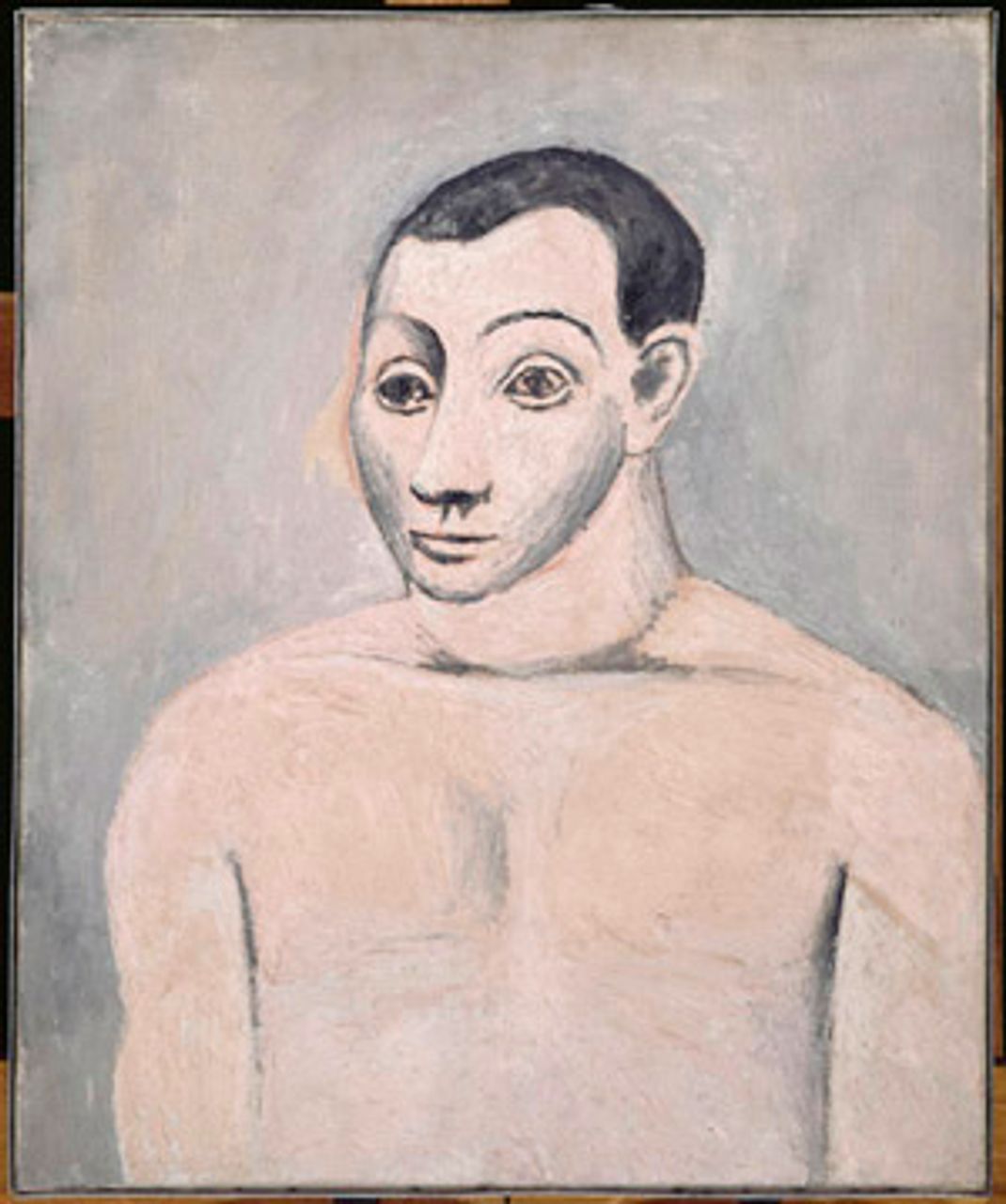

Autoportrait (Self Portrait), 1906. Oil on canvas

Autoportrait (Self Portrait), 1906. Oil on canvasMusée National Picasso, Paris

© Picasso Estate SODRAC (2012)

© RMN/ RenéGabriel Ojéda

Picasso: Masterpieces from the Musée National Picasso, May 1—August 26, 2012, the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO)

Pablo Picasso’s name is virtually synonymous with modern art, and while public opinion may vary, and for varying reasons, the world generally continues to stand in awe of his enormous body of work. Notwithstanding the veneration he still tends to inspire, questions remain about his legacy and the evolution of modern art in general. There is also the matter of Picasso’s political role, often passed over in silence or treated uncritically.

The current exhibition at the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO) is the largest of Picasso’s work to be held in Canada in almost 50 years, bringing together nearly 150 paintings, sculptures and prints from his own collection of over 5,000 works now housed at the Musée National Picasso in Paris. On its only Canadian stop on a world tour, the Toronto show is supplemented by the AGO’s own holdings of prints and drawings by the artist. All of this adds up to an impressive and representative display of Picasso’s output.

Whatever one’s view, the breadth, volume and virtuosity of his work, as is well in evidence in this exhibition, beggars comparison with that of any other painter in the last century. At the same time, the mystifying designation of genius, the wildly irrational monetary value generated by art market speculators and the vying political interests that come to bear, make a sober consideration of his life and work difficult…but not impossible.

For those who profess a dislike of Picasso, one is obliged to ask—which Picasso in particular? The artist himself eschewed identification with any single school of painting and moved readily between various styles throughout his career. Along with Georges Braque (1882-1963), he is credited with the creation of cubism, with which he remains closely identified in popular perception. The dramatic use of planes and geometric form, as shown in many of the works included in this exhibit, became a watershed in both the development of modern art and attitudes toward it.

While I have always admired this artist for his consummate skill and unparalleled versatility, these merits too often overshadow a deeper artistic appraisal of his work. There are, of course, numerous examples of exceptional and important achievements, but much of the art presented in this show would be better approached in the spirit in which one supposes it was created, as experimental play.

Virtuosity at play

Since the work of Picasso has collectively provoked perhaps more comment and analysis than any artist of the past century, one further artistic assessment seems gratuitous. I will nevertheless profess a particular admiration for a number of his sculptures shown here, such as “Head of a Woman (Fernande)” (1909), a powerful and even martial depiction of femininity that stands in contrast to much of his sexual fascination with his female subjects.

His life-size bronze, “The goat” (1950), is a classic of modern sculpture and one variation on the animal that the artist depicted in various media throughout this period. Originally cobbled together from found objects, it remarkably captures the essence of the goat, but as human construct. Unlike other artists who used objects as meaningful references in their work, Picasso had no such concern, but rather chose everyday objects purely for the shapes they offered, such as a basket for a belly in this sculpture, or clay urns for the udders.

Deux femmes courant sur la plage (La Course) (Two Women Running on the Beach [The Race]), 1922. Gouache on plywood

Deux femmes courant sur la plage (La Course) (Two Women Running on the Beach [The Race]), 1922. Gouache on plywoodMusée National Picasso, Paris

© Picasso Estate SODRAC (2012)

© RMN/JeanGilles Berizzi

Though often regarded as a self-serious egoist, Picasso was also very much an iconoclast and scamp, according to some who knew him best. Contrasting the typically impassive expressions featured in many of his portraits, there are a number of paintings—such as “Two Women Running on the Beach” (1922)—that evince the more playful aspect of his character.

Conversely, and despite some epic qualities and numerous historic reference points, much of his work arises from and expresses his own personal difficulties. Seen as a precursor to his iconic “Guernica” (1937), his series of etchings entitled “The Minotauromachy” (1935), one of which appears in this show, is a complex piece encompassing many of his mythological themes including the Minotaur and the crucifixion. Violent and horrifying, this project was preparatory to his political radicalization, but was as much a response to the troubles of his personal love relations as to the events unfolding in Spain at that time.

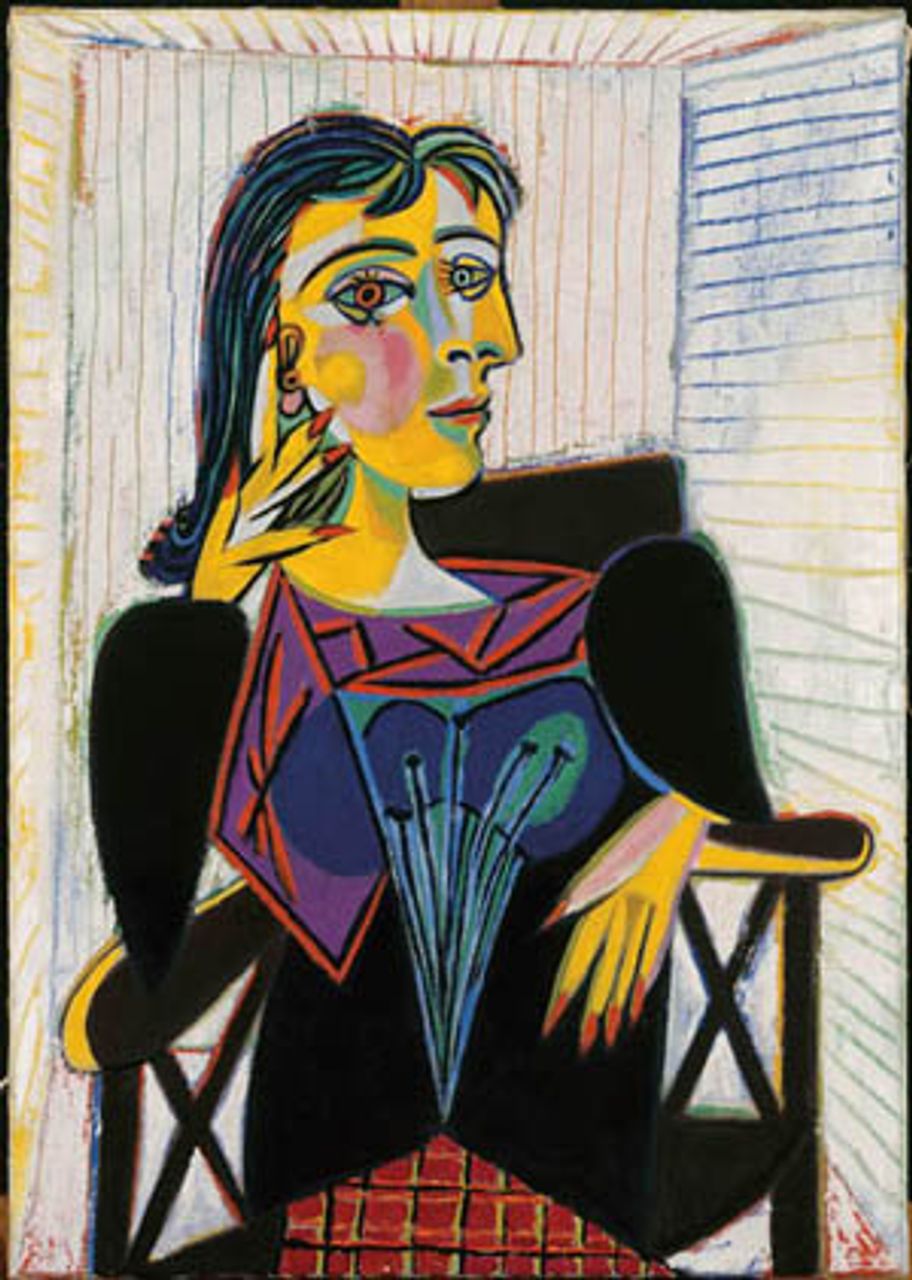

Portrait de Dora Maar (Portrait of Dora Maar), 1937.

Portrait de Dora Maar (Portrait of Dora Maar), 1937. Oil on canvas

Musée National Picasso, Paris

© Picasso Estate SODRAC (2012)

© RMN/JeanGilles Berizzi

The confounding portrait of Dora Maar is of special note in this collection, both for its brilliant duality of expression, and for the relationship of the artist to his subject. Maar was an artist and photographer in her own right and, as his longtime lover, also became a considerable influence on Picasso politically, for better or worse.

The modern incarnate

As an adolescent, Pablo Ruiz Picasso (born 1881 in Malaga, Spain) was already mastering classical and academic art, learning drawing skills in the mold of Raphael and imitating the likes of Delacroix with startling proficiency in his painting. His father, an art teacher by profession and his dedicated tutor, is alleged to have declared that as a student his son had already surpassed his master by the age of 13.

By his early twenties, he had developed his own masterful hand in the darkly lyrical images of what has become known as his “Blue Period.” To my mind, these paintings, which deal with the tragic conditions of the poor and the socially outcast, stand as his most successful and moving work. One of the most powerful paintings in this exhibit is “La Célestine” (1904), a dignified but haunting portrait of a partially blind woman in the somber blue tones for which the period is named.

La Célestine (La Femme à la taie) (Celestina), 1904.

La Célestine (La Femme à la taie) (Celestina), 1904. Oil on canvas

Musée National Picasso, Paris

© Picasso Estate SODRAC (2012)

© RMN/ Rights reserved

In distinction to much current art practice, Picasso worked tirelessly to assimilate the fundamentals of painting craft and expression before his departure into uncharted territory. It was likely to his benefit that he was not exposed to the breakthroughs made by the Impressionist and Post-Impressionists of the late nineteenth century until he had gained a technical maturity, as early as that was in his case.

Prior to his contact with the higher abstraction he encountered when he first visited Paris at the turn of the century, Picasso was strongly affected by the work he had gained a great affinity for at the Prado Museum in Madrid from the age of 16. Of particular interest to him were the paintings of El Greco (1541-1614) and Goya (1746-1828). For very different reasons, both are regarded as pioneers in charting a course for what was to develop as “modern” art.

By 1902, Picasso was living in Paris, where he would spend most of his life and where he soon gained recognition. First, he drew the attention of fellow artists who recognized his towering talent, but by the outbreak of the First World War he had achieved prominence throughout the art world.

He continued to work energetically with marvelous bursts of creativity even into his eighties. Thematically, he returned to many of his earlier subjects, and while most of the work through this period is unremarkable, much of his later output included in this display is still appealing for its whimsy and superb draftsmanship.

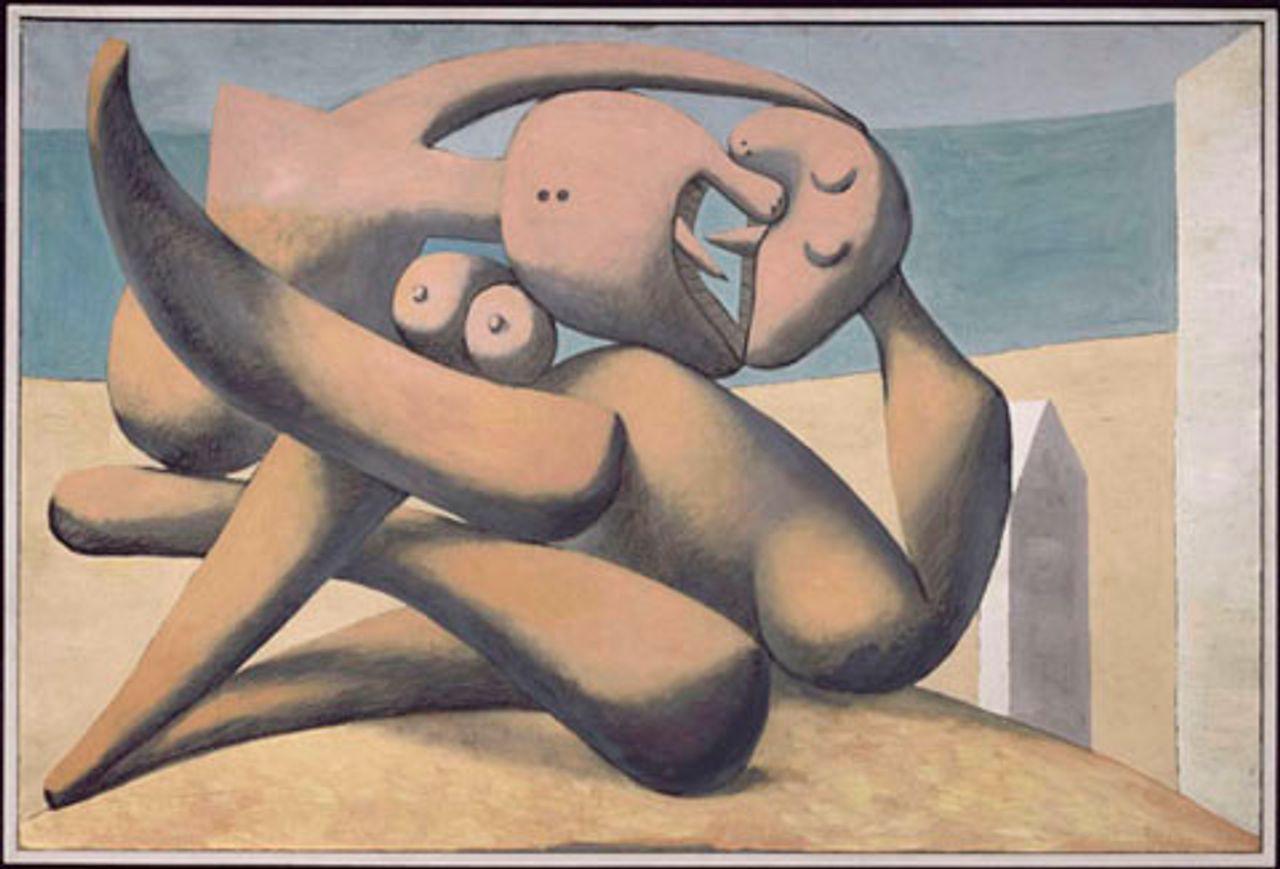

Figures au bord de la mer (Figures on the Seashore), 1931. Oil on canvas

Figures au bord de la mer (Figures on the Seashore), 1931. Oil on canvasMusée National Picasso, Paris

© Picasso Estate SODRAC (2012)

© RMN/RenéGabriel Ojéda

Famous as a prolific innovator throughout his career, Picasso made no apologies for what has been characterized as his thievery of other artist’s ideas and innovations. In his defense, he countered such charges with the now famous quote, “bad artists copy—good artists steal.”

Yet there are many who, while acknowledging his prolific genius, view other artists of his time as achieving equal or even greater innovation and even in the styles that he is credited with developing. The case has been made for example that the cubist works of Braque have greater depth and conviction than those of his collaborator Picasso. Whatever the case, and his legendary conceit aside, his work was part of the modern transformation of art that he both fed on and contributed to profoundly.

A political naïf

Unlike many of his contemporaries who put their energy into revolutionary and anti-capitalist movements during the upheavals of the early twentieth century, Picasso avoided any sort of political alignment for the first half of his life. He lived and worked through the First World War, the Russian Revolution and the rise of fascism apparently without being much troubled by the fate of the world, although numerous friends and colleagues were socially and politically engaged.

Some of his work of the interwar years has been called surrealist, but Picasso never subscribed to the principles of that movement. Avoiding the revolutionary strivings of the surrealists led by André Breton, who were keen to claim him as one of their own, he took from the movement only what he saw as useful to his art. Though he made use of its insights into the unconscious in art and his work was even included in some of their exhibitions, Picasso was no surrealist.

Portrait d’Olga dans un fauteuil (Portrait of Olga

Portrait d’Olga dans un fauteuil (Portrait of Olga in an Armchair), 1918. Oil on canvas

Musée National Picasso, Paris

© Picasso Estate SODRAC (2012)

© RMN/RenéGabriel Ojéda

It was not until the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936 that he publicly came to life politically. When cherished art works housed at the Prado Museum were threatened with attack from Franco’s fascist forces, Picasso was finally stirred to action, and then it was to the Spanish and French Stalinist parties that he gave his support. He mistakenly came to regard the Communist Party (and the Soviet Union) as a bulwark against reaction, and though he did not officially join until 1944, he maintained his allegiance to the Communist Party of France until his death in 1973. The affiliation was mutually exploitative, each party seeking a measure of prestige and credibility through the association.

That he remained silent through the brutal Stalinist repression of the Hungarian Revolution and the invasion of Czechoslovakia, always with eyes closed to the historic crimes of Stalinism in liquidating a generation of Marxists—these are no small matters, although he was hardly alone in this. While he readily declared himself a Communist at a time when such an identification meant the ruin of so many artists, it cost him little since his place among the European cultural elite was by then unassailable.

And yet his extraordinary painting of Guernica, the Basque town viciously destroyed by Nazi bombardment in 1937, remains among the most well-known and potent political art works of the century, and a number of photographs by Maar are shown in this exhibit that document its development.

There is little else said about his political role in the catalogue accompanying this exhibit, where his views are generally treated as idiosyncratic. This is largely a means of avoiding the complex problems of art and social revolution in the twentieth century when it is not merely a concession to anti-communism.

Violon (Violin), 1915. Construction: sheet metal,

Violon (Violin), 1915. Construction: sheet metal, cut folded and painted, wire

Musée National Picasso, Paris

© Picasso Estate SODRAC (2012)

© RMN/Béatrice Hatala

In practical terms, Picasso’s outlook and activism never rose much above pacifist and protest politics. Nonetheless, it is impossible to disconnect his immense and contradictory contributions to modern art from the opposition to the existing social order, including its art world, that was felt within wide layers of the intelligentsia in the first decades of the past century. The complex mix of a great artist’s attraction to socialism and the cause of the working class, on the one hand, and accommodation to the Stalinist bureaucracies, on the other, is a problem that needs further consideration (viz. Brecht, Chaplin, Dreiser and others).

An uncritical and merely awe-inspired approach to Picasso, and the entire course of art in the twentieth century, has limited value. To dismiss him as a charlatan or showman would be even worse. The immensity and genius of his work is unquestionable. The problems bound up with his art, and its relation to the great events of the last century, are perhaps equally immense.

There is no doubt that Picasso’s art will continue to inspire, intrigue and sometimes infuriate for generations. At the very least, his contradictory role should encourage the further exploration of the relationship of artists and their art to a world in revolt.