This Week in History provides brief synopses of important historical events whose anniversaries fall this week.

25 Years Ago | 50 Years Ago | 75 Years Ago | 100 Years Ago

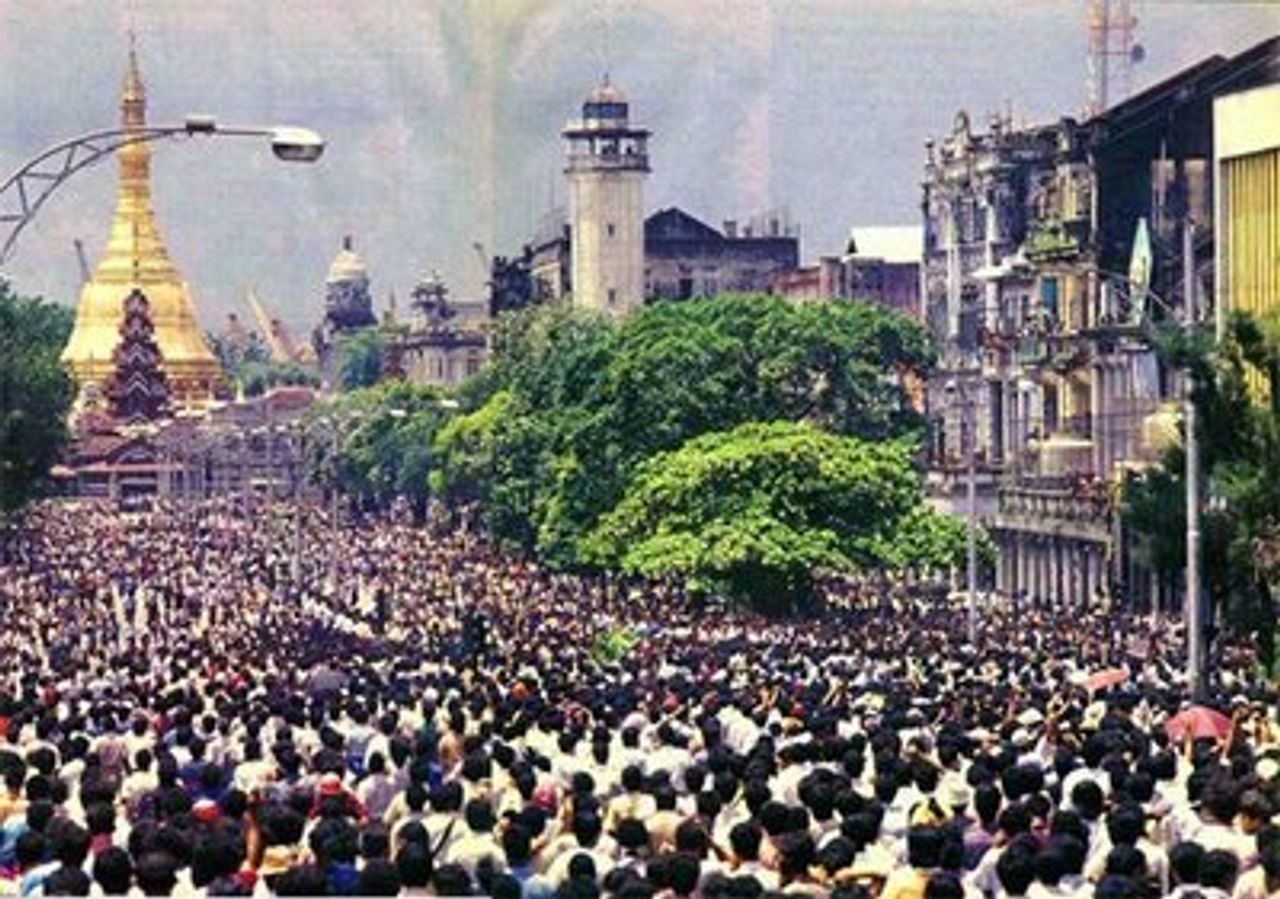

25 years ago: Massive demonstrations rock Burma

Only two weeks after the resignation of Burma’s military strongman, the so-called “8888 Uprising” brought masses into the streets on August 8, 1988. Over the next several days, Yangon (then Burma’s capital, now known as Rangoon) witnessed massive demonstrations confronting the armed forces. Students initially organized the actions in the capital, but protests and general strikes spread throughout the country, including rural areas, bringing out hundreds of thousands of youth, wrkers, and farmers in defiance of the police-state regime.

Demonstrators, carrying red banners, tore up railroads, set fire to police stations, other official buildings and vehicles. When the armed forces started shooting, demonstrators raided police stations and returned fire. They rallied again and again in the face of military violence.

Demonstrations in Rangoon

Demonstrations in RangoonThe demonstrations were not confined to the capital. People came onto the streets in most of the main cities. Along with Yangon, Moulmein (now Mawlamyine) was the most seriously affected. In that city, it was reported that people seized weapons from policemen who were shooting at them and then marched into a police station, shooting a policeman dead.

Initially the regime was taken by surprise by the force of the demonstrations. In an attempt to quell the protests, the hated General Sein Lwin resigned as Burma’s president and ruling party leader after serving for just 17 days.

On his announced resignation two weeks earlier, strongman Ne Win warned the public that further demonstrations would face the full force of arms. Although not the official head of state, Ne Win dominated behind-the-scenes, directing state repression against the population. While government figures reported only 100 deaths and hundreds more injured in the protests, deaths likely numbered in the thousands.

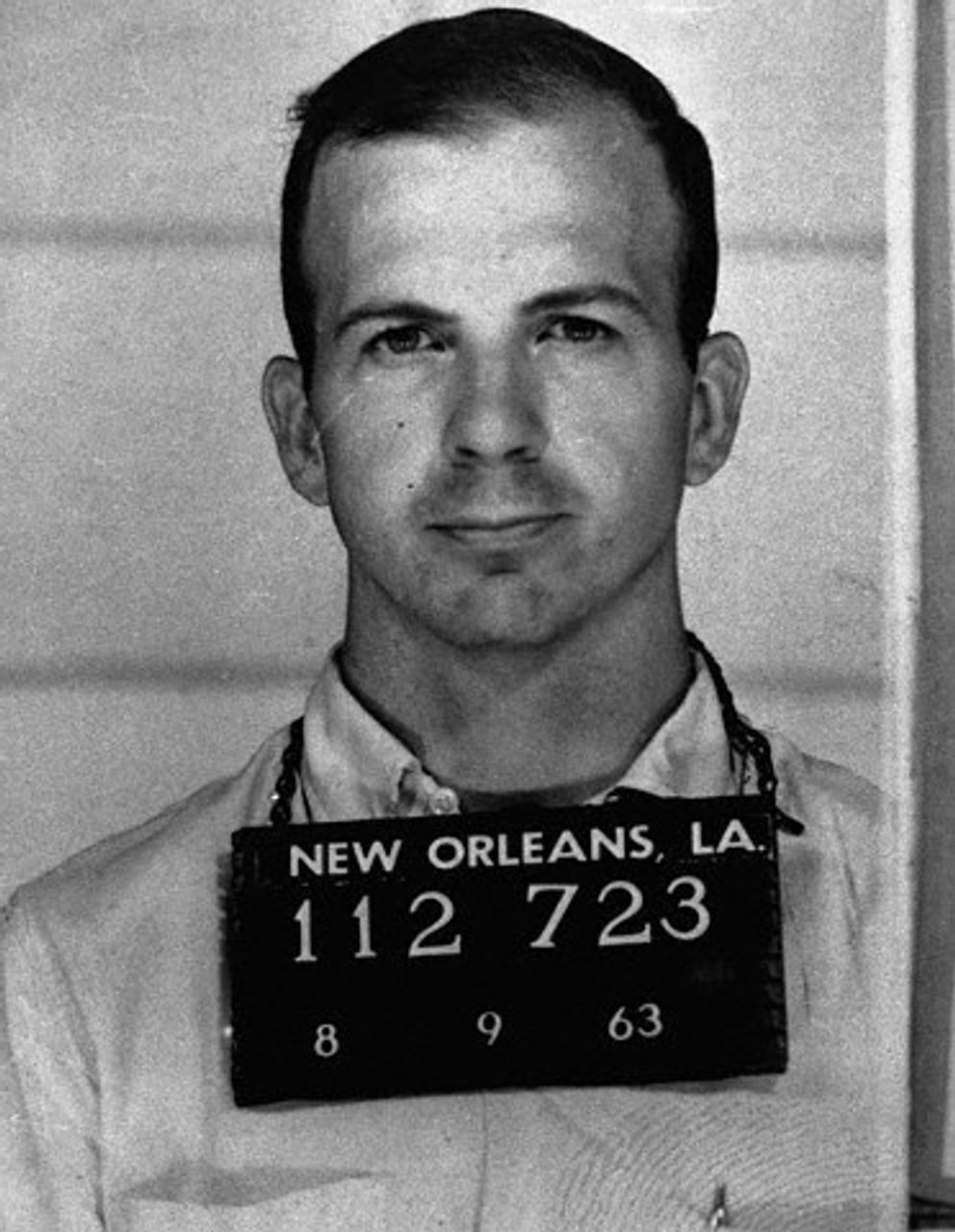

50 years ago: Lee Harvey Oswald arrested in New Orleans

On August 9, 1963, the future assassin of President John F. Kennedy, Lee Harvey Oswald, was arrested in New Orleans. After distributing pro-Castro literature for the Fair Play for Cuba Committee, he had gotten into an altercation with three anti-Castro Cuban émigrés. Booked for disturbing the peace, Oswald spent the night in jail and was released after requesting to speak to an FBI agent.

Lee Harvey Oswald after arrest

Lee Harvey Oswald after arrestOswald, then 23 years old, had a murky past that included connections to US spy agencies and the State Department. A former Marine, Oswald had defected to the Soviet Union in October 1959, but renounced his decision and was financially assisted by the State Department to return to the US in the summer of 1962. While in the Soviet Union he married Marina Nikolayevna Prusakova, and together they settled with their Russian-born daughter in Dallas, Texas, where they befriended the anti-communist Russian émigré George de Mohrenschildt, a prominent oil geologist with close connections to US spy agencies.

Oswald was hired in New Orleans in late April 1963 by the Reilly Coffee Company, whose owner was a supporter of an anti-Castro organization called the Free Cuba Committee. Oswald nonetheless joined the Fair Play for Cuba Committee, a group backed by the US Socialist Workers Party, which advocated a non-interventionist policy in relationship to the Cuban Revolution. Like the SWP, the Fair Play for Cuba Committee was heavily infiltrated by the FBI.

Oswald was the only member of the Fair Play for Cuba Committee in New Orleans and paid for his own office and literature production costs. The building found on the address printed on Oswald’s leaflets also housed a militant anti-Castro group, the Cuban Revolutionary Council, and the offices of Guy Bannister, a former FBI agent. Oswald frequented Bannister’s office, according to the latter’s secretary.

After his arrest Oswald requested an audience with the FBI from local police. Before his release from jail on August 10, Oswald spoke for more than one hour to FBI agent John Quigley.

75 years ago: Hitler clashes with army general staff over Czechoslovakia

In an unorthodox step responding to opposition amongst his army general staff over the prospects of invading Czechoslovakia, German Chancellor Adolf Hitler summoned the second tier of army officers—not the top military leadership—to his residence at the Berghof on August 10, 1938. For several hours he harangued those who might well have expected rapid promotion through the ranks in the event of a military conflict involving Nazi Germany.

When the initial version of “Case Green,” the military plan to invade Czechoslovakia, was issued in May, the document detailed Hitler’s attitude towards the central European state thus: “It is not my intention to smash Czechoslovakia by military action within the immediate future.”

Adolf Hitler

Adolf HitlerHowever, by early June, after the loss of prestige suffered by Germany in Hitler’s eyes when Czechoslovakia had moved some 180,000 troops to the border, a revised “Case Green” was drawn up. This time the preamble contained a more recent quote by Hitler: “It is my unalterable decision to smash Czechoslovakia by military action in the foreseeable future.”

In two memorandums in late May and early June, Army Chief of Staff Ludwig Beck wrote scathingly about what he perceived was Hitler’s blasé attitude towards the strong possibility of French and British intervention should Germany invade Czechoslovakia. Beck attempted to persuade the head of the Fourth Army Group, Walther von Brauchitsch, of what he believed to be Hitler’s folly. However, though he shared some of Beck’s reservations, von Brauchitsch was loathe to appear to challenge or be remotely critical of Hitler’s military plans. Von Brauchitch would not be won over to the idea of any sort of generals’ ultimatum to Hitler.

100 years ago: Treaty of Bucharest concludes Second Balkan War

On August 10, 1913, the Treaty of Bucharest was concluded by Bulgaria, Romania, Serbia and Greece, ending the Second Balkan War. Disgruntled over the distribution of territories taken from the Ottoman Empire in the First Balkan War, Bulgaria had launched an attack on her former allies on June 1913, setting off the Second Balkan War.

The treaty’s terms saw a re-division of the Balkans, with Bulgaria surrendering vast tracts of land to its former allies. Northern and central Macedonia went to Serbia, doubling its territory, and increasing its population by more than 1.5 million. Southern Macedonia, including Epirus, Thessaloniki and Crete, was acquired by Greece. Greece also increased its population to 4,363,000 from a previous 2,660,000. Romania received southern Dobruja.

Signatories of Peace of Bucharest

Signatories of Peace of Bucharest Bulgaria, which had sought control of most of Macedonia, was only granted relatively small portions of that territory. It was also granted Dedeağaç, a strip of 110 km on the Aegean seaboard, now known as Alexandroúpolis. It had to agree to dismantle its fortresses and to build no forts in proscribed areas.

The treaty was an interlude in a region wracked by political instability and did nothing to resolve the underlying conflicts, which were leading inexorably to war. The great Russian Marxist Leon Trotsky wrote that the treaty was “made up of evasions and lies.”

“It provides a worthy crown for a war of greed and light-mindedness,” Trotsky wrote. “But while crowning that war, it does not end it. Suspended owing to utter exhaustion, the war will be resumed as soon as fresh blood is flowing in the arteries … verily the blood of the slain cries out to heaven, for it was shed in vain. Nothing was achieved … nothing settled. The Eastern Question burns still, discharging poison like a frightful ulcer, in the body of capitalist Europe.” Within a year the First World War broke out, sparked by a Serbian nationalist’s assassination of Austria’s Archduke Franz Ferdinand.