Zoe Strauss: Ten Years—An exhibition of photographs at the Philadelphia Museum of Art and The Billboard Project, January 14-April 22, 2012

American photographer Zoe Strauss (b. 1970) is an unusual figure in today’s art world. In 2001, she put 30 photographs of working class people up on the support columns under I-95—the elevated interstate highway that bisects her south Philadelphia neighborhood—for a one-afternoon exhibit. Strauss says the idea came to her before she even owned a camera, but from the outset she conceived of “I-95” as a 10-year endeavor to tell an “epic narrative about the beauty and struggle of everyday life.”

Now, 10 years on, Strauss’s “I-95” project has culminated in a solo exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, which ends April 22. The show of 170 photographs, selected from thousands, is not only a summation of the project, it is an opportunity to view the narrative as a whole, and ask, “What story has Strauss told?”

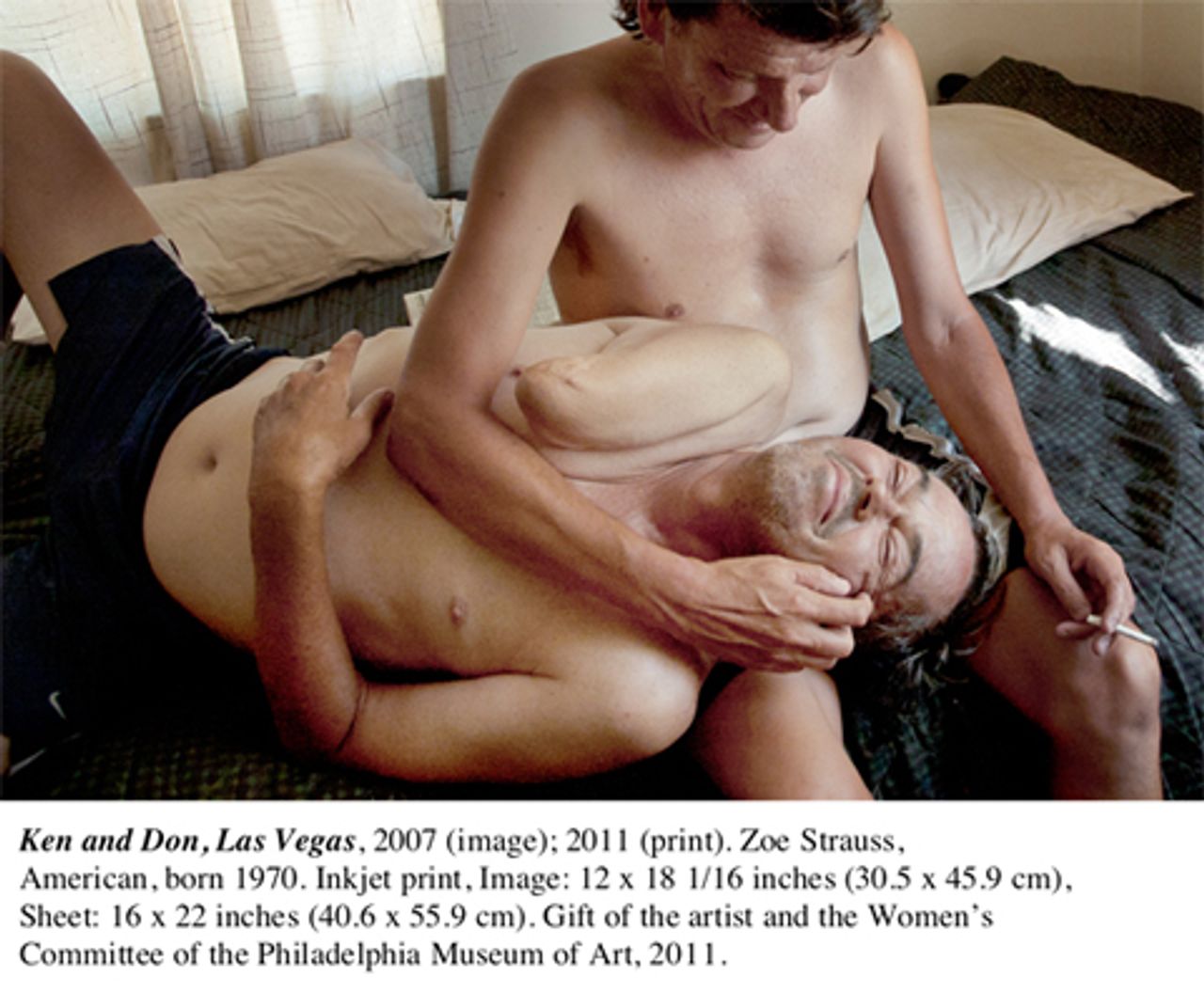

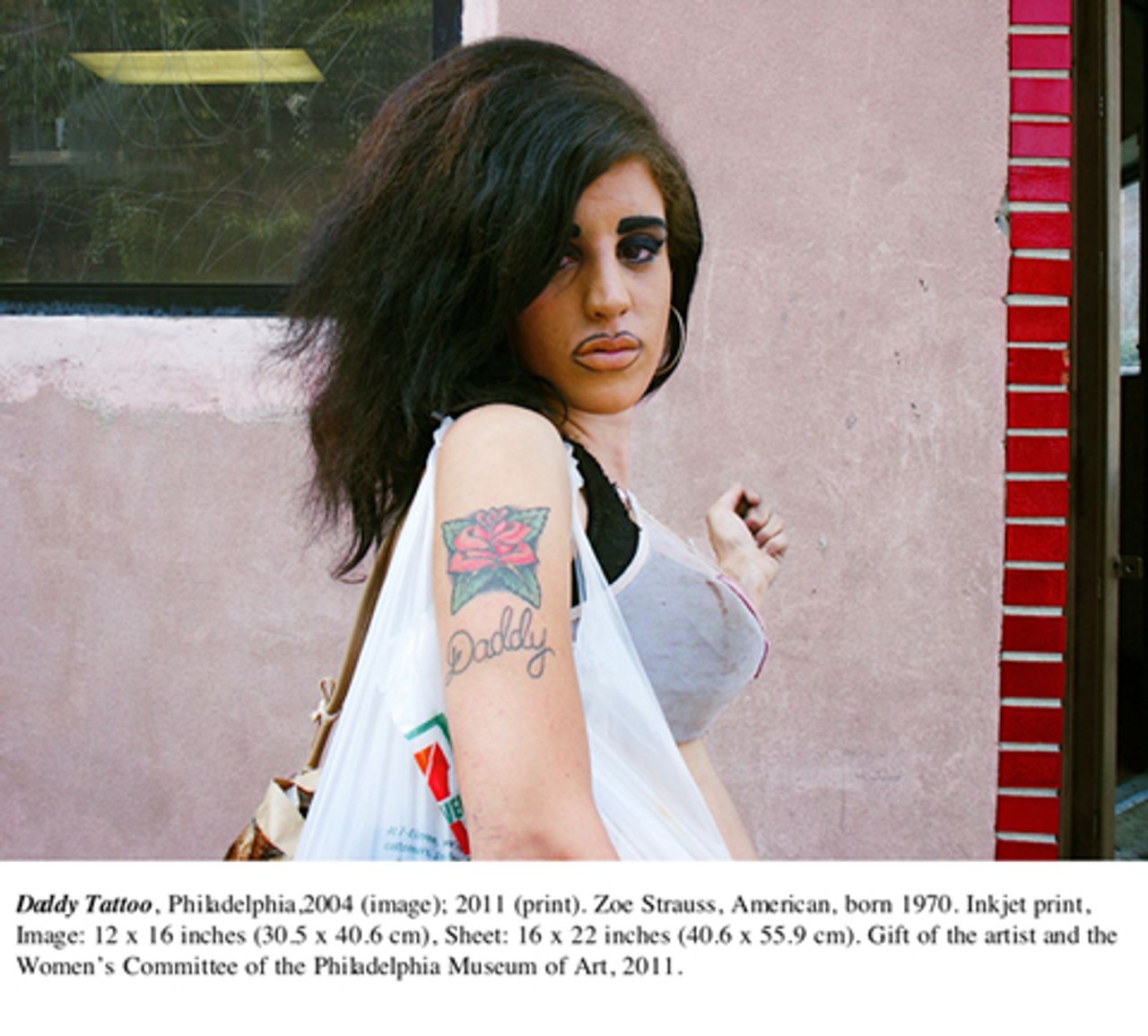

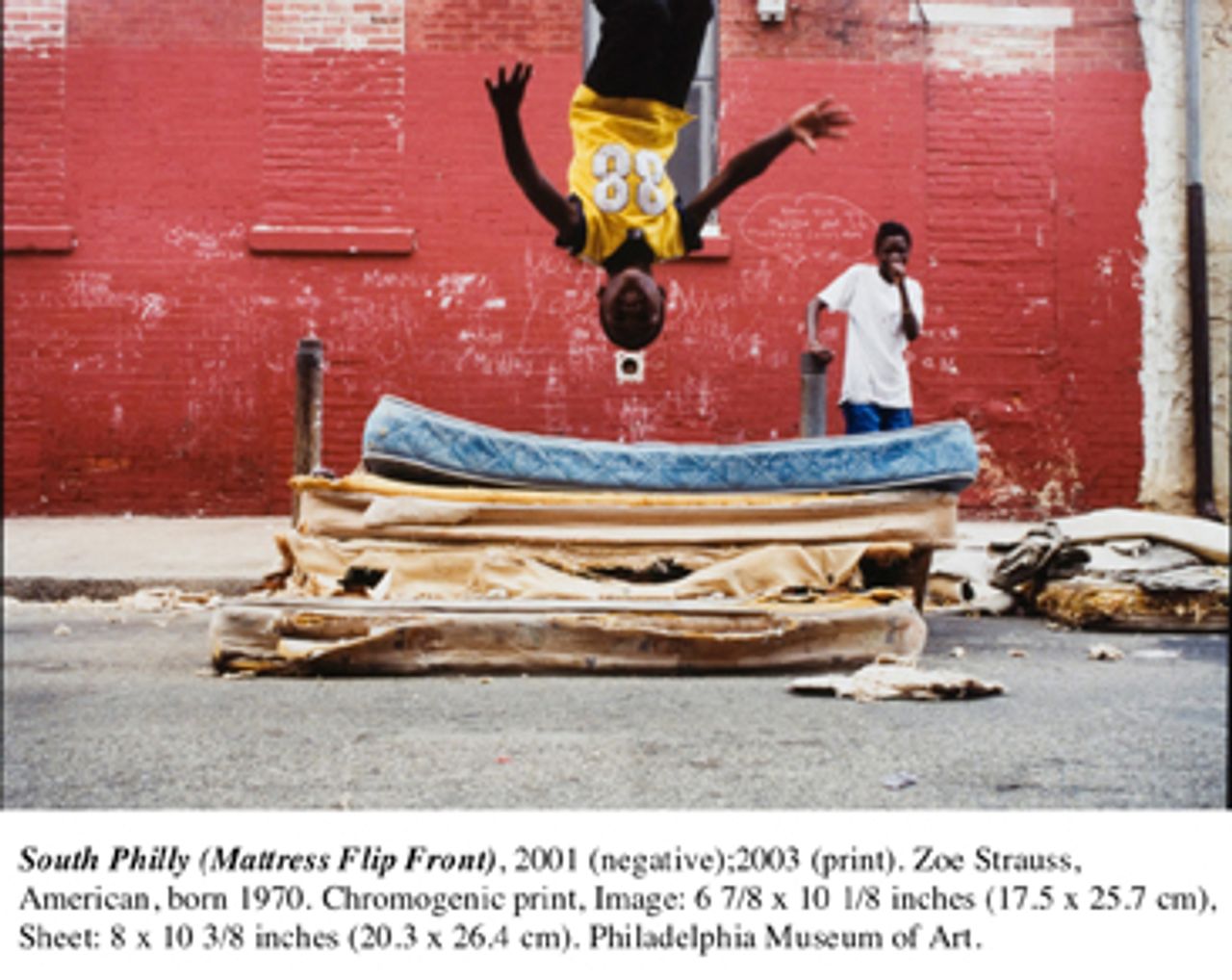

Her portraits of the people upon whose faces and bodies this epic narrative is written—often quite literally in wrinkles and make-up, scars and tattoos—are unsparing, yet empathetic. Her subjects often expose parts of their bodies in the most revealing manner, or conversely wear a mask, or strike a defiant pose, as if to say, “This is who I am—or choose to be—take me or leave me.”

In addition to the portraits, Strauss has an eye for the unconventional beauty of the urban American landscape. This often results in wry commentary on her narrative—from ironically placed or misspelled advertising to hand-written signs and graffiti.

In the period immediately after the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center, a motel sign reads, “All Americans its time to be close,” with all the implied double meaning of the final word. Or a dollar store sign reminds us “Not everything is $1.”

And finally there are photographs of either striking formal or natural beauty, or both, many suggesting the after-effects of momentous events: the blown-out Venetian blinds of a house in Biloxi, Mississippi, in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, an unnatural sheen on the Gulf of Mexico after the BP oil spill, or simply the traces on a wall of posters that once hung there.

The story of the “I-95” project itself indicates Strauss’s formidable dedication to creating her portrait of American life. This includes a commitment to sharing intimate aspects of her personal life and artistic progress, much the same way her subjects unreservedly bare their various scars. Throughout the project, she has maintained an online blog where she communicates on a wide range of topics from the private to the political.

Unlike the casual anonymity of much street photography, Strauss often shares the circumstances in which the photos were taken, and, in some cases, discloses what has happened to her subjects. For instance, the audaciously made-up young woman in Daddy Tattoo (2004) is re-encountered in Monique Showing Black Eye (2006), and we then learn, sadly, that she died later that year.

From its modest beginnings in 2001, Strauss’s annual exhibit under the interstate highway each May grew to include 231 photographs, and drew visitors from across the US and beyond. In keeping with her goal of accessibility, inkjet prints of the photographs were sold at the exhibit for $5 each, because “that’s what people can afford.” At the end of the exhibit, the prints on the columns could be taken for free.

In 2006, Strauss was included in the Whitney Biennial (the exhibition of contemporary work generally regarded as one of the art world’s leading shows), which was considered among the more incisive that year, primarily for the number of works reflecting anti-war and other socially critical sentiments. But even in that context, Strauss’ work stood out.

(See “Interview with Zoe Strauss: photographer in the Whitney Biennial: Day for Night.”)

Before her inclusion in the Biennial, Strauss had received support from the Pew Foundation and other Philadelphia-based arts organizations, particularly the Institute of Contemporary Art. After the 2006 Whitney show, her work received increasingly broad attention.

Since 2007, she has had two solo shows at the Bruce Silverstein gallery in New York, as well as other galleries in the US and Europe, received an Agnes Gund Fellowship in 2007 and published a book of her photographs, America, in 2008.

Additionally, she has participated in residencies that have taken her to Anchorage, Alaska, and in curatorial workshops in Madrid, Spain, in 2009. In 2010, she initiated the On the Beach project to photograph the results of the BP oil spill in the affected areas of Louisiana and Mississippi.

Now with a solo show at the Philadelphia Museum as a living artist just turned 40 years old, Strauss could be said to have mounted the steps of the academy, literally. Proud of being self-taught, Strauss’s work is not without its precedents, and she readily acknowledges wide-ranging influences.

As a street photographer, Strauss’s work continues the documentary approach pioneered by French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson (1908-2004), whose small 50-mm Leica camera enabled him to capture daily life with such immediacy that he considered it an extension of his eye.

Visual references to images of other artists and photographers abound—the latter include French painter Edouard Manet (1832-1883), as well as American photographers Catherine Opie (b. 1961), William Eggelston (b. 1939) and Gordon Matta-Clark (1943-1978).

She has been compared, superficially, in my view, to photographer Diane Arbus (1923-1971) because of her interest in photographing society’s marginalized—particularly the homosexual or transgender. But while Arbus’s photographs often seem to emphasize the freakish aspects of life, Strauss’s tend to humanize it.

Perhaps nearer in spirit is the work of Swiss-born photographer Robert Frank (b. 1924), to whose photographs The Americans (1958) Strauss’ America directly responds. Frank’s black-and-white photographs of the “broad middle” of US life—characterized prominently by American flags, automobiles and darker aspects such as racial segregation—critiqued the official image of American prosperity and “success” in the 1950s.

However, Strauss’s exclusive focus on the social conditions of poor and working-class life brings her even closer to Walker Evans and the photography sponsored by the Works Progress Administration, with its roots in the left-wing intelligentsia of the 1930s. Except that Strauss’s work does not seem intended to appeal to the conscience of well-meaning progressives. Rather, its attitude is more like the angry graffiti on the side of a building: “If you reading this, ***k you.”

As a self-defined lesbian-anarchist, Strauss identifies strongly with identity politics, and it has been partly on these terms that some of her success has been won, particularly since Barack Obama’s election in 2008, about which she was enthusiastic.

But the contradiction and main strength of Strauss’s work is that it does not present race, gender and sexual orientation as the defining characteristics of her subjects. Their unifying characteristic is their class—she herself declares no interest in photographing middle- or upper-class life. (Though to do so with the same unsparing approach would ultimately give her narrative a fuller range.)

Her photographs tell the epic narrative of the American working class over the past decade—a decade that has seen two wars, various environmental disasters and an economic collapse unprecedented since the Great Depression. The people in her photographs bear scars from all forms of violence and deprivation—over the course of the project, a few have died from drugs or in street shootings.

However, their demeanor is angry rather than despairing, resourceful in the face of adversity and lit up by flashes of defiant humor and ineffable tenderness.

Strauss sums up her own work with a motto taken from a billboard advertising an AIDS prevention clinic: “If you break the skin, you must come in.” And indeed, once one has engaged with her photographs, one is “in.” Her images expand our understanding of the world and register the transformations, if not yet entirely made conscious, of the past decade.

To see more images, visit http://www.philamuseum.org/exhibitions/745.html

Notes:

The exhibit is accompanied by the publication Zoe Strauss: Ten Years. Photographs and critical essays, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2012 (ISBN: 978-0-87633-234-4)

In addition to the exhibit, roughly 50 of Strauss’s photographs were put up on billboards around the neighborhoods of Philadelphia as part of The Billboard Project. These can be seen here: http://zoestraussbillboardproject.com/