This Week in History provides brief synopses of important historical events whose anniversaries fall this week.

25 Years Ago | 50 Years Ago | 75 Years Ago | 100 Years Ago

25 years ago: Jordan’s King Hussein relinquishes claim to West Bank

Jordan and the West Bank

Jordan and the West BankIn a July 31, 1988 declaration, King Hussein of Jordan renounced all claims of the country over the Israeli-occupied West Bank. This followed two measures taken in the previous two days: the cancellation of a $1.3 billion development program for the West Bank and the dissolution of the lower house of the Jordanian parliament, half of whose members represented West Bank districts.

This maneuver was a reaction to the ongoing Intifada, the eight-month-long revolt of mainly young Palestinians in the occupied territories of Gaza and the West Bank against the miserable conditions imposed on them by the Zionist regime. Hussein’s handing over control of the region to the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) fit smoothly with the strategy of both Israel and US imperialism to increase pressure on the PLO to quell the revolt. Moreover, a complete separation from Jordan threatened to destroy the economy of the West Bank.

The Jordanian monarchy ruled the West Bank from 1948 until 1967 when Israel occupied it in the Six-Day War. The whole economic base, along with much of the legal superstructure of the territory, remained closely linked to Jordan, despite the Israeli occupation. Many West Bank teachers were paid directly from Amman. Doctors, lawyers, pharmacists, engineers and other professionals received their licenses from the Hussein monarchy as well. West Bank residents used Jordanian passports, students received Jordanian diplomas and Jordanian currency circulated in the area. Most Palestinians did business at one of the branches of Jordan’s Cairo-Amman Bank and Jordan paid the salaries of 18,000 civil servants.

King Hussein’s decision would lead to an economic catastrophe in the West Bank and eventually a rapprochement with Israel, ending the official state of war existing between Israel and Jordan since 1948.

50 years ago: South Vietnamese regime in crisis

Self-immolation of Thich Quang Duc

Self-immolation of Thich Quang Duc[Photo: Malcolm Browne]

The South Vietnamese government was thrown into deep crisis this week in 1963 by mounting protests among Buddhists against the US puppet regime of Ngo Dinh Diem. The deeply unpopular government was prosecuting a war, funded by the US and increasingly assisted by American soldiers, against the National Liberation Front (NLF). The NLF sought nationalization of the land and industry and reunification with North Vietnam.

On July 30, tens of thousands of Vietnamese marched in cities throughout South Vietnam in a memorial demonstration for Thich Quang Duc, a Buddhist priest who had burned himself to death in protest against Diem’s religious policies on June 11. In a country that was more than 70 percent Buddhist, the government and military were dominated by a narrow Roman Catholic elite, which owed its privileges to the long period of French colonial rule.

On August 3, Mrs. Ngo Dinh Nhu, sister-in-law to Diem and effectively South Vietnam’s First Lady, inflamed tensions by accusing Buddhist monks of committing treason, murder, and “Communist tactics.” The New York Times reported that the US embassy, which had been seeking to improve Diem’s image, “was not happy with the speech.” The Times added that Nhu was “widely considered one of the three or four most powerful figures in South Vietnam, which is basically ruled by the Roman Catholic Ngo family.” Her husband and the brother of the president, Ngo Dinh Nhu, who dominated the military and secret services, warned the same day of a right-wing coup d’etat that would “crush” the Buddhists.

On August 4 another priest, this time in the coastal city of Phanthiet, burned himself in protest against the government. The government removed the body, thereby denying a Buddhist service and further inflaming tensions.

Henry Cabot Lodge was confirmed as ambassador to South Vietnam by the US Senate on July 31, replacing Frederick Nolting. Lodge, a member of one of the leading US political families, had been the Republican vice presidential candidate on the Nixon ticket in the 1960 elections, losing to the Kennedy-Johnson ticket. Nolting had been an outspoken supporter of the Diem regime. Lodge would quickly arrive at a very different position, concluding that Diem had to be removed.

75 years ago: British inquiry into partition of Palestine draws to close

British soldiers search Palestinians

British soldiers search PalestiniansOn August 3, 1938, three months after arriving in colonial Palestine to collect information on the technical aspects of dividing the territory into three parts, the Palestine Partition Commission finished its research. The British panel headed by Sir John Woodhead would subsequently prepare their final report and submit it to the government.

The borders of colonial Palestine were established after the defeat of the Ottoman Empire during the First World War by British and French imperialism. The victorious European powers carved up the territories formerly controlled from Istanbul. The mandate for Palestine incorporated the Zionist program, embracing the Balfour Declaration of 1917, which detailed the establishment of a Jewish national home. Article 2, for instance, stated that the mandatory should establish “such political, administrative and economic conditions as will secure the establishment of the Jewish national home.”

At the end of hostilities in 1918 the Jewish population of the territory was approximately 70,000. By 1936, after encouragement by Zionist organizations and the mandated British administration, persecution in Eastern European, especially Poland, and the rise of German fascism, immigration swelled the Jewish population of Palestine to just over 400,000.

The British commission of inquiry had previously concluded that the causes of the mounting strife between Arabs and Jews were the Arab population’s desire for independence and rejection of Zionism. The verdict of the commission was that the mandate was unworkable because reconciliation between the two communities was impossible. It recommended partition of the land into two separate and ethnically homogeneous states—a plan that would necessarily require large-scale transfers of people who were living in the “wrong” state.

The commission arrived in Palestine amidst a smoldering civil conflict between Arabs and Jews. During the intervening three months this exploded into the worst inter-ethnic conflict since British occupation began in 1917. Both sides committed barbaric outrages.

The one-sided character of the “technical” commission was evident from the outset. It heard from a gamut of pro-Zionists, including rabbis, Christian ministers, Anglican bishops and archdeacons, in addition to the opinions of officers from the administration, heads and experts from all government departments, especially the police.

However, not one Arab appeared before the commission. The Emir Abdullah was allowed to submit a memorandum proposing an alternative to partition, which was nevertheless not accepted by the commission because they claimed it lay outside their terms of reference.

100 years ago: Wheatland Hop Riot in California

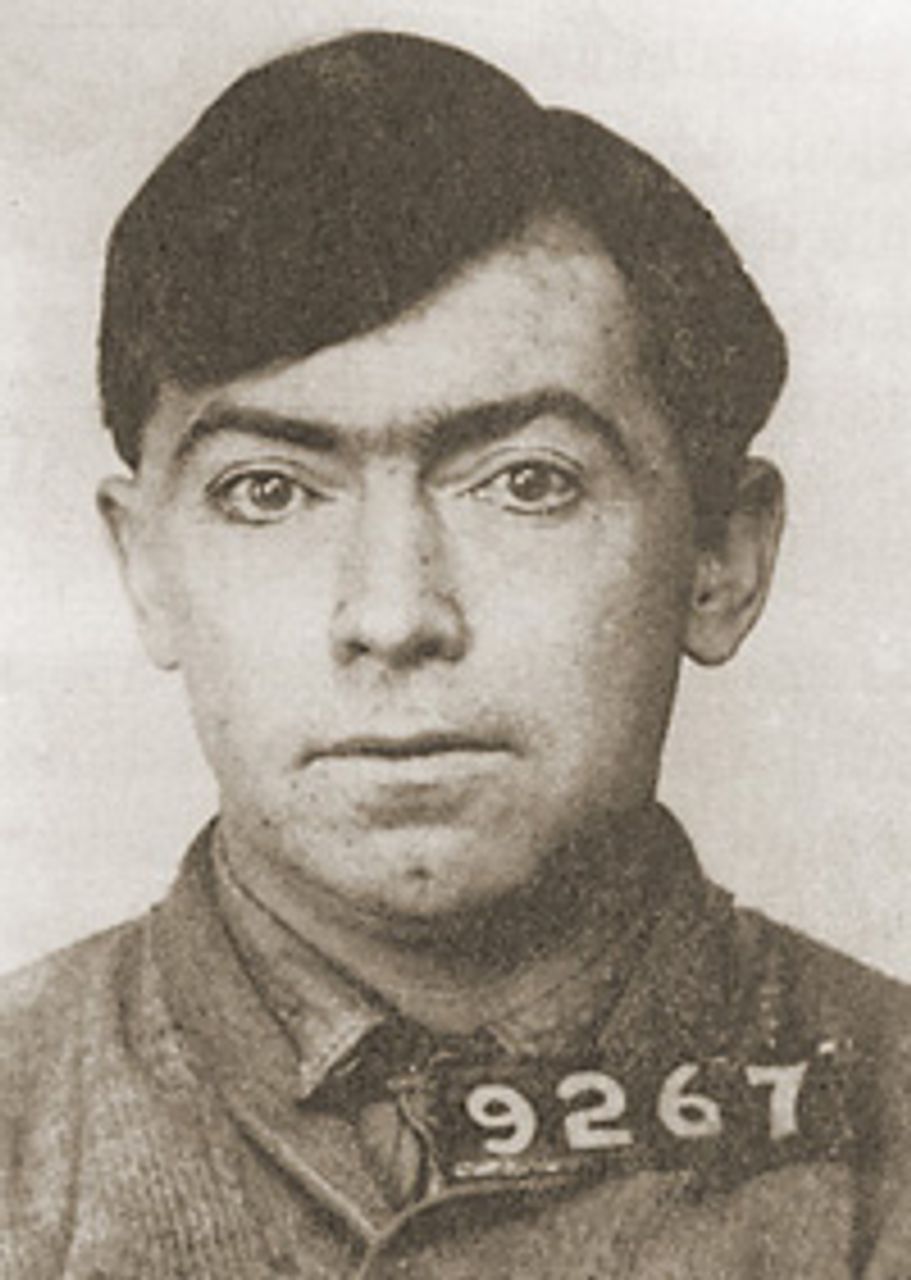

Richard "Blackie" Ford

Richard "Blackie" FordOn August 3, 1913, tensions between impoverished farm workers in Northern California and local authorities boiled over when a local sheriff and his deputies attempted to disperse a mass meeting of agricultural laborers at the Durst ranch in Wheatland. Four people, including the Yuba County district attorney, a deputy sheriff, and two workers were killed in the violent confrontation that ensued. The incident, dubbed the “Wheatland Hop Riot,” marked the beginning of a series of intense social struggles in the Californian agricultural sector.

The Durst Ranch, owned by Ralph H. Durst, was the largest employer of seasonal agricultural laborers in California. Durst had recently advertised for new workers, promising relatively high pay and plentiful work. Nearly 3,000 workers responded, only to find on arriving at the ranch that just 1,500 laborers were required a day, and that pay rates were lower than advertised. Workers and their families were housed in overcrowded tents, endured unhygienic toilet facilities and a dearth of clean water. On average, workers were paid $1.50 a day for 12 hours labor.

Some workers had ties to the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), which called for the establishment of “one big union” and advocated a revolutionary syndicalist struggle against the profit system. On August 1, around 30 workers, with Richard “Blackie” Ford as their spokesman, established a local of the radical organization. They issued Durst with demands for decent pay and conditions, and threatened strike action if they were not met. Durst responded by unsuccessfully attempting to have the leaders of the group arrested. Mass meetings of laborers were organized, addressed by Ford, and Herman Suhr, another figure in the IWW.

On August 3, local authorities summoned by Durst attempted to disperse a mass meeting, firing shots into the air. Workers responded to the attack with anger, with some reportedly seizing the guns of the authorities, and shooting. In addition to four deaths, numerous people were injured, and 100 workers were arrested. Troops from the state militia were deployed.

Ford and Durst were charged and found guilty of second-degree murder and sentenced to life in prison by a rigged jury for leading the struggle, though no clear connection between them and the deaths could be established. In spite of the repression the struggle greatly enhanced the stature of the IWW among agricultural workers in California and the American West, many of whom were impoverished migrants, a layer of workers ignored by the AFL craft unions.