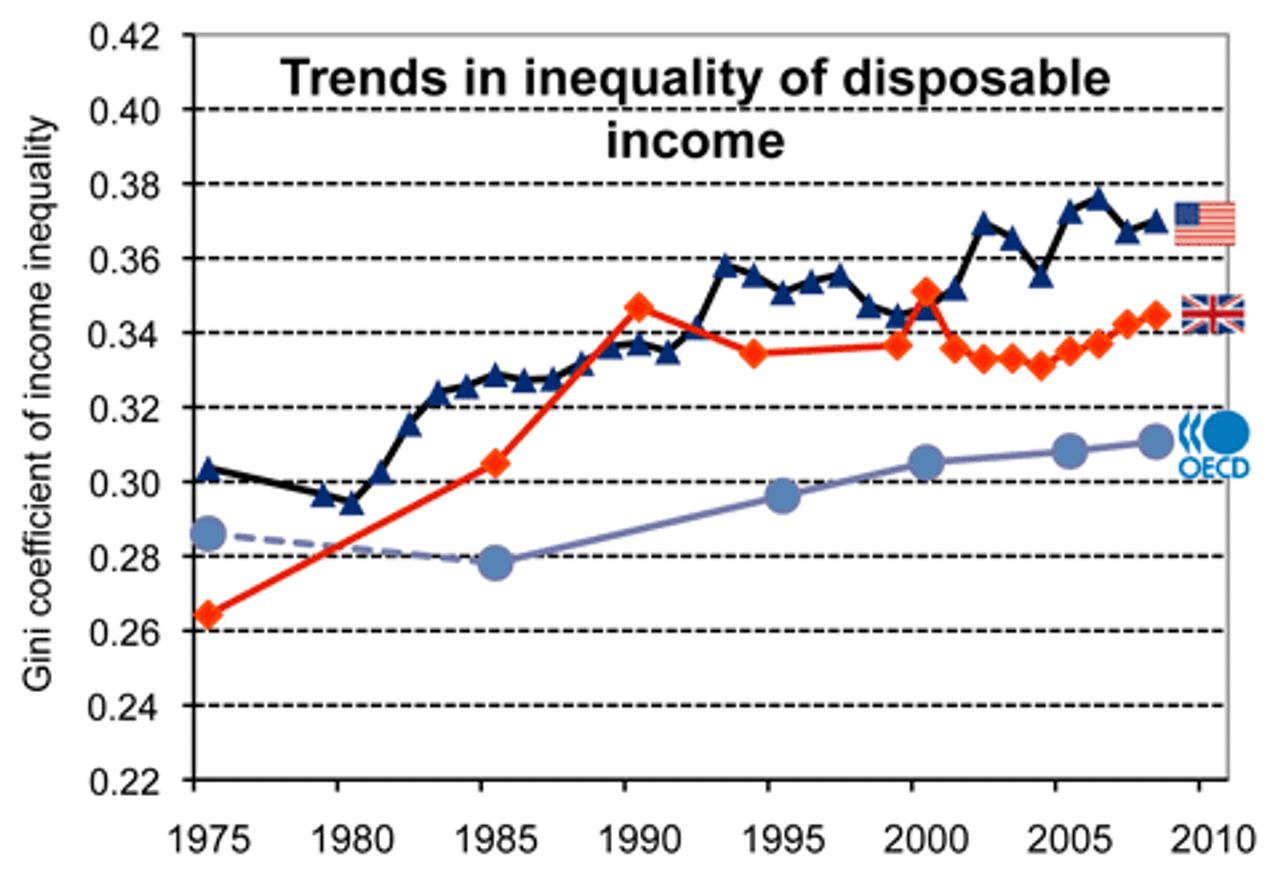

The report examines changes in the Gini coefficient, a standard measure of income inequality that ranges from 0 (when everybody has identical incomes) to 1 (when all income goes to only one person). In the mid-1980s, the coefficient stood at an average of 0.29. By the late 2000s, it had increased by almost 10 percent to 0.316.

The coefficient rose in 17 of the 22 OECD countries for which long-term data series are available, climbing by more than 4 percentage points in Finland, Germany, Israel, Luxembourg, New Zealand, Sweden and the US. Only Turkey, Greece, France, Hungary, and Belgium recorded no increase or small declines in their Gini coefficients.

In addition to the US—where the top 1 percent controls 20 percent of all income, and a far larger proportion of total assets—the concentration of wealth is sharpest in Australia, Canada, Ireland and the United Kingdom. In the US, the share of the top 0.1 percent in total pre-tax income quadrupled in the 30 years to 2008. Just prior to the global recession, the top 0.1 percent accounted for some 8 percent of total pre-tax incomes in the US, some 4-5 percent in Canada, the UK, and Switzerland, and close to 3 percent in Australia, New Zealand, and France.

The OECD—an official body established under the auspices of the post-World War II Marshal Plan—cannot acknowledge that these trends are the result of deliberate class policies. But the late 1970s and the decade of 1980s saw the ruling class abandon the policy of relative class compromise and adopt the most aggressive polices of social counter-revolution.

The Thatcher and Reagan governments launched a wave of violent strikebreaking attacks whose purpose was to break the resistance of the working class to a thoroughgoing redistribution of wealth from the bottom to the top. Deindustrialization and the shifting of production to low-wage countries went hand in hand with slashing taxes on the rich, corporate deregulation and the rise of the most parasitic forms of financial speculation.

The report notes that income inequality “first started to increase in the late 1970s and early 1980s in some English-speaking countries, notably the United Kingdom and the United States, but also in Israel. From the late 1980s, the increase in income inequality became more widespread. The latest trends in the 2000s showed a widening gap between rich and poor not only in some of the already high-inequality countries like Israel and the United States, but also—for the first time—in traditionally low-inequality countries, such as Germany, Denmark, and Sweden (and other Nordic countries), where inequality grew more than anywhere else in the 2000s.”

Between 1980 and 2008, the report continues, “most OECD countries carried out regulatory reforms to strengthen competition in the markets for goods and services and to make labour markets more adaptable.” This is a euphemism for the virtual destruction of all job protections and workplace rights and the transformation of large sections of the working class, with the assistance of the unions, into a largely casualized, part-time workforce.

“All countries,” the report notes, “significantly relaxed anti-competitive product-market regulations and many also loosened employment protection legislation (EPL) for workers with temporary contracts. Minimum wages also declined relatively to median wages in a number of countries between the 1980s and 2008. Wage-setting mechanisms also changed: the share of union members among workers fell across most countries, although the coverage of collective bargaining generally remained rather stable over time. A number of countries cut unemployment benefit replacement rates and, in an attempt to promote employment among low-skilled workers, some also reduced taxes on labour for low-income workers.”

On average across the OECD, the share of part-time employment in total employment increased from 11 percent in the mid-1990s to about 16 percent by the late 2000s, with the strongest increases taking place in some European countries, such as Germany, Ireland, the Netherlands, and Spain.

Over the last three decades, the “top rates of personal income tax, which were in the order of 60-70% in major OECD countries, fell to around 40% on average by the late 2000s,” the report notes. At the same time, “benefits levels fell in nearly all OECD countries, eligibility rules were tightened to contain spending on social protection, and transfers to the poorest failed to keep pace with earnings growth. As a result, the benefit system in most countries has become less effective in reducing inequalities over the past 15 years.”

The OECD concludes with a somber warning that inequality and the lack of social mobility was fueling social discontent, particularly among the younger generation of workers trapped in low-paying, insecure jobs. “Inequality,” the report notes, “breeds social resentment and generates political instability… People will no longer support open trade and free markets if they feel that they are losing out while a small group of winners is getting richer and richer.”

Nevertheless, the OECD could not come up with any prescription other than to appeal to governments to “review their tax system to ensure wealthier individuals contribute their fair share of the tax burden.” Governments, OECD Secretary-General Angel Gurría said at the launching of the report in Paris, had to develop a “comprehensive strategy for inclusive growth.” Expanding education and job training programs, Gurría claimed was “by far the most powerful instrument to counter rising income inequality.”

Such appeals will fall of deaf ears. Every capitalist government, from the Obama administration in the US to the new “technocratic” governments in Greece and Italy installed by the European Central Bank and the IMF, is committed to the most brutal austerity policies on behalf of the financial oligarchy. This only underscores the fact that the most powerful instrument to counter rising income inequality is the expropriation of their wealth by the working class.