This is the first in a series of articles on the recent Vancouver International Film Festival

The failure in recent times of the commercial or ‘independent’ film world to offer a serious accounting of contemporary circumstances has created an immense vacuum. This has been filled in part, although only in part, by nonfiction films. The argument might be made that, in any case, fiction filmmaking could and should never cover the same ground as documentary work and there is, of course, some truth to that. But it is a limited truth and ought not be made into a principle.

In its own distinctive fashion, fiction too needs to be treating the way people live in society, and its terribly poor performance on that score is a disgrace. Hollywood genuinely deserves its faltering box office. In 1948, 65 percent of the US population, for example, went to the cinema every week; by last year, that figure had dropped to 10 percent. Attendance is down again in 2005. Why should people continue to spend a good deal of increasingly hard-earned money on films that are neither entertaining, affecting or enlightening?

The war in Iraq is one of the enormous events of our time that cinema needs to treat. Tens of thousands, or more, have died, countless others have been wounded, a country’s infrastructure has been destroyed, cities razed to the ground and untold numbers of lives made miserable, as the American ruling elite pursues its goal of world domination. The US population was dragged into the war, whose tragic consequences have only begun to unfold, on the basis of a torrent of lies. The entire American establishment is implicated.

Of the documentary works that have attempted to treat the circumstances surrounding the war, The Oil Factor: Behind the War on Terror, directed by Gerard Ungerman and Audrey Brohy, seems one of the most ambitious and comprehensive. Made in 2004, the film screened at the Vancouver festival this year. It is worth seeing.

Of the documentary works that have attempted to treat the circumstances surrounding the war, The Oil Factor: Behind the War on Terror, directed by Gerard Ungerman and Audrey Brohy, seems one of the most ambitious and comprehensive. Made in 2004, the film screened at the Vancouver festival this year. It is worth seeing.

Ungerman and Brohy have done their homework. As its title suggests, The Oil Factor places the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq—in fact, the entire so-called ‘global war on terror’—within a definite geopolitical context: the drive by the US ruling elite to organize a stranglehold over world oil reserves. The co-directors make no secret of their intentions. In an interview, the French-born Ungerman told me that the pair are concerned about “the powers grabbing more and more.” They conceive of their work as an “independent form of media,” appealing to a broad popular movement against the “capitalist apparatus.”

In the film’s opening moments, in the wake of the September 11 attacks, George W. Bush rambles on about the “thousands of dangerous killers” who threaten the US population. Scenes of the run-up to the invasion of Iraq in March 2003 are followed by appalling footage of Iraqi civilian casualties, sights rarely or never seen in the US. On May 1, 2003, in his pathetic flight jacket, aboard the USS Abraham Lincoln, in front of the giant “Mission Accomplished” banner, Bush declares “major combat operations have ended.”

The film backtracks, taking up the issue of “weapons of mass destruction.” It exposes the role and history of figures such as Ahmed Chalabi, a convicted embezzler and longtime US stooge, one of the key sources for the WMD claims of the Bush administration.

Contrary to the claims of Gary Schmitt, of the Project for the New American Century, the well-connected, right-wing think tank, who assures the camera that the Iraq conflict is not about oil, the filmmakers point to certain inescapable facts: the skyrocketing use of oil for fuels, plastics and chemicals (with the US consuming 20 million barrels a day) under conditions of dwindling reserves of the critical substance. Oil production is expected to dry up in the US and Europe by 2010, in eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union by 2013 and in Asia by 2018.

The film, narrated by actor Ed Asner, observes that seven pages of notes from Vice President Dick Cheney’s infamous 2001 energy task force that have been made public contained detailed information about Iraqi oilfields, pipelines, refineries and terminals, as well as documents featuring maps of oilfields in Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates. The Oil Factor notes that ¾ of the world’s oil and natural gas is located in the Middle East and Central Asia, the focal point of the ‘war on terror.’

A commentator from Jane’s, the defense and security analysts, argues that the US efforts concern “oil for power rather than oil for profit.” He points out that US troops immediately seized Iraqi oilfields in 2003, while they failed to secure nuclear facilities. In fact, villagers were able to make away with barrels of radioactive materials.

Speaking to the media, Paul Bremer, former administrator of the US-led occupation in Iraq, uses words such as “freedom” and “democracy,” but the filmmakers argue that the US has no interest in genuinely free elections that would more than likely bring to power a regime friendly to Iran, “a target [of Washington’s] since 1979.”

Ungerman and Brohy explore the intimate connections of leading Bush administration officials (Cheney, Rice, etc.) to the oil industry. They describe the “privatized occupation,” in which corporations like Bechtel and Halliburton are cashing in on tens of billions of dollars of contracts. A Bechtel executive, interviewed in Baghdad, is quite candid about this. Moreover, the film discusses “the quiet plan to privatize Iraqi oil.” A flood of money for Iraq ‘reconstruction,’ while the US infrastructure decays? Schmitt of the PNAC arrogantly declares, “Our schools get plenty of money.”

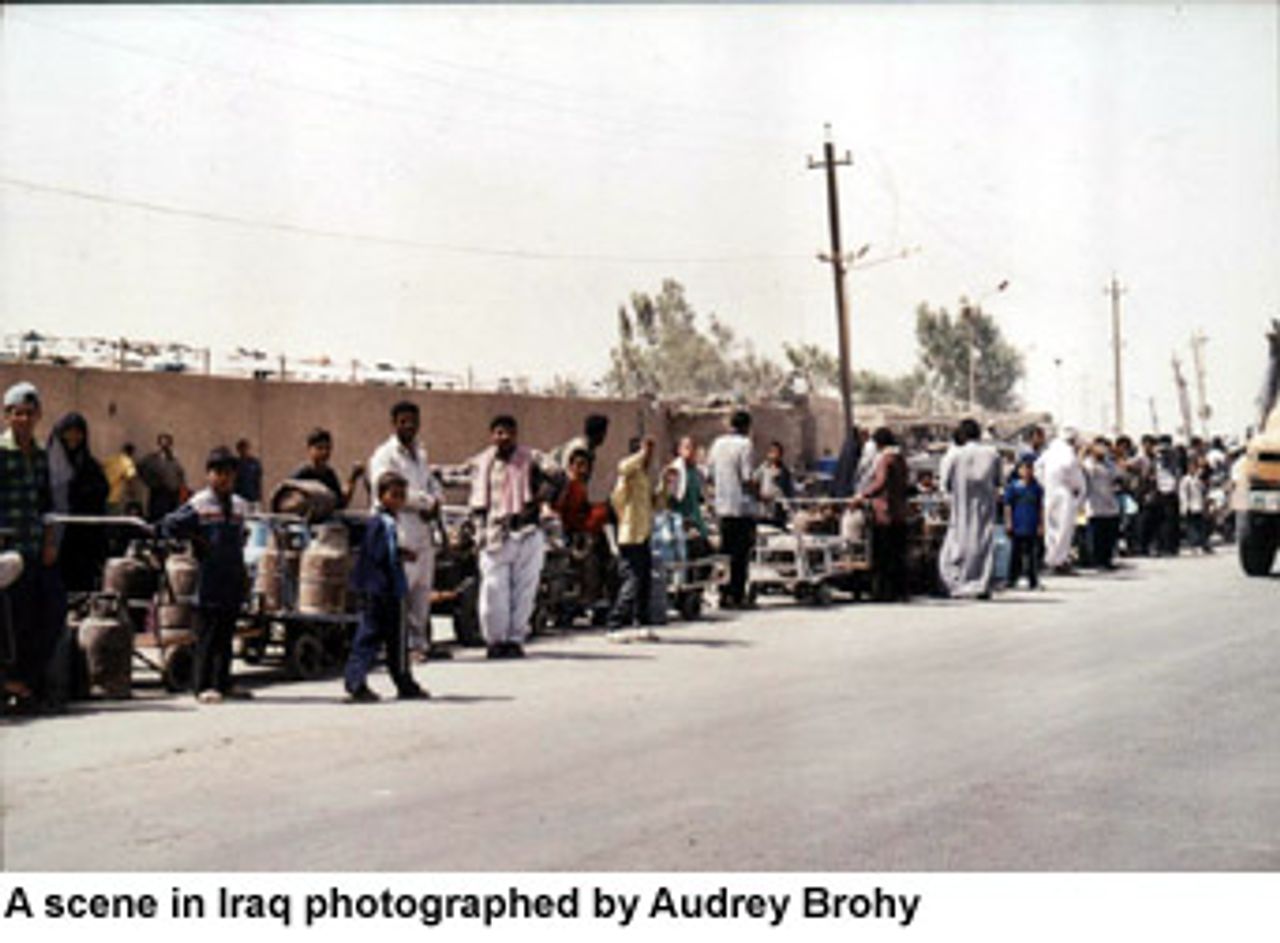

Asner explains that none of the promises of improvement in the living conditions of the Iraqis have been fulfilled. “Deep frustration” and anger persist over electricity and water supply problems, which have worsened under US occupation. There is no money for hospitals. Iraqis line up for gas and heating fuel. “This is not liberation,” one man tells the filmmakers. In fact, there criminality and chaos prevails.

The insurgency, The Oil Factor makes clear, is principally composed of Iraqi nationalist opposition, not support for “Saddam,” as the military and the American media insist. US searches, raids and the arrest of thousands have only strengthened resistance. The horrifying conditions at Abu Ghraib are once again documented. We see images of US wounded and dead, banned by the Pentagon from appearing on the media.

The film turns its attention to the Afghan invasion, focusing on the proximity of that afflicted country to the Caspian region, with its substantial oil and gas. Ungerman and Brohy document the US role in financing and inciting the Islamicist elements during their conflict with the Soviet army. The history of American intelligence with the Pakistani secret service, through whom it employed figures like Osama bin Laden, is briefly recounted.

Ahmed Rashid, author of Taliban: Militant Islam, Oil and Fundamentalism in Central Asia, provides an account of the US relations with the Taliban, before and after their ascension to power in 1996. Washington hoped that the fundamentalist movement in Afghanistan, which was staunchly anti-Iranian, would be more favorable to US concerns, including a proposed pipeline deal. The Taliban, however, proved less than reliable allies and their granting of refuge to bin Laden angered the US. They were marked for removal. The invasion of Afghanistan was a foregone conclusion; September 11 provided the pretext.

Ungerman and Brohy’s film details as well the conditions in the illegal internment camp in Guantánamo, Cuba, where prisoners, termed “enemy combatants,” are incarcerated.

The wretched conditions in Afghanistan, under US and allied nations’ occupation, are also examined: disease, poverty, warlordism ... The US puppet Karzai signs the pipeline deal.

The film argues that US military hegemony covers 90 percent of the oil-rich regions of the Middle East and Central Asia, with permanent American bases now a central fact of life.

Finally, The Oil Factor notes that US plans to grab the world’s critical resources demand sacrifices from the American people, as the military targets youth. Schmitt of the PNAC ominously notes that the US military is “too small” for its contemporary tasks.

The film is ambitious, with far-reaching political implications. In a conversation, the Los Angeles-based couple, who have worked together since 1995, do not shy away from those implications. “We try to be comprehensive,” explains Ungerman, who has a background in France as an infantry officer and a print media journalist. He explains that he has experienced a significant shift to the left in his thinking.

Brohy, Swiss-born and trained in the theater, remarks that the pair distribute The Oil Factor themselves, making the film available to groups and schools all over the US. They have shown the film in Boston, Washington, New York, Seattle and many parts in between, in conjunction with the antiwar movement. The reaction, she says, has been “fantastic.” In small towns too, perhaps most of all—in Colorado, New Mexico and elsewhere. People ask all the time, “What can we do?” In St. Paul, Minnesota, 300 people showed up. There was a “huge showing” in Las Vegas, New Mexico.

Ungerman tells me that a high school in Kentucky spent an entire day discussing the Gulf War, which included a showing of one of their previous films, Hidden Wars of Desert Storm. Students, Gulf War veterans and parents participated.

The response is strongest, Brohy asserts, where “people are oppressed by Fox News” and feel “isolated.”

Traveling around the US and showing their film, of course, occasionally they get told that they are “f______ French” and “anti-American” and should shut their mouths. I advise them not to be the slightest bit defensive, or apologetic. First of all, they are telling the truth and that is the only thing that really matters. Second, the Bush administration has declared war on the rest of the world, and the world’s population has every right to respond. As to being “anti-American,” there are two Americas, the “America” of Bush and the wealthy elite, to which one has every right to be hostile, and another “America,” made up of its working population.

On the general situation, Ungerman says, “The neoconservatives want to have their hands on the [oil] tap. This means a direct confrontation with other countries, including China. The Europeans want to please the US, people like Berlusconi and Blair. They get the crumbs from the US table. Iran is next, I think. Then Venezuela, Nigeria perhaps. They don’t have the manpower at this point.”

I note that the war on Iraq was the consensus policy of the entire American ruling elite, not simply the Republican neoconservatives. Brohy agrees, “The Democrats simply have different tactics.” Ungerman compares the Republicans to robbers who “shove a gun in your face” and the Democrats to burglars who break in to your house at night when no one is home. I point out that their film is an indictment of the entire political and media establishment. It will not be part of Hillary Clinton’s campaign material if she runs in 2008, I suggest, and they laughingly agree.

We discuss the political situation in the US in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina: the growing social antagonisms, the violence and brutality of the ruling elite. Brohy observes that this might be the “perfect ground for revolution.” Ungerman thinks that a Hitler-type movement could emerge. Well, I put in, revolution and counterrevolution are the two possible outcomes.

Visit www.theoilfactor.com for more information.

Two films about life in the US

This Divided State (Steven Greenstreet) and After Innocence (Jessica Sanders) treat less adequately, and less boldly, aspects of American society.

The first film concerns the attempt by right-wing forces in September 2004 to block a speaking engagement at Utah Valley State College in Orem, Utah—a town that promotes itself as “Family City USA”—by muckraking filmmaker Michael Moore.

The invitation to Moore, extended by the student government, outrages reactionary forces at the school, 75 percent of whose students are Mormon, and in the town. They petition to rescind the invitation, claiming that the school is spending money to invite an “un-American” figure, whose views do not represent the community’s views. Kay Anderson, a gimlet-eyed local businessman, spearheads the campaign. Anderson is a definite type: a small-town Babbitt as a sinister reactionary. At one point he offers to buy every ticket if the school will cancel Moore’s talk. Fortunately, the student body leaders and the school administration hold their ground—barely, one senses—and the engagement goes ahead as planned.

However, apparently to “balance” Moore, the school invites right-wing talk show host Sean Hannity, a fast-talking, foul demagogue. And when Moore does arrive, moreover, he offers up his worst side, arguing unconvincingly and half-heartedly for a vote for John Kerry. The filmmaker is content to remain on the sidelines and passively record the confused events.

America’s record as an imprisoner and executioner of human beings is disgraceful, one of the clearest indicators of a socially stratified and diseased society. After Innocence recounts the stories of some of the men who have been freed—after decades, in some cases, of incarceration—on the basis of DNA evidence.

The cases are enough to make one’s hair stand on end. The most brutal is that of Nick Yarris, who spent 23 years on death row (8,057 days), charged wrongly with rape and murder. For the first two years in prison, officials did not allow him to talk (illegally, presumably). He spent much of his time in solitary confinement, in a prison condemned by the UN for torture.

Outside after more than two decades, Yarris finds it difficult to breathe, “I’ve been breathing refiltered air for 23 years. I’m allergic to fresh air,” he explains. He cannot speak about some of things that occurred in prison. “I’m one of the strongest human beings ever created,” he claims, and one is not in a position to argue.

The film explores a number of similar stories, men either framed up or incompetently tried, from working class backgrounds, black and white, dealt with in a combination of indifference and ruthlessness. One former inmate explains how, at his sentencing, “I told the judge to go to hell. ‘You know I didn’t kill anyone.’”

Another victim, Vincent Moto, of Philadelphia, spent 10 ½ years in prison on false rape charges. On leaving prison, he received no compensation. “They didn’t give me anything.” Another man points out that if he had been released on parole, he would have gotten certain benefits. He was given $5.37 and “let loose.”

The film’s focal point is the work of the Innocence Project, co-founded by attorney Barry Scheck, which has crusaded for the exoneration of prisoners unjustly locked up. The organization receives thousands of appeals from prisoners (a staff member opens file cabinet drawers full of as yet unopened letters), an indication of the current state of the American legal system.

The stories are extraordinarily moving. Wilton Dedge, of Port St. John, Florida, spent 22 years in prison on charges of raping a 17-year-old girl in 1982. For three years after DNA evidence proved his innocence, the authorities persisted in persecuting him. He was only released in September 2004. As his attorney explains, the authorities “didn’t care whether he was innocent or not.” He was let go without so much as a bus ticket home. Dedge is now campaigning for compensation for those wrongfully convicted, a measure that state legal authorities, naturally, are opposing.

The efforts of the lawyers and law students who offer their services in the cause of exonerating the innocent are inspiring. One sees something about what is best in America.

After Innocence begs many of the critical social questions, however. How could such an appalling state of affairs exist in a genuinely democratic society? Injustice is clearly endemic to the ‘justice’ system. To propose DNA testing as the panacea is simply unserious. In any case, what about the “guilty” who are sent away to rot in prisons? Are they not victims too, in the final analysis, of a socially polarized society, where there are shrinking economic or educational opportunities, or none at all, for wide layers of the population? None of the victims in the film were stockbrokers or corporate executives, and they are not likely to be. The film had the opportunity to take a sharp and critical look at American society and also contented itself with the least penetrating conclusions.

The undocumented

To the Other Side (Natalia Almada) cannot quite make up its mind as to its central focus. It follows a 23-year-old Mexican, Magdiel, from La Reforma, an economically devastated town that is also the center of drug trafficking. Magdiel is a corridista, a composer of songs celebrating the exploits of gangsters and smugglers. He dreams about life in the US. The film spends some of its time on corridos and their composer/singers, including the legendary Chalino Sanchez, who was murdered in 1992.

The conditions are desperate, but the fact that Pancho Villa has been replaced in corridos by drug traffickers and “coyotes” (those who guide undocumented immigrants into the US for money) is nothing to crow about. The filmmaker seems too prone to adapt herself to backwardness.

The most affecting moments are provided by some of the “illegal” immigrants themselves, and not the corridista variety. A number are remarkably clear-sighted not only about the US, but about Mexico. A group of self-righteous US vigilantes ‘captures” (without a struggle) a group of former farm workers trying to cross the border. One man tells the filmmaker, “The government of Mexico doesn’t care. They still eat whether or not we have work.”

To be continued