This Week in History provides brief synopses of important historical events whose anniversaries fall this week.

25 Years Ago | 50 Years Ago | 75 Years Ago | 100 Years Ago

25 years ago: South Africa proscribes anti-apartheid activity

A mass demonstration in South Africa

A mass demonstration in South AfricaThe South African apartheid regime outlawed the 2.5 million-member United Democratic Front, along with 16 other anti-apartheid organizations on February 24, 1988. During the then-20-month-old state of emergency declared by the government of P.W. Botha, the new decree prohibited the organizations from “carrying on or performing any acts whatsoever.”

The 800,000-member Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) was subject to separate restrictions, forbidding it from campaigning for sanctions against the regime, from calling for the release of detainees, from demanding the legalization of outlawed political organizations (such as the African National Congress, or ANC), and from calling strikes.

Other organizations affected included the Soweto Civic Organization, which had led a 20-month-old rent strike, the Detainees Parents Support Committee, which had campaigned to defend those arrested under the state of emergency, the Azanian People’s Organization, and the Release Mandela Committee.

Anglican Archbishop Desmond Tutu, a prominent Nobel Prize-winning South African black reformist leader, said of the developments, “Peaceful pat hs to change are being closed off one by one and those wanting real change are being encouraged by the government’s actions to turn to violence. White South Africans must realize that they are at the crossroads.” He added that if there was no change in policy, “God help us.”

50 years ago: Senate panel warns on Vietnam

Sen. Mansfield

Sen. MansfieldOn February 24, 1963, a US Senate panel warned that Washington’s military and financial effort to maintain the pro-western South Vietnamese regime was becoming an “American war” that could no longer be justified by Washington’s purported national security interests in the region.

The four-member panel, headed by Senate Majority leader Mike Mansfield, a Montana Democrat, called for a “thorough reassessment of our overall security requirements on the Southeast Asian mainland.” It warned that “pursuit of [the present] course could involve an expenditure of American lives and resources which would bear little resemblance to the interests of the United States, or, indeed, to the interests of the people of Vietnam.”

The panel, which had been called for by US President John Kennedy to investigate and report to the US Senate Foreign Relations Committee on US involvement in Southeast Asia, also questioned whether the $5 billion spent on Southeast Asia since 1950 and the more than 50 US lives lost since 1955 had achieved worthwhile results. “[S]ubstantially the same difficulties remain,” said Mansfield, “if, indeed, they have not been compounded.”

Yet the report to Senate Foreign Relations Committee Chair William Fulbright stopped short of calling for a reversal of Kennedy’s escalation. It did not challenge the executive “police action” authority wielded by presidents Truman, Eisenhower, and Kennedy that had led to the presence of 10,000 US troops in Vietnam by 1963. The US was in fact engaged in an undeclared war against the nationalist forces of the National Liberation Front, which sought land reform in the south and reunification with the North Vietnam of Ho Chi Minh. The report warned of “meat axe” cuts in funding for South Vietnam, which might “lay open the region to massive chaos.” It concluded that even in “the best of circumstances outside aid in very substantial size will be necessary for very many years.”

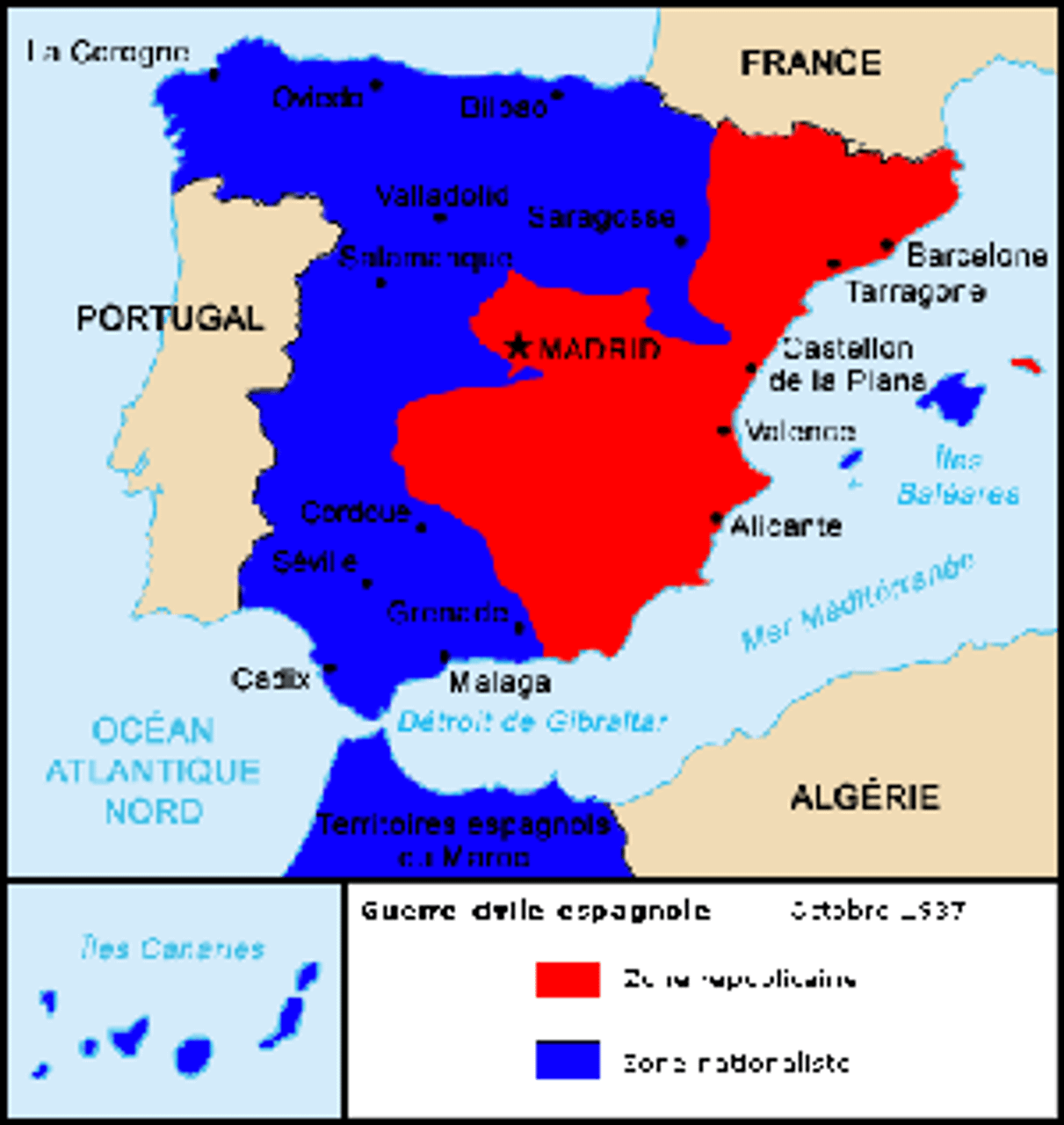

75 years ago: Teruel falls for the last time to Franco’s forces

Spain before Battle of Teruel

Spain before Battle of TeruelAfter a protracted and bitter fight, waged in the coldest Spanish winter for twenty years, the town of Teruel in Aragon fell once again to General Franco’s fascist forces on February 22, 1938. According to the London Times correspondent the Nationalist flag flew over the ruins of the military headquarters in the Plaza del Torico, and Te Deum was sung in the ruined cathedral in celebration.

At noon the following day some thirty Nationalist bomber planes flew over Teruel on their way to attack the retreating Republican forces. Franco’s forces would soon rapidly sweep through the rest of Aragon.

The fascist assault began on February 17. Within three days Franco had the town encircled and Republican soldiers began surrendering in droves. The Republican army had taken the town from fascist control only six weeks previous. Both sides lost a total of approximately 140,000 men in the three months between December 1937 and February 1938, many dying from exposure.

Some 15,000 prisoners were taken when the town fell, and these like most Republican prisoners—apart from those identified as socialists who were shot or imprisoned—were then subsequently drafted into Franco’s army. Vast quantities of guns, ammunitions, and material were captured. Together with the fall of the Republican northern front in late 1937, the loss of Teruel meant that the Republic had to call up ever younger and insufficiently trained men to fight at the front.

100 years ago: Mexican president assassinated

Francisco Madero

Francisco MaderoOn February 18, 1913, Mexican president Francisco Madero and Vice-president José Pino Suárez were arrested by federal troops. Madero had led an insurrection against the dictatorial regime of Porfirio Diaz, sparking the Mexican Revolution in 1910. He became president in 1911.

Unable to make the modest reforms that he had promised such as redistribution of land, Madero’s popularity plunged. His regime was soon beset by revolts from peasant leaders seeking social and land reforms and from generals who served under Diaz.

The United States, which controlled vital resources in Mexico including mining and oil, was concerned that under these pressures, Madero would undermine US interests. US Ambassador Henry Lane Wilson initiated discussions with General Victoriano Huerta, commander of the army under Madero, and General Felix Diaz, nephew of the former president. Wilson promised Huerta Washington’s support for “any government capable of establishing peace and order in place of the government of Señor Madero.” Mexico City became a battleground as troops loyal to Madero fought the conspirators.

Ambassador Wilson visited Madero on February 11, 1913, and expressed support for Diaz, threatening to send US warships against Madero. Madero’s government was informed the following day that 4,000 US soldiers were due to arrive in Mexico to establish order if Madero did not resign.

On February 16, Wilson boycotted the ceasefire he had initiated while maintaining contact with Diaz and Huerta, conspiring with coup forces. Madero was arrested at 1:30 pm the next day by Huerta’s troops, and his brother Gustavo was detained and tortured to death. Wilson convened the diplomatic corps where a vote of confidence for Huerta and the army was proposed. Huerta and Diaz then met with Wilson to discuss the distribution of power. Wilson advised Diaz’s aides to support Huerta as interim president or “true war” would be unleashed.

On February 21, Wilson instructed all US consuls to promote support for the Huerta government. The next day Madero and Suárez were executed against the prison wall by a provincial corporal and a federal army member. Huerta declared himself president.