This Week in History provides brief synopses of important historical events whose anniversaries fall this week.

25 Years Ago | 50 Years Ago | 75 Years Ago | 100 Years Ago

25 years ago: Striking Chicago teachers reject latest proposal

Striking Chicago teachers

Striking Chicago teachersOn September 21, 1987, striking Chicago teachers rejected the latest offer presented by the school board. The offer included a one-time bonus of 0.8 percent while strikers were demanding a 10 percent pay increase the first year and 5 percent the second year.

The board’s original offer to teachers amounted to a cut in pay. It included shortening the school year by three days and cutting two paid strike days. The offer of September 20 restored those days, but was paid for by the savings the board accrued by not paying wages for the nine days the strike had gone on.

At the outset, Chicago School Board President Frank Gardner described the teachers’ demands “not even worth contemplating.” The strike, which began on September 8, lasted 19 school days. It involved 28,000 teachers and affected 430,000 students.

Teachers also were angered at School Superintendent Manford Byrd’s announcement that free hot lunches would be served at 20 schools during the strike. The Chicago Teachers Union (CTU) union called it “an outrageous union-busting tactic,” adding, “The only reason they are doing this is to use little children as strike breakers.” The union threatened to picket any school distributing lunches.

In response to the rejection by the teachers, Mayor Harold Washington discussed further strikebreaking preparations, including opening some administration-run schools in the city.

The strike was eventually settled with the teachers receiving a 4 percent pay increase the first year and contingent increase the next. Class sizes would be reduced in some schools. That same fall teachers conducted 20 other strikes in four other states.

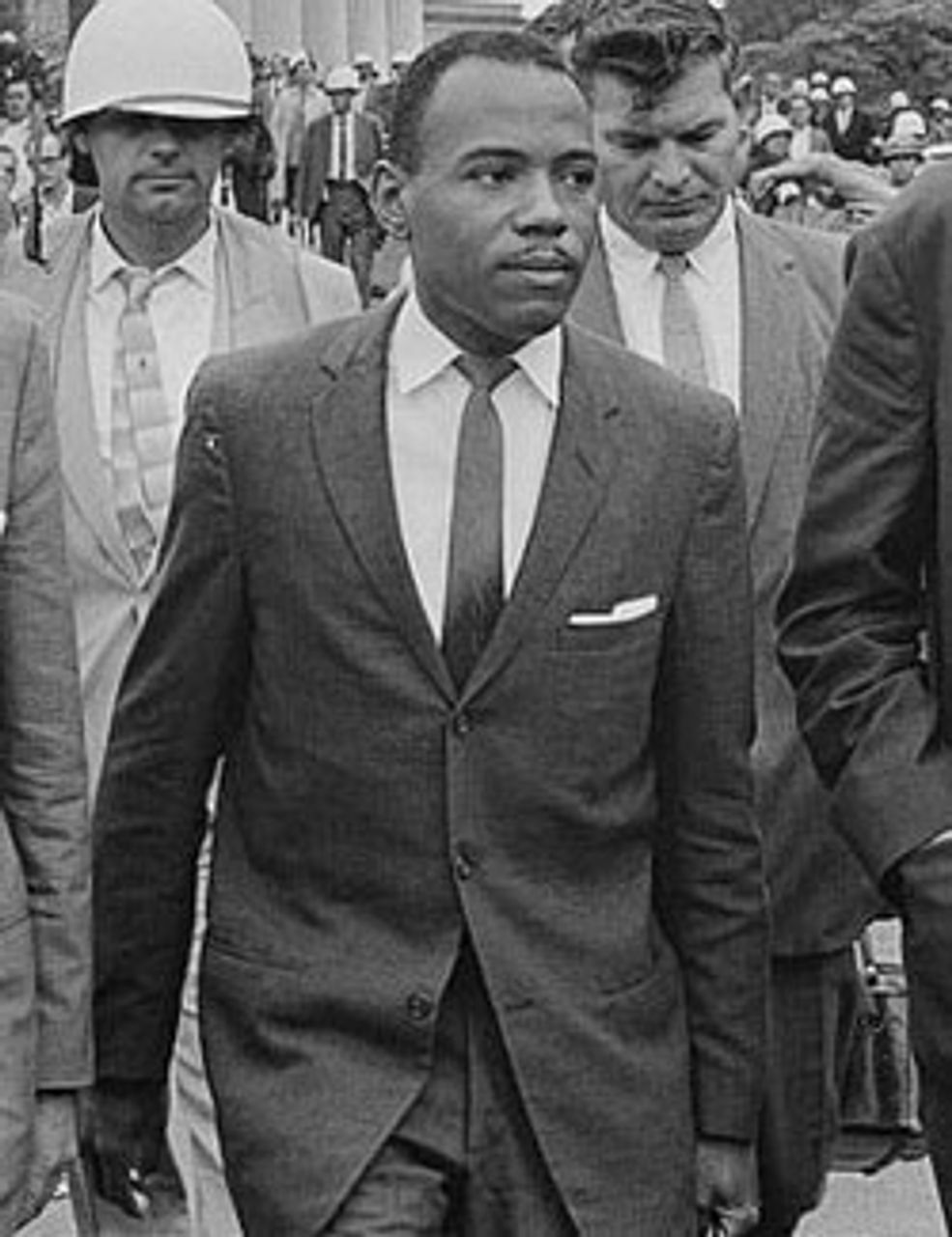

50 years ago: Mississippi governor blocks black student from registering for college

James Meredith

James MeredithOn September 20, 1962, Mississippi’s Democratic governor, Ross Barnett, personally blocked African American student James Meredith from enrolling for college classes at the all-white University of Mississippi, in Oxford. Federal courts had ruled that the school must allow Meredith to attend.

Barnett, a segregationist Democrat, had had himself appointed a special registrar so that he could block Meredith from enrolling. After a 20-minute meeting with Meredith, Barnett appeared before a cheering crowd on campus to announce the young man would not attend “Ole Miss,” as the school is often called. Thousands of students jeered Meredith as he was driven away under the protection of a federal marshal.

Meredith’s eventual enrollment a month later, after Attorney General Robert Kennedy intervened with Barnett behind the scenes, would result in riots in Oxford and the still-unexplained, execution-style killings of two men, one a French journalist, Paul Guihard.

Barnett’s actions, and the violence and extreme racism of the Southern elite, posed “grave problems of international significance for the Kennedy administration,” as the New York Times put it. All over the world—Asia, Latin America, the Middle East, and Africa—the United States was vying for influence with the Soviet Union. The Kennedy administration’s attempt to posture as the advocate of “freedom” was undermined the institutionalized racism of the American South, with images of governors blocking students from attending class, churches being bombed, and dogs attacking children.

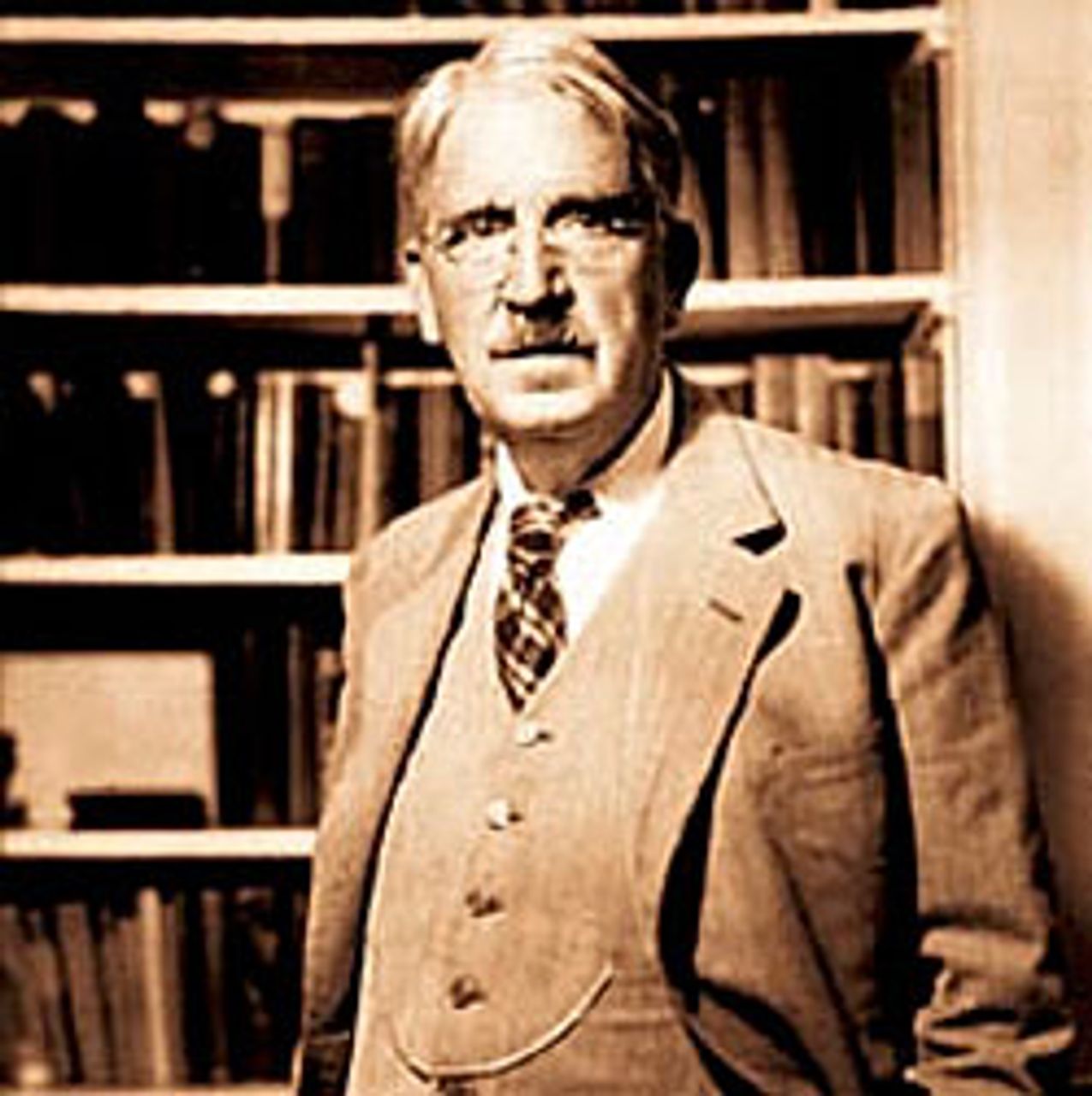

75 years ago: Dewey Commission declares Trotsky innocent

John Dewey

John DeweyOn September 21, 1937, the Dewey Commission, otherwise known as the “Commission of Inquiry into the charges made against Leon Trotsky in the Moscow Trials,” made their findings public in New York City. The commission, led by the eminent American philosopher and educational reformer John Dewey, declared Trotsky and his son Leon Sedov innocent of all charges made against them at the Moscow Trials. The verdict vindicated Trotsky, who had characterized the Moscow Trials as “the greatest frame-up in history.”

The communiqué of the commission declared, “On the basis of all the evidence …we find that the [Moscow] trials of August 1936 and January 1937 were frame-ups …we find Leon Trotsky and Leon Sedov not guilty.” The damning verdict upon the Stalinist show trials concluded that “the conduct of the Moscow trials was such as to convince any unprejudiced person that no effort was made to ascertain the truth.” Trotsky and his wife Natalya, still residing in exile in Coyoacan a suburb of Mexico City, would receive news of the commission’s verdict with joy.

The commission asserted that the Moscow Trials in their entirety, including the improbable confessions made by old Bolsheviks, and especially the charges directed against the co-leader of the Russian Revolution and his eldest son Leon Sedov, were nothing short of calumny.

The commission found Trotsky not guilty of colluding to destroy the Soviet Union, nor did they find any evidence whatsoever that he plotted to restore capitalism to the first workers state. The complete commission’s findings would subsequently be published as a 422-page book entitled Not Guilty! The report of the commission of inquiry into the charges made against Leon Trotsky in the Moscow Trials.

Prior to the inquiry Dewey had stated that the stakes involved in the frame-up of the Trotsky’s ranked alongside those of the injustices of the Dreyfus affair and the case against Sacco and Vanzetti. After the preliminary commission hearing, Dewey returned to the United States and cancelled his European vacation in order to direct the work of the full commission in New York. There was still much to do and further testimony and documentation to gather, not least from the parallel commission of inquiry held in Paris.

The commission members were Dewey; secretary Suzanne LaFollette, a liberal journalist; Benjamin Stolberg, a labor journalist; Otto Ruhle, a former Communist member of the German Reichstag and biographer of Karl Marx; Wendelin Thomas, former Communist deputy in the German Reichstag; Alfred Rosmer, former member of the French Communist Party and editor of newspaper L’Humanite; John R. Chamberlain, a former literary critic of the New York Times; Carlo Tresca, an Italian-American syndicalist; Edward Alsworth Ross, a professor of sociology; and the Mexican journalist Francisco Zamora.

100 years ago: Italo-Turkish battle at Derna

Italian troops in Tripoli

Italian troops in TripoliOn 17 September 1912, Italian and Turkish forces fought each other in the battle of Derna, in north Africa, in one of the bloodiest engagements in the Italo-Turkish war. One thousand Turkish soldiers were killed and another thousand injured, while Italian casualties numbered 61, and 131 injured.

The battle began one hundred and forty miles northeast of Benghazi, near Derna on the Mediterranean coast, when Turkish and Arab fighters attacked the Italian lines. The battle raged for four hours but the poorly armed Arab and Turkish fighters were no match for the superior artillery of the well-armed Italian force.

Three days earlier, on September 14, Italian troops attempted to disband a camp of Arab and Turkish soldiers near Derna. The Italians had occupied a plateau and interrupted supply lines to Turkish troops. Led by commander Enver Bey, Turkish troops attacked the Italians’ position on the plateau but the Italians drove them back.

The Italo-Turko war had begun in September 1911. Italian imperialism intended to take advantage of the decline of the Ottoman Empire by annexing Ottoman territory in modern-day Libya. Italy calculated that if it did not seize Libya, another great power would pre-empt her. All the minor powers in the Balkans—Montenegro, Greece, Bulgaria and Serbia— were rebelling against Ottoman dominance, and seeking to seize Ottoman territory in Europe.

Italian forces carried out brutal repression against Turkish and Arab rebels, including public hangings, in an attempt to intimidate the entire population. The Italians significantly outnumbered their opponents numerically and possessed superior military technology, the war featuring the first use of aerial bombing in a conflict.

The rumblings of the first Balkans war in early October threatened the very existence of the Ottoman Empire, precipitating the Ottomans to sign a treaty ending the Italo-Turkish war, on terms favorable to Italian imperialism.