This Week in History provides brief synopses of important historical events whose anniversaries fall this week.

25 Years Ago | 50 Years Ago | 75 Years Ago | 100 Years Ago

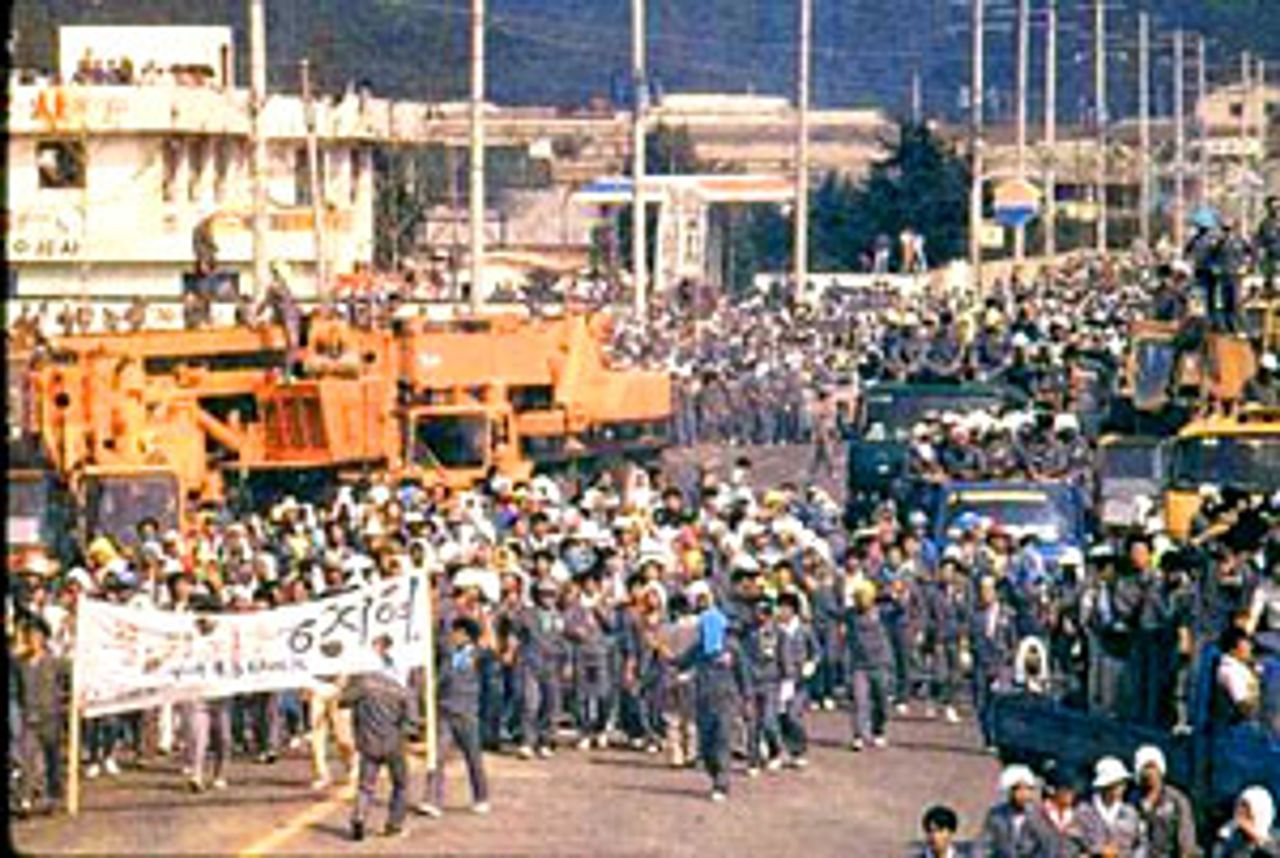

25 years ago: Strike wave erupts in South Korea

South Korean workers in the streets

South Korean workers in the streetsEighteen new strikes broke out in South Korea on Thursday, August 6, 1987, bringing the total to 54. Sit-down strikes were widespread as workers waged pitched battles with police across the country. Strikers demanded higher wages and the right to organize unions without government interference, instead of the management-run company unions set up under the military dictatorship of Chun Doo Hwan.

Fifteen thousand workers seized control of the Hyundai Heavy Industries shipyard in Ulsan, largest in Korea. Chun Du-Young, owner of the Hyundai group, was captured and held prisoner by workers for two hours, released only after he made a speech promising “the maximum possible pay raises” in contract talks in September headed by new unions to be formed democratically.

The strike wave gained enormous support as the week progressed, spreading to the auto industry and swelling the number of strikers to the hundreds of thousands and affecting additional hundreds of thousands who were locked out due to lack of parts and supplies.

The powerful movement of the working class exposed the fragile character of the regime in South Korea. Since 1945, when the country was set up as an anticommunist bastion by US imperialism, dividing the peninsula nation, the industrialization of South Korea was based on some of the most exploitative conditions in the world. By 1987, South Korean workers had the longest workweek in the world, averaging 57 hours, while being paid an average of $1.75 an hour. This ruthless exploitation was the basis of the country’s “economic miracle.”

The determination of the young Korean working class to combat the forces of the state and the military struck terror into the regime of newly-elected General Roh Tae Woo and its imperialist patrons. The strike wave followed barely two months after massive student protests that rocked the country. Roh ominously declared that the regime was “watching very carefully” what he claimed were “outside forces” agitating for strikes. The previous military coups of 1961 and 1980 came largely in response to strike waves.

50 years ago: Army factions take Argentina to brink of civil war

Jose Maria Guido

Jose Maria GuidoCompeting factions of its military command took Argentina to the brink of civil war this week in 1962. Major General Federico Toranzo Montero, who had set up a rebel headquarters in northern Argentina, on August 8 declared himself commander-in-chief of all armed forces. Montero massed his soldiers at a defensive position in the suburb of Palermo, and his allies took control of the war ministry building.

These events brought the resignation of War Secretary and army high commander General Juan Bautista Loza after it became clear that he lacked sufficient support in the military brass. President Jose Maria Guido then appointed General Eduardo Senorans as the new commander in chief. Senorans wanted a showdown with Montero, but was reined in by Guido, and retired ten hours after having been sworn in on August 9.

On August 10 opposing soldiers, tanks, and artillery arrayed against each other in Buenos Aires. The Air Force announced it would block direct confrontation by threatening to attack the troops of the rival generals. The Navy also deployed armed sailors to block the movement of troops loyal to Senorans, whose supporters controlled the key Campo de Mayo installation in Buenos Aires. On August 11, President Jose Maria Guido appointed a new army secretary acceptable to the feuding factions, Gen. Jose Saravia, temporarily defusing the situation.

The dueling factions were each described as anti-communist, anti-Peronist, nationalist, and right-wing. In the words of the New York Times, the dispute was in part over the spoils of military service and “over how strong to be in quashing Communists and putting down adherents of the former dictator, Juan D. Peron.” Additionally, the Montero faction opposed the austerity plan of Economics Minister Alvaro Alsogaray, which had been launched to deal with a severe financial crisis.

Guido had been installed in March after the army ousted his liberal predecessor, Arturo Frondizi. Guido’s government had already banned Peronism and had annulled Peronist victories in the March 18 elections.

75 years ago: Japanese army enters Beijing

General Mazakazu Kawabe

General Mazakazu KawabeOn August 8, 1937 the Chinese city of Beijing (Peking) fell to the Imperial Japanese Army without resistance. Japanese General Masakazu Kawabe declared himself military governor of the city a few days later, after a Japanese military parade through the ancient capital of China.

During late July, in a series of military clashes referred to as the Battle of Peking-Tianjin, the Japanese China Garrison Army took the city of Tianjin and the port of Tanggu. Chinese troops retreated south along the Beijing-Tianjian and Beijing-Hankow railways. With the Japanese military increasingly surrounding Beijing, the leader of the nationalist Kuomintang Party, Chiang Kai-shek, ordered General Liu Ruzhen’s troops to withdraw from the city and its surrounding districts to Chahar.

The Second Sino-Japanese War broke out after an accidental clash between Chinese and occupying Japanese troops on military maneuvers in an event now known as the Marco Polo Bridge Incident. The bridge named after the famous Venetian traveler is otherwise known as the Peking-Lungou Bridge and is located on the periphery of the walled city of Wanping, southeast of Beijing. The bridge was crucially located at the choke point of the Pinghan railway whose strategic importance lay in its being the only passage linking Beijing to the Kuomintang-controlled areas in the south China.

Japanese forces subsequently swept south and west from occupied Manchuria (Manchukuo), beating the best divisions of the Kuomintang armies en route. Japanese forces had occupied Manchuria since 1931.

A year before Beijing fell, in August 1936, the Japanese government adopted the “Fundamental Principles of National Policy.” These imperialist geo-political designs, according to historian William Keylor, “foresaw the economic integration of Japan, Manchukuo, and Northern China, the economic penetration of Southeast Asia, and acquisition of undisputed naval primacy in the Western Pacific. In order to protect its northern flank from possible Soviet interference with this southward expansion, the Japanese government signed the so-called Anti Comintern Pact with Nazi Germany in November 1936 to intimidate Moscow.”

100 years ago: Albanians revolt against Ottoman rule

Isa Boletini and other Albanian revolutionaries after

Isa Boletini and other Albanian revolutionaries afterthe declaration of independence

On August 12, 1912, Hasan Prishtina and Ismail Qemal Bey led 20,000 Albanian tribesmen to seize Skopje in Macedonia. Their aim was to merge Kosovo and the vilayets of Monastir/Bitola (modern Albania) into an autonomous Albanian region in their struggle against the Ottoman Empire. Local disturbances that developed into the Albanian rebellion against the Ottoman Empire had begun in 1909.

Many Albanians had participated in the revolution led by the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) known as the Young Turks, against the Sultanate in 1908. The CUP fought to strengthen and modernize the Ottoman Empire along western constitutional lines, including equality of all races, but opposed any thoroughgoing social and economic transformation, being content with the reinstatement of parliament. The CUP formed a cabinet following the revolution.

Before long, Albanians were accusing the CUP administration of chauvinism, pan-Islamic intrigues in the government, and the Turkish army was carrying out atrocities against Albanians and interfering in politics. The Turkish rulers had little respect for the customs of Albanians and denied them the right to use their language or to build schools.

In April 1912 the CUP manipulated the election results, preventing the return of Albanian deputies. Kosovo Albanians stormed an arms depot in Djakova and soon controlled the whole vilayet. To the north and south of Albania hostilities broke out and within weeks, a number of Albanian troops in the Ottoman army garrisons mutinied and joined the uprising. The Istanbul government resigned and the new administration vowed to address Albanian grievances, but they dragged their feet.

From May to July 1912 there were uprisings in Kosovo and on 9 August Albanian rebel leaders in the north advanced new proposals for reforms that included an autonomous system of justice and administration, new schools, development of Albanian trade, public works and agriculture, amnesty for captured rebels and the court-martial of Istanbul ministers who sought to suppress the Albanian revolt.

The revolt ended on 4 September 1912 when all proposals were accepted except the court-martial of ministers. The uprising preceded the First Balkan War, which broke out in October 1912.