We are publishing below a report by David North to public meetings held by the World Socialist Web Site and the International Committee of the Fourth International in Wellington, New Zealand, and Sydney, Australia, on August 29 and September 5 respectively. North is chairman of the WSWS International Editorial Board and national secretary of the SEP in the US.

On November 2, the United States will hold its quadrennial presidential election. For reasons that are not difficult to understand, the outcome of this election is being awaited with intense interest all over the world—indeed, perhaps with greater concern outside the US than within it. There is a sense that the United States is a dangerous country, controlled by ruthless and reckless militarists who will stop at nothing to achieve their global aims. And this is not an opinion with which I would argue.

During the past week, the gathering of the Republicans in New York City to renominate George W. Bush as their presidential candidate bore a greater resemblance to a Nazi Party Day rally in Nuremberg than to the typical convention of a bourgeois-democratic political party in the United States. Outside the convention, on the streets of New York, nearly 2,000 people were swept up and arrested by police in massive dragnets organized to prevent or break up political protests.

Inside the convention, a reactionary mob cheered wildly as they listened to fascist-style speeches delivered by the likes of Vice President Dick Cheney—the once and future bagman for Halliburton who now presides over a secret government about which the American media says nothing—and Senator Zell Miller from Georgia, a Democrat, who speaks for that section of the Democratic Party that is supporting, either openly or covertly, the reelection of George Bush.

It was in Miller’s speech that the anti-democratic, authoritarian, militaristic and imperialistic outlook that is rampant within the ruling elite found its most precise expression. He said that, “It is the soldier, not the reporter, who has given us freedom of the press. It is the soldier, not the poet, who has given us the freedom of speech.” Of course, the media did not call attention to the absurdity of this statement, which is contradicted not only by the legal theory which forms the basis of the US Constitution and its evolution but also by the actual history of the country. Miller’s remarks cannot be dismissed as merely the ravings of a right-wing political lunatic, for the past three years have seen a determined effort by the government to legitimize the use of military tribunals in which civilian defendants are stripped of all constitutional rights, including that of habeas corpus.

This brings me to another statement made by Miller in his address before the Republican Convention:

“No one should dare to even think about being the Commander in Chief of this country if he doesn’t believe with all his heart that our soldiers are liberators abroad and defenders at home.”

This declaration falsifies the content of the US Constitution and the intent of its framers. But Miller’s statement is not in any way original or exceptional. The frequent assertions by politicians and media types that the president is the country’s “commander in chief” is intended to disorient the people, undermine their natural democratic instincts, and legitimize the drift toward a military-police dictatorship.

According to Article II, Section 2, Clause 1 of the US Constitution, “The President shall be Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States, and of the Militia of the several states, when called into the actual service of the United States...” There is nothing ambiguous about this clause: the president is the commander in chief not of the country as a whole, but of the military. He is the country’s principal elected magistrate, not its fuehrer. The correct usage of the president’s auxiliary title underscores the domination of the elected civilian representatives of the people over the military, rather than the military over the civilian branch of government. Miller’s speech is merely one example of the degree to which basic concepts of democracy have become utterly alien to the American ruling class.

We are not dealing with merely a process of intellectual degeneration. The relentless accumulation of wealth in a very small stratum of the American people has the inevitable impact of narrowing the real social base upon which bourgeois rule rests. The ruling class is compelled to create another base, consisting of elements that stand outside of and are to a considerable extent independent of the broad mass of the people. This is the role of the volunteer army, which is supplemented by gangs of contract killers and torturers hired by the military to augment the forces of repression in Iraq and Afghanistan. The experience of urban warfare in Iraq, where American soldiers become accustomed to and, in some cases, even acquire a taste for killing and repressing civilians on a mass scale, is creating a dangerous social type upon which the ruling elite will increasingly depend to maintain “law and order” in the United States.

Some of you may recall that I spoke here in Sydney nearly four years ago, in this hall, in the immediate aftermath of the balloting in the November 2000 election. It was December 3, 2000, and the results of the election were still unknown. I said at the time that the outcome of the election would reveal the extent to which there still existed a commitment to traditional forms of bourgeois democracy in the United States. Less than two weeks later, the Supreme Court intervened to stop the recount of disputed Florida ballots, and selected George W. Bush president of the United States. That event marked a turning point in American history. Its worldwide implications have since become clear.

The events of the last four years have changed profoundly global perceptions of the United States. Even for those who were not inclined to view American society through rose-tinted glasses and knew better than to accept uncritically Washington’s endless professions of its democratic and benevolent ideals, recent developments have come as a shock. The invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq have provided examples of the sort of unbridled imperialism that the world has not witnessed since World War II. The grotesque images of sadism displayed in the photographs taken in Abu Ghraib prison will define for an entire generation the brutal and predatory essence of the American occupation of Iraq.

In politics, as with life in general, people have a natural inclination to hope that simple and easy solutions can be found to difficult and serious problems. Herein lies the appeal of the notion that the election of John Kerry as president of the United States will, if not fundamentally transform, then at least lead to an improvement in the overall international political climate. Those who would like to believe this proceed from the conception that present American policy is to be explained by the personal characteristics of the occupant of the White House. Ironically, this conception transforms Bush, an ignorant nonentity, into something akin to a world historical figure.

But the “Bad Bush Theory of History” can provide no guide to an understanding of, let alone a solution to, the great problems of our day. Even if Kerry were to win this election—despite the cowardly and bankrupt character of his campaign—this would not alter in any significant manner the destructive and barbaric trajectory of American imperialism. It will not bring the occupation of Iraq to an end. It will not lessen the likelihood of further and even more destructive wars in the near future.

Even if one were to grant that the conduct of American foreign policy is shaped to some extent by criminal aspects of the personalities of Bush and his coterie—and it certainly is—this subjective factor is of secondary importance. After all, the very fact that Bush’s policies have enjoyed such broad support within the political and social establishment of the United States demonstrates that factors far more substantial than the personality disorders of the president are involved in the formulation of state policy.

The invasion and occupation of Iraq represents a colossal failure of American democracy. This war was launched, as everyone in the world now knows, on the basis of out-and-out lies: 1) that there existed weapons of mass destruction in Iraq; 2) that the regime of Saddam Hussein was allied to Al Qaeda and, by implication, somehow involved in the events of 9/11; and 3) that the United States was seeking to bring democracy to Iraq.

Prior to the invasion of March 2003, none of these claims was subjected to serious examination by the political establishment or the mass media. The oversight was not an accident. To the extent that the bellicose policies of the Bush administration enjoyed broad support within the ruling elite and both of its major political parties, there was no interest in too searching an examination of the reasons advanced by the government for going to war. This political reality is underscored by the fact that the subsequent exposure of these lies has led to no significant erosion of political support for the continued occupation of Iraq within the ruling elite. The recent declaration of Senator Kerry that he would still have voted for the notorious Senate resolution of October 2002 authorizing the use of force against Iraq, even had he known then that there were no weapons of mass destruction in that country, is a crushing refutation of the argument that the policies of the Bush administration represent some sort of aberrant departure from a more restrained and moderate course of American foreign policy.

In justifying its own policies, the Bush administration endlessly invokes the specter of September 11, 2001. Indeed, in the modern mythology of American politics, that date occupies an exalted place. After 9/11, as the phrase goes, “everything changed.” This is one of those universally accepted truisms that do not bear too careful scrutiny.

The events of 9/11 played no significant role whatever in determining the international strategy of the United States. Any moderately knowledgeable observer of American foreign policy could have anticipated, well before September 11, 2001—indeed, well before the installation of Bush as president in January 2001—that the invasions of both Afghanistan and Iraq by the United States were inevitable.

The entire direction of American foreign policy since the conclusion of the first Gulf War was calculated to justify a resumption of war against Iraq. Similarly, the invasion of Afghanistan was anticipated by the growing preoccupation of American policy makers throughout the 1990s with the geo-strategic and economic significance of Central Asia. It was none other than Zbigniew Brzezinski, the former national security adviser of President Jimmy Carter, who wrote a book in 1997 entitled The Grand Chessboard¸ in which he argued that America’s global position in the twenty-first century depended on achieving a dominant role in Central Asia. Acknowledging the substantial social costs that protracted American military involvement in Central Asia would impose upon the American people, Brzezinski warned that domestic support for such actions would be difficult to achieve “except in conditions of a sudden threat or challenge to the public’s sense of domestic well-being.”

September 11 did not lead to a reformulation of American foreign policy. Rather, it provided a pretext for the realization of geo-strategic ambitions formulated and pursued by US administrations dating all the way back to that of Jimmy Carter.

It is worth restating the essential geo-strategic aims which underlie the wars launched during the Bush administration and, lest this be forgotten, the war launched by President Bill Clinton against Serbia in 1999.

The principal objective of the three presidential administrations (Bush I, Clinton, and Bush II) that have held office since the dissolution of the USSR in 1991 has been to exploit the historic opportunity provided by the Soviet collapse to establish an unchallengeable hegemonic position for the United States in world affairs. As early as 1992 the US military issued a new strategic document in which it proclaimed that the goal of American policy was to prevent any state from being able to challenge economically or militarily the dominant position of the United States.

Within the context of this global strategy, the domination of the Middle East and Central Asia—with their vast reserves of oil and natural gas—constitutes an absolute imperative. For the United States, unrestricted access to and control of these reserves—which represent a substantial portion of all known world-wide reserves—is critical not only to guarantee the satisfaction of its own domestic energy needs. In a world where the depletion of oil and natural gas reserves over the next quarter century is a critical issue, control over the distribution and allocation of these reserves would give the United States a stranglehold over the fate of all present and potential competitors.

With regard to this essential strategic aim—the establishment and consolidation of American hegemony in world affairs—there exists no significant or fundamental difference between George Bush and John Kerry. To the extent that differences do exist, they are principally of a tactical character—that is, over the degree to which the United States should be prepared to adapt its pursuit of hegemony to some sort of international imperialist multilateral framework.

But even those who are critical of Bush’s conduct of foreign policy recognize that a change of administration will not fundamentally alter its unilateralist direction. As Professor G. John Ikenberry has written:

“With the end of the cold war and the absence of serious geopolitical challengers, the United States is now able to act alone without serious costs, according to the proponents of unilateralism. If they are right, the international order is in the early stages of a significant transformation, triggered by a continuous and determined effort by the United States to disentangle itself from the multilateral restraints of an earlier era. It matters little who is president and what political party runs the government: the United States will exercise its power more directly, with less mediation or constraint by international rules, institutions, or alliances. The result will be a hegemonic, power-based international order. The rest of the world will complain but other nations will not be able or willing to impose sufficient costs on the United States to alter its growing unilateral orientation” (emphasis added). [1]

This conclusion is undoubtedly correct, for notwithstanding his tepid criticisms of the unilateralism of the Bush administration, Kerry continuously emphasizes that his administration would not hesitate to act unilaterally if that was deemed necessary in the “national interest.”

Ikenberry bemoans the accelerating tendency toward unilateralism, but he fails to explain the reason for this development. He refers repeatedly to the immense military superiority of the United States over all other national states, stressing that this essential geo-political fact allows the US to ignore, if it chooses to, international opposition to whatever policies it decides to pursue. But this explanation is inadequate. After all, in the immediate aftermath of World War II, when the military and economic superiority of the United States was at its zenith, the Truman administration was preoccupied with creating a complex of international multilateral structures.

When World War II came to a close, the dominant position of the United States in the structure of international capitalism was guaranteed far less by military power than by its massive and, at that point, unchallengeable economic superiority. The supreme symbol of American power was not the atomic bomb, but the dollar. The entire structure of international finance and trade rested on the dollar, which functioned as the world reserve currency, convertible into gold at the rate of $35 per ounce. The financial and industrial power of the United States provided the essential resources for an immense expansion of world economy.

The world situation today is vastly different than that which existed at the end of World War II. The global economic position of the United States has weakened dramatically during the past 60 years. Even by 1971 the relative weakening of the United States vis-à-vis its principal capitalist rivals in Europe and Japan brought about the collapse of the Bretton Woods system and its linchpin, dollar-gold convertibility. During the ensuing decades, the United States has been transformed from the world’s creditor into its greatest debtor. Sixty years ago, American industrial and financial power fueled the rebuilding of a world capitalist order that had been shattered by depression and war. Today, the viability of the American financial system depends upon the willingness of foreign states and investors to finance the staggering current accounts deficit of the United States.

The United States is now borrowing approximately $540 billion per year to cover its rapidly expanding current accounts deficit. This amounted to 5.4 percent of GDP during the first quarter of 2004, which is far higher than the previous record of 3.5 percent of GDP in 1987, when the dollar lost more than one-third its value and the stock market crashed.

There is a general consensus among bourgeois economists that the current accounts deficit—whose largest component is the negative balance of trade—is leading to a serious crisis. Many expect that a substantial decline in the dollar, with potentially destabilizing consequences internationally, is unavoidable and necessary.

According to Peter G. Peterson, the chairman of the Council on Foreign Relations:

“The next dollar run, should it happen, would likely lead to serious reverberations in the ‘real’ economy, including a loss of consumer and investor confidence, a severe contraction, and ultimately a global recession...

“Virtually none of the policy leaders, financial traders, and economists interviewed by this author [Peterson] believes the US current account deficit is sustainable at current levels for much longer than five more years. Many see a real risk of a crisis. Former Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker says the odds of this happening are around 75 percent within the next five years; former Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin talks of ‘a day of serious reckoning.’ What might trigger such a crisis? Almost anything: an act of terrorism, a bad day on Wall Street, a disappointing employment report, or even a testy remark by a central banker.” [2]

The noted economic analyst of the Financial Times, Martin Wolf, describes the situation in even blunter terms: “The US is now on the comfortable path to ruin. It is being driven along a road of ever-rising deficits and debt, both external and fiscal, that risk destroying the country’s credit and the global role of its currency. It is also, not coincidentally, likely to generate an unmanageable increase in US protectionism. Worse, the longer the process continues, the bigger the ultimate shock to the dollar and levels of domestic real spending will have to be. Unless trends change, 10 years from now the US will have fiscal debt and fiscal liabilities that are both over 100 percent of GDP. It will have lost control over its economic fate.” [3]

Recognition of its own deteriorating global economic position is a significant factor in the increasing reliance of the United States on military force. But, paradoxically, the vast cost of America’s far-flung military operations is yet another major burden weighing down on the national economy. The operation in Iraq is a case in point. It costs the United States one billion dollars every week to keep two divisions engaged in “stability operations.” To keep them engaged for a whole year would cost the entire GDP of New Zealand. [4] And the costs of the Iraq war are in addition to the already vast sums of money ear-marked for military spending. According to recent calculations by the Congressional Budget Office, the Bush administration has seriously underestimated the amount of money that will be required to fund military outlays over the next decade. An additional $1.1 trillion dollars in new spending will have to be allocated. [5]

Even more significant than the financial strains generated by the cost of American militarism is its destabilizing and potentially explosive impact on inter-imperialist and inter-state relations. The drive by the United States for hegemony does not take place in a geo-political vacuum. To the extent that the ambitions of the United States impinge on the vital interests of other states, confrontation and conflict is unavoidable.

The recriminations between the United States and Europe during the run-up to the invasion of Iraq reflected real conflicts over material interests. At some point these conflicts can lead to more than sharp diplomatic exchanges. In the end, “Old Europe” bit its lip and watched glumly as the United States invaded Iraq. But will it do the same as the US, in pursuit of new sources of oil, seeks to shove Europe aside in Africa? In July 2002, Assistant Secretary of State Walter Kansteiner declared during a visit to Nigeria that “African oil is of strategic national interest to us.” The Bush administration has identified six African oil producers as being of critical importance to the energy policy of the United States: Nigeria, Angola, Gabon, the Republic of Congo, Chad and Equatorial Guinea (the latter being the target of a plot masterminded by none other than Sir Mark Thatcher, the son of the illustrious former prime minister of Britain). And there are now discussions within the Defense Department about establishing a new African Command to coordinate the actions of the US military on that continent. [6]

Aside from potential conflicts with old imperialist rivals, the American thrust into Central Asia during the past five years increases the potential for military conflict with all other states with major interests in the future of that region, including Iran, India, China and Russia.

Let us grant that certain aspects of American foreign policy may be affected by a change of personnel in the White House, State Department and Pentagon. A Kerry administration may perhaps devote greater effort to winning the endorsement of its imperialist allies for one or another military action. But such differences are in the style, not in the substance, of policy. Within the framework of a capitalistic world system, the fundamental contradiction between a world economy and the nation-state system cannot be managed peacefully. The violent and aggressive character of American capitalism—like that of German capitalism in the 1930s and 1940s—is only the most extreme expression of the essentially predatory character of the imperialist system.

In May 1940, as Hitler’s armies swept across France, Leon Trotsky rejected facile explanations for the eruption of the war: “The present war—the second imperialist war—is not an accident,” he wrote. “It does not result from the will of this or that dictator. It was predicted long ago. It derived its origin from the contradictions of international capitalist interests. Contrary to the official fables designed to drug the people, the chief cause of war as of all other social evils—unemployment, the high cost of living, fascism, colonial oppression—is the private ownership of the means of production together with the bourgeois state which rests on this foundation ... So long ... as the main productive forces of society are held by trusts, i.e., isolated capitalist cliques, and so long as the national state remains a pliant tool in the hands of these cliques, the struggle for markets, for sources of raw materials, for the domination of the world, must inevitably assume a more and more destructive character.” [7]

How appropriate, timely and prescient these words are today! The vast and powerful economic forces that shape and determine the policies of American imperialism will not be altered by a mere change of personnel in Washington. The debate between Bush and Kerry over how best to realize the global ambitions of the United States is one that is taking place within the ruling elite, that small fraction of American society in which the vast bulk of national wealth is concentrated. The concerns of millions of ordinary working class Americans—who are, for the most part, against war—find absolutely no genuine expression in the official campaigns of either of the two imperialist parties.

To imagine that the direction of American policy will be significantly changed by the replacement of Bush by Kerry is to indulge in the most pathetic illusions. But there seems to be no shortage of such illusions among those who consider themselves on the “left.” For example, Mr. Tariq Ali—who back in the 1960s and 1970s was among the principal leaders of the International Marxist Group in Britain and who still describes himself as a socialist—is calling for a vote for Kerry. Mr. Ali’s record as a political analyst does not inspire confidence. In the late 1980s, when he was enthusiastically promoting Perestroika and Glasnost as a great advance for socialism in the Soviet Union, Tariq Ali dedicated a book that he had written on this subject to none other than Boris Yeltsin, “whose political courage has made him an important symbol throughout the country.” But let us not dwell on the past. Rather, let us turn to what Tariq Ali has to say now about the American elections.

Interviewed on August 5 by WBAI Radio in New York City, Tariq Ali asserted that the defeat of Bush would send a positive message overseas. “A defeat for a warmonger government would be seen as a step forward,” he said. “I don’t go beyond that, but there is no doubt in my mind that it would have an impact globally.”

In what sense would the election of Kerry be a step forward, and what would be the global impact of this development? Would it be followed by a withdrawal of US troops from Iraq? Would it bring about the withdrawal of US troops from Afghanistan? The answer to these questions is, unequivocally, no. As for the global impact of Bush’s defeat, it might actually facilitate efforts by the United States to win European support for the occupation of Iraq and other military actions that are in the planning stage. This, in fact, is one of the arguments that Kerry is making as he seeks to convince influential sections of the ruling elite to throw their support behind his candidacy.

Another argument for supporting Kerry appeared in the August 16 issue of the Nation. Explaining why she has finally joined the “Anyone But Bush” camp, Naomi Klein offered this novel argument: Bush is so hated by “progressives” that as long as he is president, it is impossible for them to think seriously about politics and the deeper causes of the war and the general crisis of society.

“This madness has to stop,” she writes, “and the fastest way of doing that is to elect John Kerry, not because he will be different but because in most key areas—Iraq, the ‘war on drugs,’ Israel/Palestine, free trade, corporate taxes—he will be just as bad. The main difference will be that as Kerry pursues these brutal policies, he will come off as intelligent, sane and blissfully dull. That’s why I’ve joined the Anybody But Bush camp: only with a bore like Kerry at the helm will we be finally able to put an end to the presidential pathologizing and focus on the issues again.”

Does such an argument even merit an answer? Discovering that all her friends have lost their heads, Ms. Klein has decided to join their company by removing her own.

There is a term which encompasses the sort of politics practiced by the Tariq Alis and Naomi Kleins of this world. It is opportunism, by which we mean the subordination of fundamental questions of political principal to pragmatic and purely tactical calculations. Indifferent toward theory (which they dismiss as merely “abstract”) and history, opportunists habitually evade the difficult problems of political development. When challenged by Marxists, who criticize their refusal to work through the implications of their tactical prescriptions from the standpoint of the independent political organization of the working class and the development of socialist class consciousness, the opportunists justify their pragmatic policies in the name of political realism. “You Marxists live in a world of theory,” they say. “We live in the ‘real’ world.”

Little do these pragmatic opportunists imagine that they are the most unrealistic of politicians. Their conception of reality is based on superficial appraisals of events, calculations of short-term advantages, and a substantial dose of self-deception—not on a scientific insight into the laws of the class struggle and its political dynamics.

All the arguments advanced by the opportunists in support of Kerry contribute, whatever their intention, to the political disorientation of the working class. It leaves the working class utterly unprepared for the aftermath of the election, when it will be confronted—regardless of who wins the election—with an immense intensification of political, economic and social crisis in the United States.

The failure of working class to free itself from the domination of the Democratic Party during the decades-long death agony of liberalism represents a historical tragedy. The last 35 years have witnessed the unstoppable evolution of the Democratic Party ever further to the right. This evolution arises principally from the weakening of the world position of American capitalism, which has undermined the material basis for the sort of social reformist liberalism that formed the basis of the Democratic Party’s appeal to the working class.

Combined with major changes in the social structure of American society, which includes a significant enrichment of those sections of the professional upper middle class (especially lawyers, university academics, etc.) from which the Democratic Party has traditionally recruited its political representatives, the general crisis of American capitalism has all but eliminated the constituency for liberal reformism within the capitalist class and its social periphery.

So advanced is the political decomposition of American liberalism that the Democratic Party is incapable of even mounting a serious political fight against the Bush administration. It cannot and will not articulate the antiwar sentiments of broad sections of working people. Quite the opposite: the principal aim of the Democratic Party has been to block the expression of political opposition to the war.

Let us review the process that led to the nomination of Senator John Kerry. It was universally recognized that the major issue fueling political activism during the primary campaigns of the winter of 2003-2004 was opposition to the war in Iraq. Polls indicated that approximately 80 percent of voters who identified themselves as Democrats opposed the invasion of Iraq. This accounted for the early popularity of Governor Howard Dean of Vermont. All the other candidates for the Democratic nomination, with the exception of Senator Joseph Lieberman, adapted themselves to the widespread antiwar sentiment. Lieberman, who proudly proclaimed his support for the invasion of Iraq and its continued occupation, never received more than 7 percent of the vote in any state primary. For several months, it appeared that Dean might actually win the nomination of the Democratic Party. Then he came under a ferocious assault within the media, which declared him to be “unelectable.” The media campaign was effective, because it spoke to the desire of ordinary Democratic voters to select a candidate who could actually win in the November elections.

It was this sentiment that led to the sudden revival of the candidacy of John Kerry, which had appeared to be going nowhere. Suddenly, with the gentle and skilled prodding of the media, it occurred to Democratic voters in Iowa and New Hampshire—the site of the first caucus and primary—that Kerry, as a war hero, would be immune to the type of jingoistic mudslinging that the Bush campaign would certainly employ during the national election. As Kerry had been carefully adapting his rhetoric to antiwar sentiments, playing down his Senate vote in favor of the war resolution and presenting himself as an opponent of Bush’s policies in Iraq, Democratic voters turned to him as an antiwar candidate who could win the national election. And so he sewed up the nomination by early March.

And that marked the end of all discussion of opposition to the invasion and occupation of Iraq inside the Democratic Party. The issue of the war—which had fueled all the political activism of the primary period—was transformed into a non-issue. Through deft maneuvering, the ruling elite guaranteed that the national campaign would not provide a forum for public opposition to the war in Iraq. The entire antiwar constituency has been effectively disenfranchised.

The outcome of this process demonstrated the degree to which the official political parties are completely independent of the broad masses in the United States. The concentration of political power in the hands of the two bourgeois parties complements the concentration of national wealth in the very small social strata that constitute the American ruling elite.

Social polarization and the concentration of wealth in the United States

It is impossible to understand the political situation in the United States without examining the most important feature of American society: the extreme concentration of wealth and corresponding growth of inequality.

This past June the death of Ronald Reagan evoked an extraordinary response within the ruling elite. Much more than maudlin sentimentality was involved in the effusive tributes. Rather, the death of Reagan provided the establishment an occasion to reflect on the changes in American society that have occurred over the last quarter century—that is, since the election of Reagan to the presidency in 1980—and to celebrate the staggering growth in its collective wealth.

To assist in this review, I have collected a number of charts that illustrate the concentration of wealth and the growth of social inequality. [8] Not only do they substantiate the extreme levels of inequality that exist today. These statistics provide an insight into the socio-economic background to critical political developments during the past quarter-century.

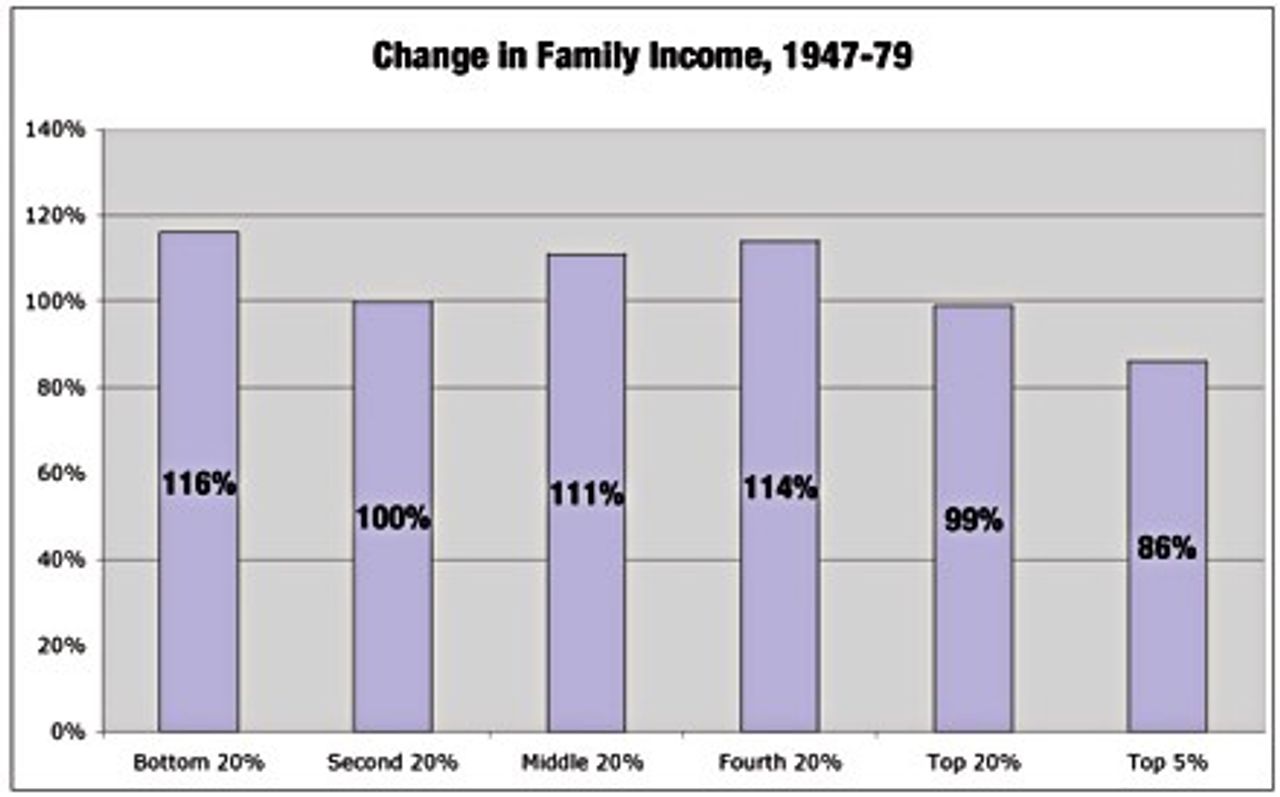

Chart 1 traces the change in family income between 1947 and 1979. These statistics show that the robust expansion of the American economy in the aftermath of World War II raised the family income of all sections of the population. The families whose income placed them in the lowest 20 percent realized a 116 percent increase in their income. The second 20 percent realized a 100 percent increase. The middle 20 percent saw a 114 percent increase. The top 20 percent saw a 99 percent increase and the top 5 percent realized an increase in family income of 86 percent. So we see that all sections of the population benefited substantially from the economic growth that followed the war, and, at least in percentage terms, the greatest gains were realized by the lower 80 percent of the people.

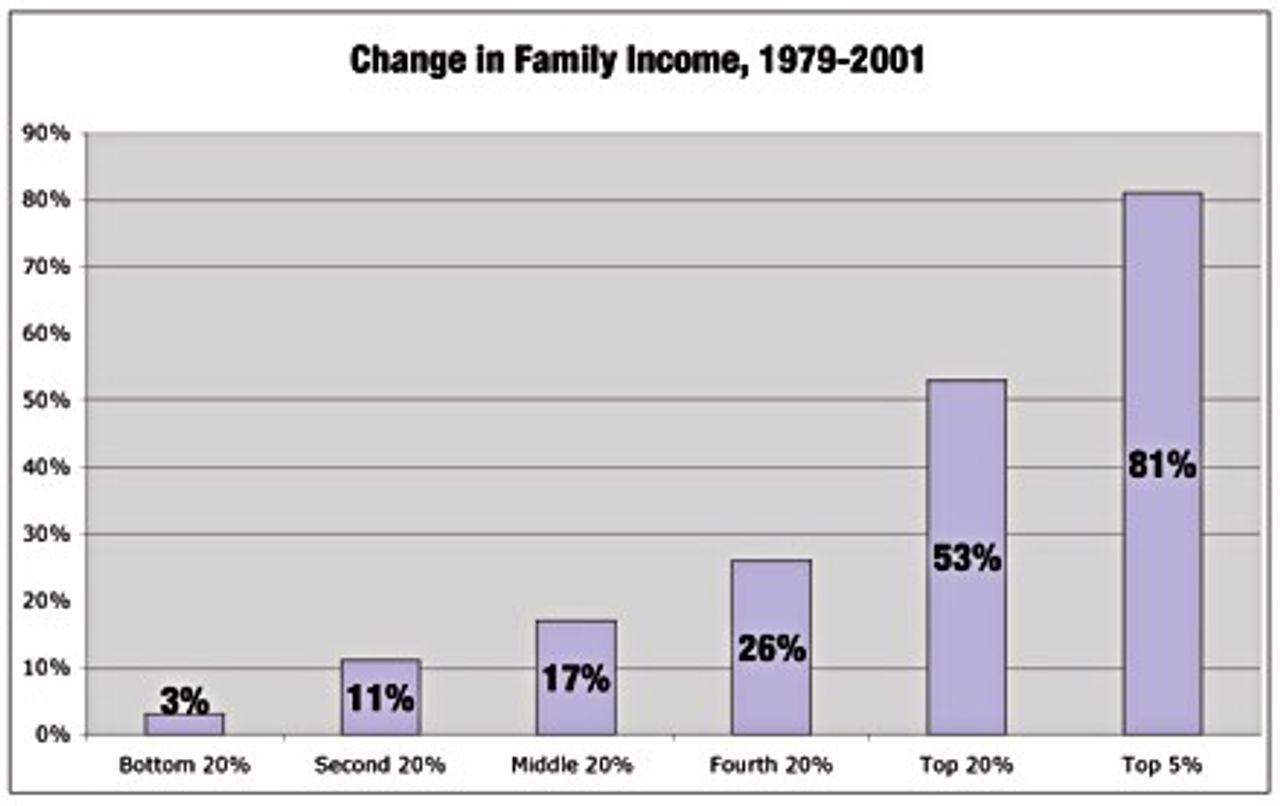

Now let us look at Chart 2, which tracks changes in family income between 1979 and 2001. What an extraordinary difference! We see that the bottom 80 percent of families realized very limited gains, while the wealthiest sections of the population, and especially the top 5 percent, continued to realize a substantial growth in family income. The bottom 20 percent of families realized only a 3 percent gain. The second 20 percent realized an 11 percent gain. The middle 20 percent realized a 17 percent gain, and the fourth 20 percent realized a 26 percent gain. But the top 20 percent saw its income rise by 53 percent, and, from within that group, family income of the top 5 percent rose by 81 percent.

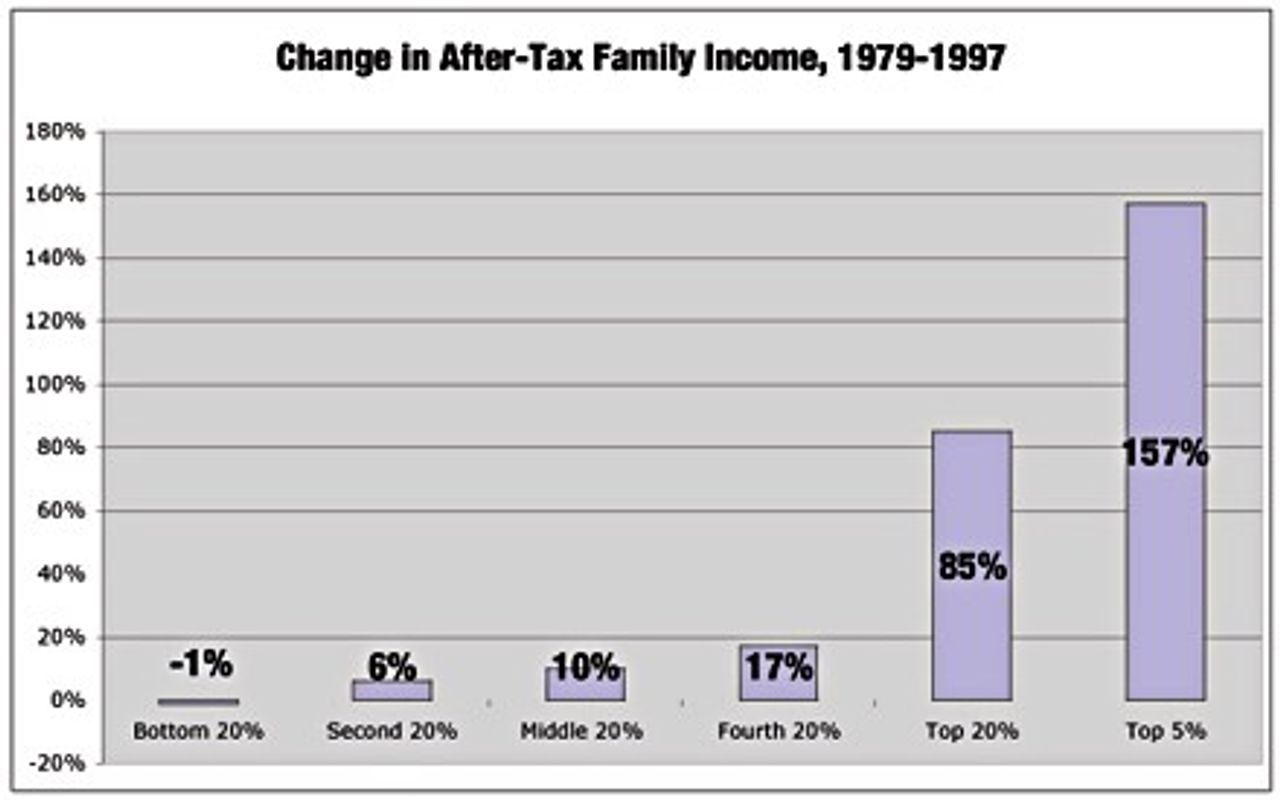

If we look at Chart 3, which tracks changes in family income after taxes, the inequality in family income is even more striking. Between 1979 and 1997, the bottom 20 percent saw a 1 percent decline in its family income. The top 5 percent saw a 157 percent increase!

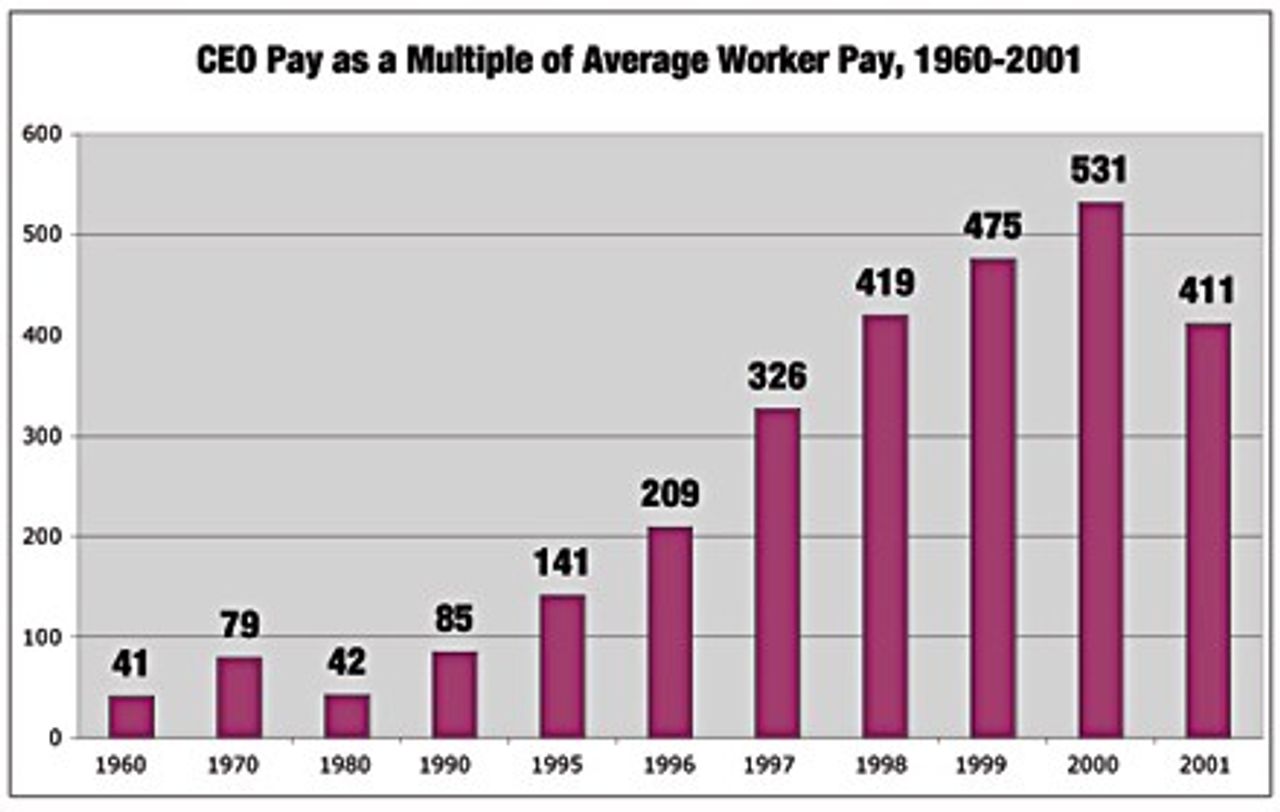

Now let us look at Chart 4, which shows CEO pay as a multiple of average worker pay between 1960 and 2001. In 1960, CEO pay at an average Fortune 100 company was 41 times that of an average factory worker. In 1970, due to a substantial rise in the stock market, that multiple had risen to 79. The 1970s, a decade of extreme economic crisis which witnessed a massive decline in share values, saw the multiple fall back to 42. Then look at what happened. By 1990, CEO pay had risen to 85 times the pay of an average worker. By 1996 it was at 209 times. By 2000 it had risen to 531 times!

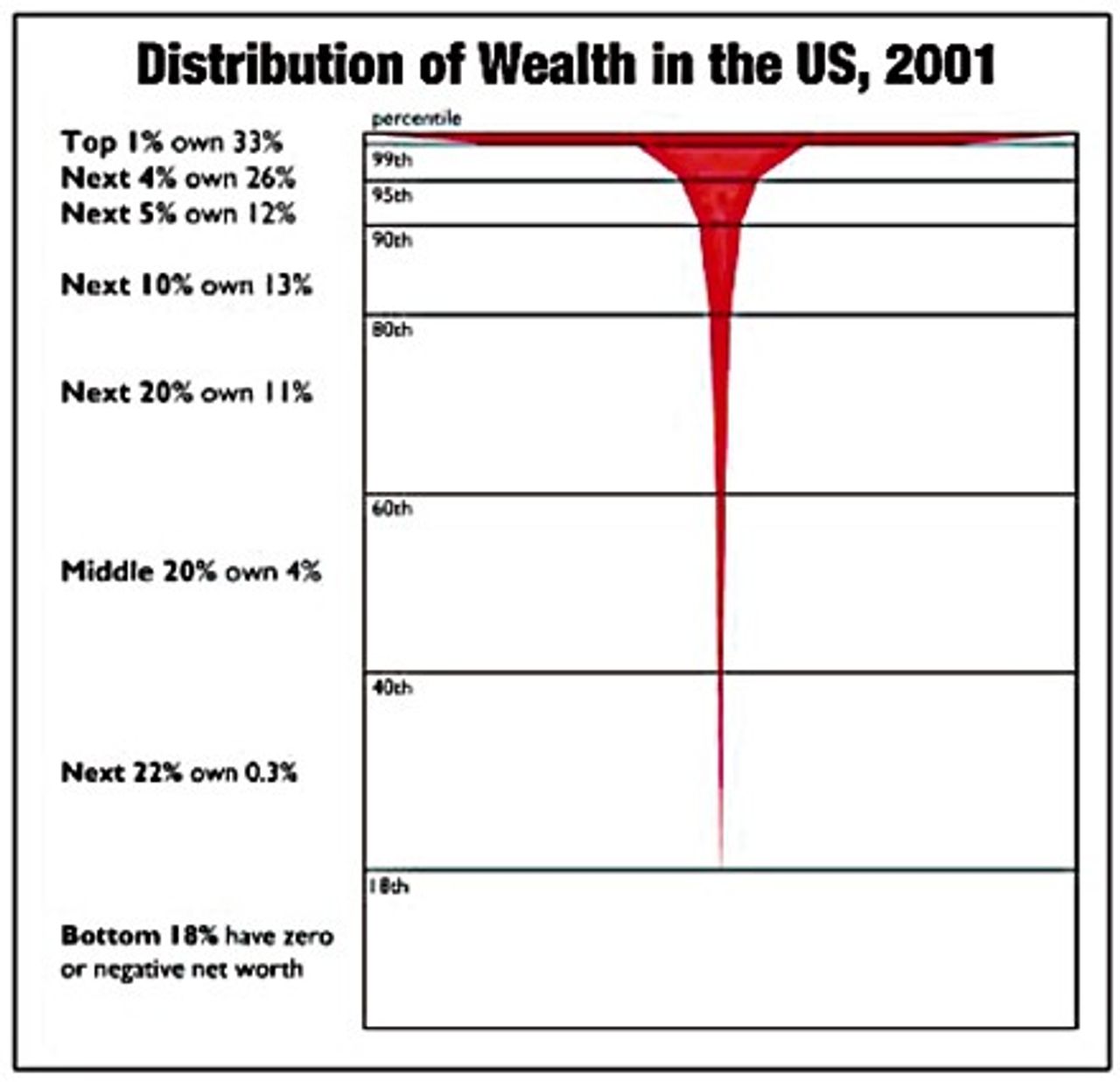

Chart 5 shows the distribution of wealth in the United States in the year 2001. The richest 1 percent of the population controls 33 percent of the national wealth. The next 4 percent own 26 percent. The next 5 percent owns 12 percent. Collectively, the richest 10 percent owns 71 percent of the national wealth. The 10 percent below them owns 13 percent. The next 20 percent owns 11 percent. The middle 20 percent owns just 4 percent. The next 22 percent owns 0.3 percent. The bottom 18 percent has zero or negative net worth.

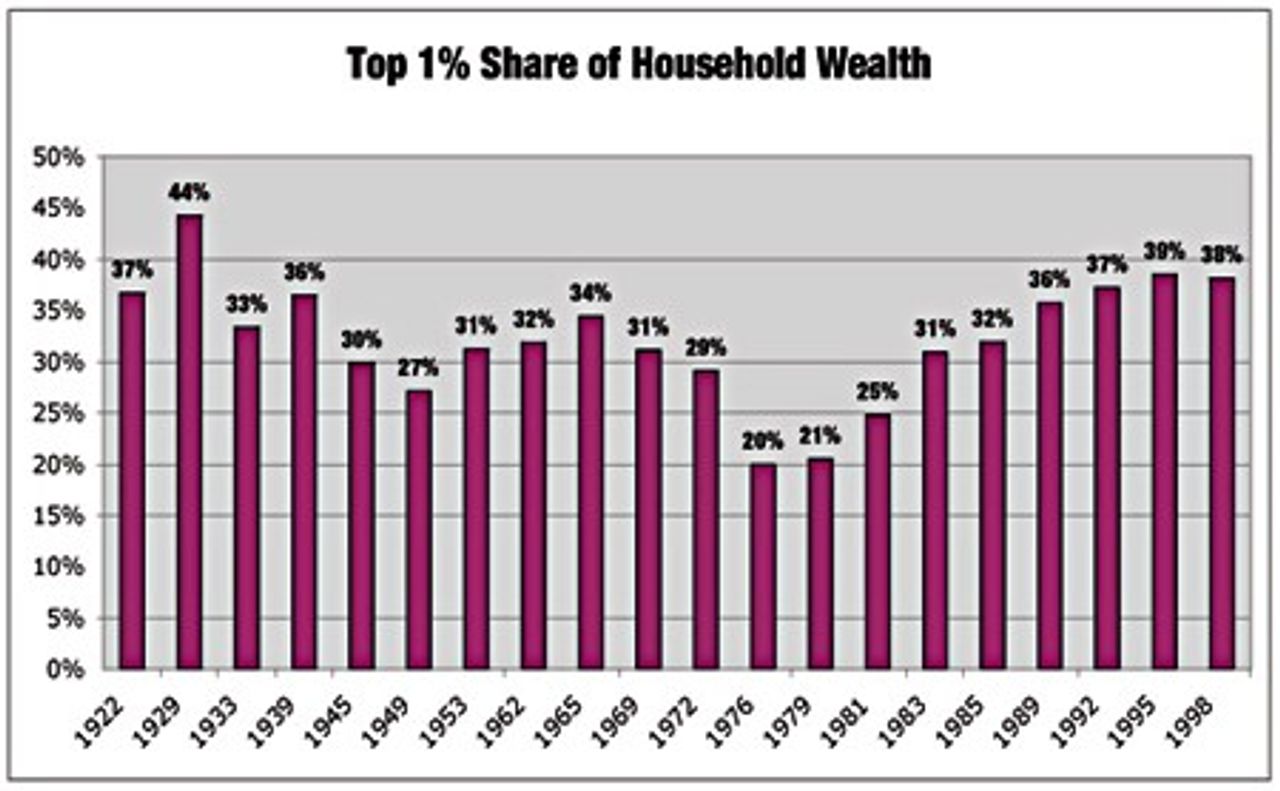

Chart 6 is especially important. An analysis of the fluctuation in the share of national wealth controlled by the top 1 percent of the population provides a profound insight into the social-class dynamics of American history over the last 80 years. After reaching its apogee in 1929, the share of national wealth controlled by the richest 1 percent declined significantly during the 1930s as a result of the depression. It stabilized and rose moderately during the late 1940s, 1950s and at a somewhat greater tempo during the 1960s. It then plunged dramatically in the 1970s—partly due to the gains achieved through the struggles of the working class. But an even greater factor was the impact of the world economic crisis of the 1970s, which resulted in a spectacular collapse in share prices.

The fall in share prices was a consequence of the strange combination of inflation and recession (stagflation), the decline in the profitability of the manufacturing sector of the US economy, and a general loss of confidence within the ruling class. The American bourgeoisie responded to the decline in its social position with a brutal counterattack against the working class.

In 1979, President Carter, a Democrat, appointed Paul Volcker as chairman of the Federal Reserve. He dramatically raised interest rates to unprecedented levels, which plunged the US economy into recession.

The conscious aim of this policy was to use mass unemployment to weaken the working class, facilitate a government-corporate assault on trade unionism, and lower living standards.

The policy of the bourgeoisie was spelled out by the leading magazine, BusinessWeek, which wrote in June 1980 that the transformation of American industry “will require sweeping changes in basic institutions, in the framework for economic policy making, and in the way in which the major actors on the economic scene—business, labor, government, and minorities—think about what they put into the economy and what they get out of it. From these changes must come a new social contract between these groups, based on a specific recognition of what each must contribute to accelerating economic growth and what each can expect to receive.”

Several months later, Ronald Reagan was elected president and the stage was set for an unprecedented government-sponsored assault on the working class, whose success was guaranteed by the betrayals of the trade union bureaucracy.

The results are reflected in the steadily rising share of national wealth accruing to the richest 1 percent.

A new study by Arthur Kennickell of the Federal Reserve Board shows that the wealthiest 1 percent own about $2.3 trillion in shares of stock, or about 53 percent of all individually or family-held shares. They also own 64 percent of all bonds held by families or individuals.

The reverse image of the spectacular wealth of the elite is the increasingly precarious situation which confronts the broad mass of American workers, and the really desperate situation in which the poorer sections of the working class find themselves.

An expanding category of the working class consists of what is described as “the working poor.” According to BusinessWeek, “Today, more than 28 million people, about a quarter of the work force between the ages of 18 and 64, earn less than $9.04 an hour, which translates into a full-time salary of $18,800 a year—the income that marks the federal poverty line for a family of four.”

BusinessWeek acknowledges that the working poor “labor in a nether-world of maximum insecurity, where one missed bus, one stalled engine, one sick kid means the difference between keeping a job and getting fired, between subsistence and setting off the financial tremors of turned-off telephones and $1,000 emergency room bills that can bury them in a mountain of subprime debt.

“At any moment, a boss pressured to pump profits can slash hours, shortchanging a family’s grocery budget—or conversely, force employees to work off the clock, wreaking havoc on child-care plans. Often, as they get close to putting in enough time to qualify for benefits, many see their schedules cut back. The time it takes to don uniforms, go to the bathroom, or take breaks routinely goes unpaid. Complain, and there is always someone younger, cheaper, and newer to the US willing to work for less.” [9]

This is the United States of America in the year 2004!

The American crisis and world prospects for socialism

The extreme levels of wealth concentration and social inequality underlie the breakdown of bourgeois democracy in the United States. The vast expansion of police state measures undertaken by the government during the past three years arise not from the so-called “terrorist threat,” but from the extreme sharpening of social and class tensions within American society.

The most conspicuous and fatal weakness of radical-left, in contrast to Marxist, politics in the United States (and, I might add, internationally) is its inability to conceive of a fundamental crisis of the capitalist system in the United States, or to recognize the working class as the basic revolutionary force in American society. Socially alienated from the working class and politically intoxicated by the media-generated images of American omnipotence, the left-radical milieu sees no objective basis upon which a struggle can be waged against capitalist rule in the United States. This accounts for the extreme demoralization of the radical left, which feels hopelessly isolated. It fails completely to see how the interaction of global economic contradictions and intensifying class tensions within the United States is creating conditions for a revolutionary explosion in the very center of world imperialism.

This is not a weakness that is peculiar to the American left. It is very much an international phenomenon. There are many aspects of this general political crisis on the left. But in analyzing and explaining the causes of this crisis, it is important to place special emphasis on the failure of so much of the left to systematically study and assimilate the strategic historical experiences of the struggle for socialism in the twentieth century—in particular, the causes of the degeneration and ultimate collapse of the Soviet Union.

In the absence of a systematic working through of the essential experiences of the international socialist movement in the twentieth century, the collapse of the USSR has been seen to a great extent as a demonstration of the failure of socialism and the bankruptcy of a revolutionary perspective based on the working class.

However, to those who have studied this history—who recognize that the collapse of the USSR and the defeats of the working class were not inevitable and preordained, but were the consequences of false policies, based on anti-Marxist and reactionary conceptions of a national road to socialism—the present political situation appears very different. The lessons drawn from a study of the past furnish a key to an understanding of the present.

We are approaching an historical anniversary in which two great advances in theoretical thought will be celebrated. The year 2005 will mark the centenary of Einstein’s initial formulation of the theory of relativity, which led to a transformation of man’s conception of the universe. It is also the centenary of the 1905 Revolution in Russia, which was the first great eruption of revolutionary working class struggle in the twentieth century. The events of that year provided the impulse for an immense advance in the theoretical thought of the international socialist movement—the formulation of the theory of permanent revolution by Leon Trotsky.

Challenging prevailing nationalistic conceptions which evaluated the prospects for socialism in any given country on the basis of the level of its own industrial development, Trotsky demonstrated that the dynamic impulse for socialism arose from the general development of world economy. The decisive factor in the emergence of a revolutionary crisis in any country was not a product of a particular set of exceptional national conditions, but of the contradictions of international capitalism. Moreover, as the causes of socialist revolution lay in global economic conditions, there could be in the aftermath of the seizure of power by the working class no national road to socialism. The only viable strategy for the working class was one that conceived of the struggle for and the building of socialism as a unified, interdependent, world revolutionary process.

The theoretical and political issues posed by Trotsky’s theory of permanent revolution are not merely abstract historical problems. They form the basis for an understanding of the present world situation and the tasks of the working class.

We could, of course, examine at length the manner in which Stalin’s conception of a national road to socialism—proclaimed under the banner of “socialism in one country” in opposition to the theory of permanent revolution—led ultimately to the destruction of the USSR. The study of this experience constitutes the basic source of theoretical and political understanding of the fate of the international socialist movement in the twentieth century. Moreover, the catastrophic conditions that prevail in present-day Russia demonstrate the consequences of the betrayal of the international strategy upon which the conquest of power by the Bolsheviks in 1917 was based.

We might also look at the fate of China. It is not so many years ago that radical left tendencies believed that they had discovered in the banal stupidities of Maoism (“power comes out of the barrel of a gun”) the last word in revolutionary thought. Indeed, among Maoist groups all over the world were to be found the most vicious opponents of Trotskyism. And even among radical tendencies that claimed a degree of political sympathy for the ideas of Leon Trotsky, the view was often expressed that the “success” of the Chinese Revolution refuted Trotsky’s claims that the building of the Fourth International was essential to the victory of socialism. Had not Mao, and later Ho Chi Minh, not to mention Castro, superseded Trotsky and the old-fashioned concepts, methods, perspectives and strategy of archaic “classical Marxism?” As for the Chinese Trotskyists, who had subjected the bureaucratic character and non-proletarian base of the Maoist party to criticism, and who paid for their theoretical intransigence with decades of imprisonment—were they not hopeless “sectarians,” “refugees from the revolution?”

Let us “fast-forward” to the year 2004. What has become of Mao’s China? It is the cheap-labor foundation upon which the survival of world capitalism presently depends. Subtract China from the equations of the modern world economy and what would be the present position of American capitalism? In the year 2003 bilateral trade between the United States and China surpassed $190 billion. It is the third largest trading partner of the United States, after Canada and Mexico. The American trade deficit with China totaled $135 billion, the largest deficit that it has ever run with any country in history.

American capital is pouring into China, as US capitalists seek to snap up assets that are being sold off by the state and deepen their penetration of the vast Chinese internal market.

What is it that attracts American capitalists to China? Their “werewolf” appetite for surplus value and profits are whetted above all by the low cost of labor. The Chinese worker earns one-fifteenth to one-twentieth the wage paid to a comparable American or European worker. In the garment industry, which is now dominated by China, the average wage of 40 cents per hour is less than one-third the wage paid to a worker in Mexico. The United Nations estimates that 16.1 percent of Chinese (about 208 million) are paid less than $1.00 a day; and 47.3 percent of the population (about 615 million) live on less than $2.00 per day. This is what makes China, according to the World Bank, one of the most favorable investment climates in the world. [10]

The opening up of China to super exploitation by the imperialists has extracted a terrible social price. While the benefits of imperialist investment accrue to the corrupt milieu of the Chinese state and party bureaucracy, the impact upon hundreds of millions of people—especially in the rural areas—has been nothing short of catastrophic.

When one studies the fate of China and its role in the world economy, it is not an exaggeration to state that Maoism, which is one variant of Stalinism, has made a significant contribution to the survival of American and world capitalism.

However, there is another side to this situation. The very dependence of American and international capital upon China’s low-wage labor resources renders them highly vulnerable to the explosive social consequences that must inevitably flow from the super exploitation of the country.

Thus, we are entering into a new period that will be characterized by a growing coincidence of revolutionary class struggle on a world scale. The challenge facing the Marxist movement today is to imbue this world movement with consciousness of its essentially international character, to reanimate it with socialist convictions, and to educate it on the basis of the lessons of the past century. This is the perspective upon which the International Committee of the Fourth International, the World Socialist Web Site, and the Socialist Equality Party are basing their intervention in the 2004 election.

During the past six months, the Socialist Equality Party has been conducting an intense and vigorous campaign to place its candidates for national, state and local office on the ballot in as many states as possible. It is a difficult process, in which our candidates are compelled to fight against undemocratic ballot laws which are designed to prevent third-party candidates from obtaining official ballot status. Many states demand that third parties obtain tens of thousands of signatures, making it all but impossible to appear on the ballot. This year, the Democratic Party is, as a matter of policy, systematically challenging the signatures that appear on the petitions of third-party candidates.

The Socialist Equality Party has been dealing with such challenges during the past few months. So far we have placed our presidential and vice presidential candidates on the ballot in New Jersey, Iowa, Colorado and Washington. We expect that Bill Van Auken and Jim Lawrence will also be certified in Minnesota. The SEP will also have state and local candidates on the ballot in Maine, Michigan and Illinois.

We are asking working people to cast their votes for our candidates wherever they are on the ballot. In the case of one congressional candidate—David Lawrence in Ohio—who has been kept off the ballot because of blatantly undemocratic laws, we are asking voters to write in his name.

But the central purpose of our campaign is not to win votes. Rather, it is to contribute to the political education of the working class, to deepen its understanding of world events and to develop its class consciousness.

Nearly 66 years ago, upon founding the Fourth International, Leon Trotsky said:

“We are not a party as other parties. Our ambition is not only to have more members, more papers, more money in the treasury, more deputies. All that is necessary, but only as a means. Our aim is the full material and spiritual liberation of the toilers and the exploited through the socialist revolution. Nobody will prepare it and nobody will guide it but ourselves.”

Two thirds of a century later, that remains the perspective of the International Committee of the Fourth International. But there are no shortcuts to its realization. Socialism is not the sum total of clever tactics, let alone the unconscious by-product of militant trade union demands and protest demonstrations. Such forms of struggle have a role to play, but they are not a substitute for the explicit fight for Marxism. The development of a scientific world revolutionary outlook among a substantial section of class-conscious workers is essential. Socialism can be achieved only through a tireless and unrelenting struggle to explain that there exists no solution to the problems of our epoch other than the conquest of power on a world scale, and, on this basis, the rebuilding of a powerful international socialist culture within the working class.

Notes:

1. “America and the Ambivalence of Power,” Current History, November 2003, pp. 377-82

2. “Riding for a Fall,” Foreign Affairs, September/October 2004, p.119

3. August 17, 2004

4. “Riding for a Fall,” p. 112

5. Ibid, p. 113

6. See “African Oil and US Security Policy,” by Michael T. Klare and Daniel Volman, Current History, May 2004

7. “Manifesto of the Fourth International,” in Writings of Leon Trotsky (1939-40) [New York, 2001], p. 223

8. The charts have been reproduced from material found at www.inequality.org

9. BusinessWeek, May 31, 2004, p. 61

10. “Partners and Competitors: Coming to terms with the new US-China economic relationship,” by Bates Gill and Sue Ann Tay, Center for Strategic and International Studies