Over 27,000 machinists began the second month of their strike against the Boeing Corporation Saturday. The 2005 strike lasted 28 days. Workers are maintaining a dogged opposition to the company's demand for concessions on pensions and health care benefits and increased job-outsourcing and off-shoring. No negotiations have taken place since the strike began September 6.

WSWS reporters spoke to Boeing workers Saturday, at a number of picket lines outside the massive plant in Everett, Washington, north of Seattle.

According to the company's web site, the Everett facility, which builds the Boeing 747, 767, 777 and 787 airplanes, includes the largest building in the world by volume, some 472 million cubic feet (13.3 million cubic meters). "Its footprint covers 98.3 acres," says Boeing. Some 25,000 employees work three shifts at the Everett site.

The company's web site goes on: "With six million parts in the 747 and more than three million each on the 767 and the 777, the systems used to order, track and distribute the correct part to the correct assembly point at the right time is no less complex. Developing the plans and follow-through to successfully assemble all of those parts is one of the things in which Boeing employees take great pride."

All of this complex and socially necessary activity, however, is a privately-owned operation and driven by profit. The company, which makes billions annually and whose executives are richly rewarded, is currently attempting to wrest major concessions from its unionized workers, members of the International Association of Machinists. Boeing workers are determined to resist the company's demands.

At the first picket location in Everett, strikers had erected a number of tent-like structures to protect themselves from the elements, including the gusts of wind blowing around as we approached.

We spoke to Brian, a machinist with 13 years. "The reason I voted to strike was the high profits they have made in the last three years. It's ridiculous that they try to off-load their costs onto us." In reference to the engineers and technicians union members crossing the picket line, he said, "It definitely works out to the company's advantage."

An aircraft electrician with 20 years at Boeing, Ron Strempel was picketing with his young daughter. We asked him what the most important issues were, as far as he was concerned. He explained, "My main issue would be job security. The company is offloading jobs. I'd like my daughter over there to have a job. But it's likely that she'll be working for some company that works for Boeing.

"So, that's one of the primary things, subcontracting. Boeing has made record profits, but the jobs are going. There are also takeaways on medical benefits and other smaller issues.

"Another thing is the pay for new hires and the pay grades. We have people starting at $12.37 an hour. That's only two bucks more than I made when I hired in 20 years ago. At that time, when you got the job you could afford to live. For the new hires, that's darn near poverty wages.

"The situation has changed. Boeing has trouble getting talented people, or training them. There's been a decline. When I hired in, a lot of people came out of the military, and they had experience. They get kids practically out of high school now, with no experience.

"I know a guy on a body structure crew. He has 5 or 6 people working with him that he won't trust. He's afraid of the damage. It's not their fault, it's a lack of experience."

Another worker put in that because of outsourcing, there were less than half the number of people working in tooling, his division. "And often the work has to be reworked."

Another worker put in that because of outsourcing, there were less than half the number of people working in tooling, his division. "And often the work has to be reworked."

We asked Strempel about the financial bailout and the growing crisis. Is any job safe under these conditions? "Well, all that hit the fan after we went out on strike. I was looking on the news for news about our strike, and I started noticing that all these banks were going down. I thought, maybe I should have been paying more attention. That's got me concerned. You'd think it's going to have some bearing on what happens to us.

"Still, they're going to need fuel-efficient airplanes. They're going to need the jets.

"But, I kid you not, the economic situation is worrying. It all started with these mortgages, but its spread."

He posed for a photo with his daughter.

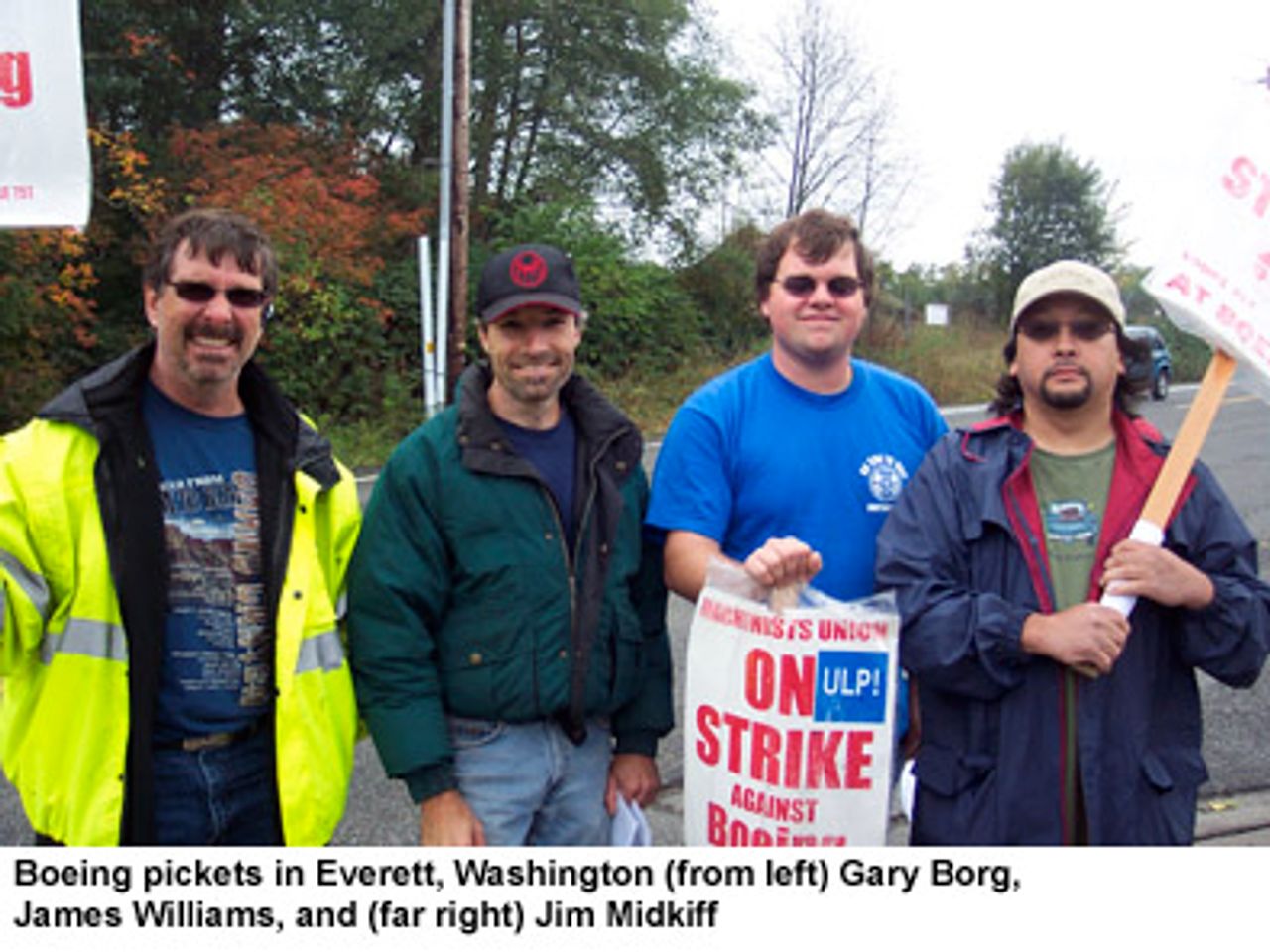

At a second location, three Boeing workers, Gary Bjorg, Jim Midkiff and James Williams, were on the picket line. We asked if we could discuss the issues in the strike with them, and they were kind enough to oblige. A wide-ranging discussion ensued, about the strike, the banking crisis, the elections and other issues, including the question of capitalism versus socialism. These are a few of the comments.

James Williams, currently an inspector, with 20 years at Boeing, spoke first about the immediate issues: outsourcing of jobs, the concessions the company is demanding on medical benefits, "higher deductibles, higher prescription costs, higher co-pays."

All the workers we spoke to were justifiably proud of the work they do, which is highly skilled and on whose thoroughness a great many lives depend. Williams said, "We make the best airplanes in the world. This company, unlike the auto companies in Detroit, is not down. They made $13 billion in the last six years."

Jim Midkiff put in, "It's flawed, the company approach. The business model is flawed."

Jim Midkiff put in, "It's flawed, the company approach. The business model is flawed."

Williams returned to the issue of Boeing's situation and the matter of concessions. "After 9/11, we offered certain concessions, until the situation settled down." We pointed out that we were opposed to concessions under any condition, that it wasn't the workers' fault if companies got into trouble. He acknowledged that, but still noted that Boeing wasn't in the same situation as the auto manufacturers.

Williams went on, "They have orders--they have a huge backload of orders. We're fighting for others, for labor. The starting wage hasn't gone up in 16 years. Unless you consider the cost-of-living, which doesn't keep up with things.

"I started at $10.42 in 1989. Now it's $12.72 20 years later. We have new hires, I've heard, who qualify for food stamps! I don't begrudge the CEOs and vice presidents what they make, but ...

"Politically, I'm disappointed in everything I see."

When we suggested that neither Barack Obama nor John McCain offered anything for the working population, no one disagreed.

Midkiff said, "People like to say that all the politicians are corrupt, all bad, they're all crooks, but I think this just lets them get away with things. They should be held accountable."

Williams added, "We've run a very profitable company. We make safe, reliable aircraft. I'm an inspector, when something slips by, it bugs me.

"They have a vice president of strategy at Boeing. I don't know what he does, he makes a lot of money. They are very vague in those titles, because the jobs are vague, they just make a lot of money."

Williams said he'd watched the stock market. He commented that in the period of 1985-95 there was a lot of talk about taking things âconservatively,' that in the auto industry they had promised more fuel efficiency and so on. But then after the early 1990s, "the stock market ripped. Ford built the Explorers and all those big boys, the SUVs. What happened to the âconservative model'?"

He went on. "Wages have not kept up with the cost of living in recent years. Yes, we've made a decent living, but we have overtime jammed down our throat, mandatory overtime. In 20 years I have worked 28 years with overtime. In 2007 the union machinists on strike right now worked something like 3.7 million hours of overtime. At least I can a house payment and feed my family, but they just keep taking away and taking away."

Williams, with the agreement of the others, noted the relative decline in Boeing workers' pay. Some years ago, at the beginning of the decade, "I was making 50 grand with overtime and a friend of mine, a mortgage broker in fact, was making $140,000." Williams implied that he had been better off at the time. He asked the others, "In the late 1980s, do you remember, the goal was to make $30,000?" He suggested someone could live on that at the time. Fifty thousand dollars today "is nothing."

Gary Bjorg, a flightline technician, explained he'd transferred from Long Beach in southern California just this January, after more than two decades. "We make the C-17 there." He'd started out when the plant was owned by McDonnell Douglas, which merged with Boeing in 1997. "We had 52,000 working there at one time; it went down to 2,500!"

The wind was really howling when we spoke to Toby Colvert and Rick Johnson at a third picket line in Everett. Seated in a folding chair, Colvert spoke about the concessions the company was demanding, diminishing retirement benefits and outsourcing. He noted that Dodge was now making everything in Mexico.

He pointed to a younger worker standing next to him, "He makes $14 an hour. How can you live on that? He can only do it because he lives with his family." We asked the younger guy how long he'd been working for Boeing. "I started a year ago," he explained.

Colvert continued, "We're too old to start fresh. We have mortgages and so on. If we were to retrench now, and pay out of our own pockets, we might as well be living in a trailer.

"There are lots of issues: retirement, medical benefits, outsourcing." He pointed to a nearby plant with the name "New Breed Logistics" on it. "That's one where jobs were outsourced. They make fasteners, I think, for Boeing. It's a vendor company.

Importantly, Colvert spoke with some feeling about the efforts by some to encourage animosity toward European workers at Airbus, Boeing's rival. The union bureaucracy plays a leading role in that.

Colvert said, "People criticize the Airbus workers. Why? They're just like us, trying to feed their families. There's no difference that I can see. Everybody wants to work, to make a decent living, the Airbus workers and us. Why should they be criticized?

"Executives make fortunes. The oil companies are making record profits. Everybody knows what's going on. And this bailout of the banks ... it's unacceptable." He noted that they'd put in clauses limiting executive pay in the bill passed by Congress. We suggested that none of that would be enforced, that the bailout was a huge theft of public funds to benefit the same people who had run the country into the ground. There was no disagreement from the strikers at any of the locations on that question.

Colvert went on, somewhat somberly, "Here at Boeing, we're just workers. We're very limited in what we can do. We're trying to preserve the jobs we have."

Colvert pointed to the existence of people living in tents in nearby Seattle. "It reminds me of the Grapes of Wrath." He mentioned Washington Mutual bank, which recently went bust. The institution, whose failure was the largest in US banking history, was headquartered in Seattle.

He noted that Boeing workers in Spokane, in eastern Washington, made $15 an hour, but that was considered very good there, because âIf you make $10 an hour in Spokane, that's considered a good wage."

We also spoke briefly to Rick Johnson, who had been listening to the conversation with Colvert. Johnson has worked for 30 years at Boeing, the most veteran worker we spoke to. He suggested that Boeing workers were "in a unique position," because of their skills. "Someone can cost the company $1 million with a slip of a drill. We're holding them hostage. It takes many, many years to train workers here."

We asked Johnson how many strikes he'd participated in during his three decades at Boeing. "Four," he replied. And the longest? "In 1989, 89 days." What about this one? "I think it's going to be a long strike."

Subscribe to the IWA-RFC Newsletter

Get email updates on workers’ struggles and a global perspective from the International Workers Alliance of Rank-and-File Committees.