Wolfgang Brenner: Hubert im Wunderland. Vom Saargebiet ins rote Moskau, Conte Verlag, Saarbrücken 2012

[Hubert in Wonderland: From the Saar region to Red Moscow by Wolfgang Brenner]

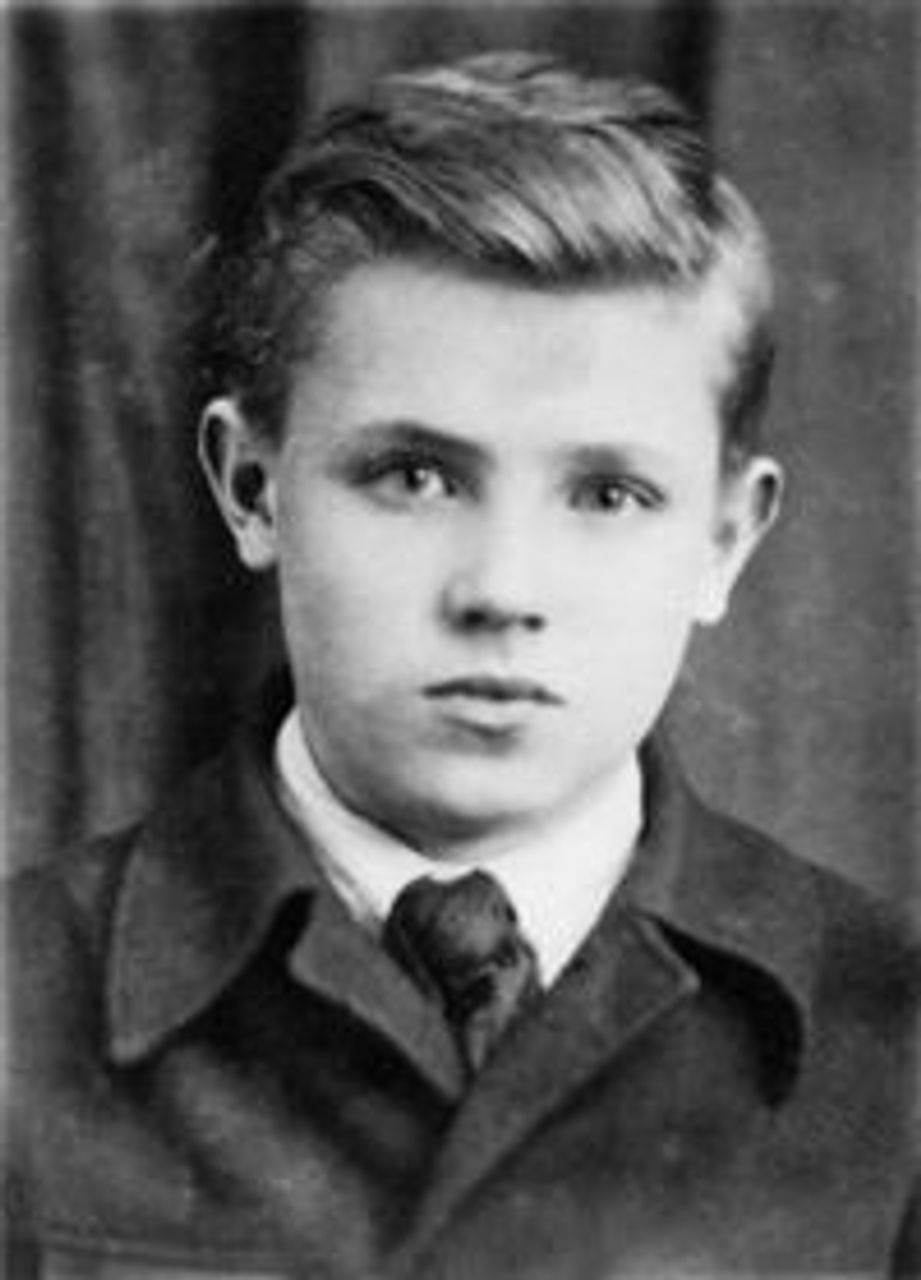

Hubert L'Hoste as a child

Hubert L'Hoste as a childConte Verlag in the German state of Saarland has recently published a remarkable book. Despite the fairy-tale title, Hubert in Wonderland is not a work of fiction. Rather, author and screenwriter Wolfgang Brenner has produced the well-documented story of a boy from the small village of Oberlinxweiler in Germany’s Saar region, who travels to Moscow at the age of ten in late 1933.

He is destined never again to see his homeland or his family—except for his mother. In 1959 he dies in the Soviet Union at the age of only 35. His tragic life story is closely interwoven with the history of the working class so fatally affected by Nazism and Stalinism in the first half of the twentieth century.

Hubert L´Hoste, son of rail worker and German Communist Party (KPD) official Johann L´Hoste, grew up in Saarland with his four brothers and one sister in poverty. The father’s wages were barely enough to feed the family of eight.

The highly industrialized Saar region was put under British and French rule after World War I and Germany’s defeat. As prescribed by the Treaty of Versailles, the coal and iron industries of the Saar Basin were commercially exploited by France; the mass of the population was reduced to terrible hardship. A referendum on the nationality of the territory—German or French—had been fixed for 1935. The Communist Party decided in 1934 to oppose annexation by the German Reich.

The L'Hoste family

The L'Hoste familyThe L´Hoste family vigorously opposed the incorporation of the Saar region into a Germany dominated by the Nazis. This opened up the father and his older sons to persecution from right-wing and pro-Nazi neighbours. A red flag hung from the half of the two-family house they occupied, with a Nazi flag flying from the other half.

The steel baron, Hermann Röchling, was one of the strongest supporters of annexation to the German Reich. Together with the Christian and sections of the Free Trade Unions, he joined forces with the German Front, which was also strongly supported by the Catholic Church. The German Front conducted a huge campaign for inclusion into the Nazi Reich. Hubert and his brother, Roland, active in the Communist children’s organisation, the Young Pioneers, were cruelly harassed by pastors and conservative teachers.

The family suddenly received a visit from journalist and publisher Mikhail Koltsov, highly respected in the Soviet Union and international Communist circles, and his German companion, writer and journalist Maria Osten, who were researching the situation in the Saar region. Staying with the L´Hoste family, they suggested taking Hubert back with them to the Soviet Union. The idea was that he should get to know the workers’ paradise and set an example as a Young Pioneer. He was also expected to keep a diary so he could report on how well the Soviet people were faring, while the Nazis were spreading fear and misery among the German population.

In face of the worsening political situation, the parents were glad to know that at least one of their children would be able to find safety. Hubert found it difficult to say goodbye to his brother Roland, whom he was never to see again. The latter died of typhoid in a prison in Siegburg, having been arrested by the SS and tortured in several concentration camps. The father also had to survive a long journey through the concentration camps.

Hubert arrived in Moscow towards the end of December 1933. He lived with Maria Osten in Koltsov’s flat in a large building inhabited by numerous prominent figures and situated on the banks of the Moscow River near Gorky Park. After a few weeks, he was allowed to attend the Karl Liebknecht School in Moscow, which was open to many children of foreigners.

Koltsov, who was married to another woman, was only occasionally present. Osten, a busy journalist, was also unable to keep watch over Hubert all the time. But the propagandising of the Young Pioneer showpiece proceeded apace. Meetings were organised with celebrities such as Red cavalry general Budyonny and Marshal Tukhachevsky.

Osten was busily writing a work for adolescents, Hubert in Wonderland: Days and Deeds of a German Pioneer, in which Hubert’s experiences in the Saar and the Soviet Union were recounted. The foreword to the book, published in 1935, was written by the Comintern chairman, Georgi Dimitrov. Following publication of the book, Hubert’s popularity reached its peak.

But his school years and youth passed very erratically and not as smoothly as in Osten’s book. He increasingly rebelled against his role as a model Pioneer. His fame was certainly not appreciated by his classmates, who teased and hassled him whenever the teachers were absent. Often he was left to himself because his foster parents frequently had no time for him.

Osten, who had emigrated to the USSR with her first husband, was the editor of a German-language publication and made friends with many Soviet and German writers and artists. During the Spanish Civil War, she traveled to that country and wrote about the International Brigades. Her articles appeared in Russian under the title Spanish Reports. Ernest Hemingway paints an idealised portrait of her and Koltsov (Karkov) in his novel For Whom the Bell Tolls (1940).

Maria brought back a second foster child with her from Spain, with whom Hubert henceforth had to share the attention already dwindling because of Maria’s demanding work schedule. Hubert suffered homesickness and a longing for his family who were now in France. His enthusiasm for the Soviet Union had long since given way to disillusionment and disappointment. Following his relatively unsuccessful school career, he was able to train and qualify as an electrician, due to influence wielded by Koltsov’s brother, Boris Yefimov, the pro-regime cartoonist.

In Spain Koltsov played a filthy role, acting as an accomplice in the liquidation of opponents of Stalinist policy. In particular, he spread countless lies and horror stories about non-Stalinist fighters in the Civil War to justify their murder. One of those who knew too much, Koltsov was eventually recalled to Moscow, arrested there in 1938, convicted as an alleged “Trotskyist” and executed in 1940.

Koltsov warned Osten about coming back to the USSR, but she failed to follow his advice. She returned to Moscow in an attempt to save Koltsov, having learned in Paris of his arrest. When she tried to enter her own flat, Hubert, now living there with a student girlfriend, would not let her in. His argument was that he wanted nothing to do with the wife of an “enemy of the people.” The attitude of the sixteen-year-old reflected the atmosphere of fear and terror then prevailing in the Soviet Union.

Osten was unable to help Koltsov. She sought assistance from Brecht, but he refused to do anything. When Brecht and his family departed for Vladivostok, they left the writer’s terminally ill lover and collaborator, Margarete Steffin, in Moscow with Maria, who cared for her until her death.

Osten was arrested by the NKVD on June 24, 1941, convicted of spying for Germany and France, and died under “mysterious circumstances,” allegedly in the Gulag. (According to other sources, she was shot in Saratov prison on September 16, 1942.) She was posthumously rehabilitated in 1957.

Many of Hubert’s schoolmates and their parents were also swept up and lost their lives in the wave of terror. And Hubert himself was not spared. When he volunteered for Soviet military service, he was rejected.

Following Hitler’s invasion of the Soviet Union, Hubert was deported to Kazakhstan in 1941, as were many other Germans and people of German descent.

German Communist Party cadres and party leader Walter Ulbricht himself briefly appeared at Hubert’s place of exile, Karaganda, to train émigrés for propaganda work in the POW camps. This led to a dispute concerning Hubert’s work on the collective farm. Ulbricht reprimanded him several times because Hubert’s long trek often caused him to arrive late at meetings in the town. He was denied help even when he was ill.

But that was not the end of his ordeal. Hubert was accused of stealing company property, as well as making abusive statements about Stalin, and was sentenced to five years in a prison camp. When he was allowed to return to his family in 1951, he was a broken man. He became increasingly obsessed with the thought of joining up again with his family in the Saar region.

Hubert tried making contact with prisoners of war, but this only brought him a new arrest and five more years in prison, this time with hardened criminals. On one occasion, they would have assaulted and killed him, had not a guard been on hand to stop the attack.

After his release in 1955, two years after Stalin’s death, he secretly managed to make contact in Moscow with Yefimov, who was able to arrange for the seriously ill Hubert to leave Kazakhstan with his family and move to the Crimea. However, he was denied permission to return to Germany. The world was in the grip of the Cold War. No opportunity was to be given to anti-communist West German politicians to exploit Hubert’s suffering for propaganda purposes.

Arrangements were made for Hubert’s mother to visit him in the Crimea. Maria L´Hoste, who was again living in Saarland with her son Kurt, a Dachau concentration camp survivor, was thus allowed to see her son again for the first time in 25 years.

After her departure, Hubert continued trying to get out of the Soviet Union. His marriage broke under the heavy stress. He devised a plan to escape by boat across the Black Sea, but after suffering a ruptured appendix, he died in the summer of 1959. He was buried in a small cemetery in Malorechenskoye and given an obelisk bearing the Soviet star as a gravestone.

Brenner recounts this sad, grim history with great sensitivity. The author strives to place the different stages of Hubert’s life story in some political and historical context, but in this he is only partially successful. This stems mainly from his lack of adequate understanding of Stalinism and other forces that shaped events in Germany and the Soviet Union. He considers the events largely from the limited perspective of his protagonist, who becomes a passive victim of the wheel of fortune, incapable of understanding his fate or doing anything about it.

Brenner fails to examine critically the policies of the German Communist Party (KPD) under Stalin’s disastrous influence, at the time when Johann L´Hoste was among its leading activists in the Saar region and Hubert joined the Young Pioneers.

The German fascists’ coming to power was a direct result of the calamitous policies of the KPD, which opposed a united front with the Social Democratic Party (SPD) against Hitler, although the parties combined had far more support than the Nazis. The KPD hid its cowardly and impotent policies behind fatalistic slogans (e.g., “After Hitler, then us”) and ultra-left attacks on the SPD, which it abused as “social fascist” and a twin party to the Nazis. It relentlessly persecuted the Trotskyists, who advocated a united front against Hitler.

The attitude of the KPD to the Saar question was also characterised by the same mix of passive fatalism and ultra-left phrases.[1] Although Hitler had been in power since January, 1933 and the KPD was banned in Germany, the Stalinists in the Saar region continued calling for annexation to the Third Reich for another year and a half. They tried to gloss over this policy by adopting the radical slogan “The red Saar in a red Soviet Germany.” The KPD only changed its position in August 1934, but by this time it had already demoralised many of its members and supporters, thus contributing to the majority of Saar voters’ support for annexation in 1935.

Brenner does mention some of the Stalinist crimes, but he utterly fails to understand the significance of the Spanish Civil War. Otherwise, he would not have regarded it as an “absurd war” and written: “You would have to be fairly deep into ideology to understand why young people risked their lives for a relatively unimportant political tussle, why fathers and mothers left their children in the lurch to defeat the forces of evil in Barcelona, in Madrid or on the battlefields of Catalonia.”

The struggle of the Left Opposition, about which excellent biographical testimonies are available[2], is not mentioned in Brenner’s book. Therefore, the purges and executions of the Old Bolsheviks and countless other innocent people appear to be the inevitable workings of fate, rather than the result of the counterrevolution of a privileged bureaucracy against the gains of the October Revolution and the international working class. This also applies to Hubert. He was a victim of Stalinism who was unable to oppose it because he—like countless other Communists—was cut off from a political alternative to the terror regime, through no fault of his own.

Nevertheless, Brenner’s book is a very readable biography that provides insight, above all, into some of the most traumatic experiences of the twentieth century and the devastating impact of Stalinism.

Notes

[1] A fairly good account of this can be found in a book by Karl Retzlaw: Spartacus: Aufstieg und Niedergang eines Parteiarbeiters [Rise and Decline of a Party Worker], Frankfurt 1976

[2] Examples of this are the autobiographies of the wife and the daughter of Adolf Joffe—Maria Joffe: One Long Night, London 1977, and Nadezhda Joffe: Back in Time: My Life, My Fate, My Epoch, Michigan 1995.