This Week in History provides brief synopses of important historical events whose anniversaries fall this week.

25 Years Ago | 50 Years Ago | 75 Years Ago | 100 Years Ago

25 years ago: US meatpacking workers resist corporate offensive

Cudahy strikers in 1987

Cudahy strikers in 1987Almost ten months after the bitter Hormel strike by United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW) local P-9 was shut down by the international union, struggles raged throughout the meatpacking industry against the ongoing corporate onslaught.

About 2,800 locked-out workers at IBP in Dakota City, Nebraska voted overwhelmingly to strike after being locked out since December 13 when they rejected the company’s concessions demands. The IBP lockout was engineered to refurbish the plant without having to pay unemployment benefits. When the company finished the project they began hiring scabs to replace the original workforce.

In Sioux City, Iowa, 800 workers remained out on a strike that began earlier in the month against the John Morrell Company. The strike was provoked by the firing of 37 workers. The company had imposed a concessions contract in February and sought to use the strike to bring in scabs.

Eight-hundred and fifty workers at the Patrick Cudahy plant in Milwaukee, Wisconsin remained on strike in defiance of the company’s severe concession demands. A three-tier wage system and the rollback in seniority rights, health benefits for retirees, and work rules were all part of management’s demands.

Earlier, on March 14, a rally was held in front of the National Guard armory in Austin, Minnesota in support of the 850 former Hormel strikers whose jobs were replaced by scabs. While 600 workers attended the rally, the lack of significant labor support from outside Austin expressed the isolation imposed on the struggle.

50 years ago: Ceasefire ends Algerian war of independence

Leaders of the FLN pictured in 1954

Leaders of the FLN pictured in 1954At noon on March 19, 1962, a ceasefire between France and the Algerian FLN brought to a formal end the Algerian war of independence, which had raged since 1954, killing as many as 1 million Algerians and making another 2 million into refugees.

The war had deeply shaken France. The failure to defeat the FLN militarily had ended the Fourth Republic in 1958, when a threatened coup d'état brought to power Charles de Gaulle. In 1961 it produced a failed putsch by powerful elements in the French military who then formed the extreme-right terrorist organization, the OAS (Organisation armée secrete—Secret Armed Organization). The war became untenable with the growing opposition of the French working class. Only one month before the ceasefire, millions of workers participated in a general strike and 1 million workers marched in Paris against the war, police violence, and the French right. The peace treaty would ultimately be approved by 91 percent of French voters in a referendum.

Unable to crush FLN in Algeria, the de Gaulle government sought to secure property rights for French capitalism and a military presence in a post-independence Algeria. The Evian accords, concluded the day before the ceasefire, secured a privileged position for France in the Algerian oil and gas industry and allowed it to maintain military bases for a period of 15 years. It also provided protections for the French officers, soldiers, and police who had carried out crimes in the brutal counter-insurgency war.

These “concessions” revealed the limits of the bourgeois nationalism advanced by the FLN and its leader Ben Bella, whose overriding concern was to secure the privileges a narrow native elite. While major French capitalist interests were protected, the FLN soon oversaw the dispossession of the French Algerian and Jewish populations. About 1.5 million would flee Algeria for France within a year.

The OAS sought to scuttle the truce by launching a new wave of terrorist attacks against Arabs. On March 20, OAS fighters launched mortar shells into the Casbah district of Algiers, killing four and wounding 67.

75 years ago: UAW ends Chrysler Detroit sit-down strike

Worker musicians during REO occupation in Lansing,

Worker musicians during REO occupation in Lansing,Michigan, 1937

On March 25, 1937, the 6,000 sit-down strikers who occupied Chrysler’s Detroit plants vacated the factories. The United Auto Workers (UAW) ordered an end to the 17-day strike when Walter P. Reuther and John L. Lewis of the Committee for Industrial Organization (CIO), under pressure from the Roosevelt White House, struck an agreement officially recognizing the UAW. Negotiations on issues of wages and working conditions would continue only after the evacuation.

An American correspondent for the London Times commented, “After years of ineffectual struggling to win even so much as a foothold in the country’s largest industries organized labor has attained overnight, as it were, a position of power over them that could hardly have been dreamed of by an older generation of workers.” The correspondent also speculated that the level of militancy amongst the US workers might lead to the formation of an American Labor Party.

The intervention by Roosevelt and the move by the CIO and the UAW to stop the Chrysler sit-down came as the workplace occupation movement threatened to transition into a nationwide general strike. A day earlier, on March 24, the UAW called a demonstration to “show labor’s strength” attended by 60,000 workers. In both Detroit and New York sit-down strikes were breaking out sporadically amongst workers in all sectors of the economy. Emulating their counterparts in Detroit, the mainly female employees of Woolworths in Brooklyn and Long Island, New York, occupied their places of work

100 years ago: The Battle of Rellano

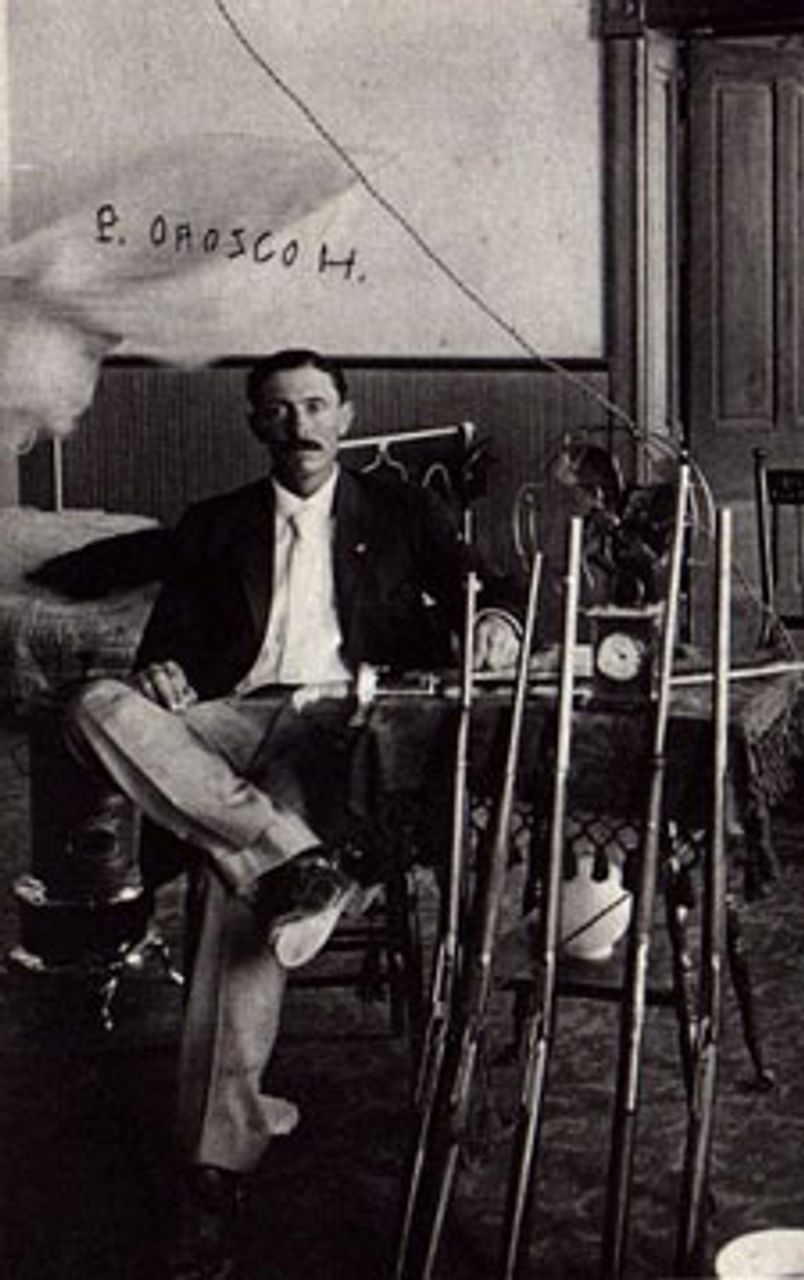

Pascual Orozco

Pascual OrozcoOn 24th March 1912, the Battle of Rellano began when the state of Chihuahua rebelled against federal troops representing the Mexican government. The battle was part of the Mexican Revolution of 1911 to 1920, which had begun as an uprising led by Francisco I. Madero, Pancho Villa and Emilio Zapata against the dictator Porfirio Diaz.

Madero became President in 1911 but failed to deliver on his promises of land and social reforms, causing Zapata and Pascual Orozco to turn against the government they had initially supported. With 95 percent of the land owned by less than 5 percent of the population, the landless peasants, small farmers and the working class demanded a change of leadership. Workers and peasants threw their support behind Orozco and Zapata, who urged a rebellion against the Madero government.

Orozco decreed a formal revolt against the Madero government in March 1912, and on March 24 government troops led by General Jose Gonzales Salas fought rebel troops under Orozco at Rellano railroad station.

Orozco’s rebel troops won the battle and Salas committed suicide in the aftermath of the federal troops’ retreat. With this victory, Orozco assumed control of all of Chihuahua, except Parral, which was held by troops loyal to Pancho Villa. Orozco eventually succeeded in taking Parral, but the resistance of Villa’s troops allowed enough time for General Victoriano Huerta to arrive with a new federal army. This led to the second Battle of Rellano on May 12, in which Huerta defeated Orozco, who subsequently sought refuge in the United States.