This is the fifth and final in a series of articles on the recent Vancouver International Film Festival (September 25-October 10).

Every film that fails or disappoints does so in its own way. Pointing to the flaws of a work is not a pleasurable task. Some films are so far off the mark that there's not much to be said. Better to remain silent and hope the creators do better the next time or go into a different profession.

If a film can be encountered seriously, even if only in a sharply critical manner, generally that means it shows signs, or more than signs, of life. One recognizes a good intention, one important thought, a poetic moment, a performance, something. As with human beings, one looks for the best side, the potential, and encourages that. "If only he'd..."

Chinese director Jia Zhangke has made a number of intriguing films—including Xiao Wu, Platform, Unknown Pleasures and The World. He is immensely talented and capable of representing broader social situations, as well as very intimate and difficult personal dilemmas. Jia has shown a great concern for the fate of the Chinese population under the new economic conditions.

As he told me in a conversation in 2004, "The modernization in China brings a great many people from the provinces to work in the big cities. They sacrifice their lives in the service of this ‘modernization' in the great cities, which benefits other people. This is why this concerns me."

When his newest film, 24 City, was shown at the Cannes festival last May, he told a press conference there, "Since 2000, I have been wanting to make a film about how workers are affected by the transition from a planned economy to a market economy." Leaving aside the debatable notion that China ever experienced a genuinely planned economy, certainly not a socialist planned economy, Jia's intentions were no doubt worthy ones.

When his newest film, 24 City, was shown at the Cannes festival last May, he told a press conference there, "Since 2000, I have been wanting to make a film about how workers are affected by the transition from a planned economy to a market economy." Leaving aside the debatable notion that China ever experienced a genuinely planned economy, certainly not a socialist planned economy, Jia's intentions were no doubt worthy ones.

He was struck by the news that an old munitions factory in the city of Chengdu, known as Factory 420, which had made aviation engines for decades, was being torn down to make way for a new luxury apartment complex, 24 City. This became the basis of a film.

Jia explained, "The factory was going to be destroyed to put up all these luxury apartments and for me that change was highly symbolic of the speed with which change has been occurring in China."

The filmmaker conducted more than 100 interviews with former workers from the factory, before concluding that the film would be "richer and more emotional" if he added fictional elements. Hence the film contains five interviews with actual retired workers and four interviews with fictional characters played by actors, composites of certain characteristics that Jia and his co-screenwriter, Zhai Yongming, presumably wanted to portray.

Some of the material in 24 City is eloquent. The shots of the semi-deserted buildings, rain and broken windows, silent workers, a machine being loaded on to a truck.

The first former worker to be interviewed, He Xikun, talks about starting to work in the plant decades before. He reminisces about the camaraderie and about his old supervisor, Master Wang. We then meet the latter, now ancient and with his mental faculties failing.

Hou Lijun moved and started working at the factory in 1958; her first visit home didn't come until 1972. She speaks about being laid off at 41, and her subsequent job-hunting. "I tried and tried and didn't find one." She's retired, with little to live on; she does some sewing. "If you have something to do, you age more slowly."

The scenes with the retirees suggest decades of tedious labor, immense personal sacrifice, humility, dignity.

Then the fictional characters appear on screen. Hao Dali (Lu Liping), a Factory 420 worker also, who describes a long trip by boat and losing her son; Gu Minhua (Joan Chen), a beauty known as "Little Flower" in the munitions factory, who never found her true love and lives alone; Zhao Gang (Chen Jianbin), a television news presenter; and Su Na (Zhao Tao), who shops in Hong Kong for rich Chinese women and declares, "I want to make lots of money," so she can move her parents, workers, into the 24 City complex.

The fictional characters in general tend to be weaker, and not because a couple of them are less likable. Joan Chen is a talented actor, but she makes a poor Chinese worker. Her characterization borders on self-pity. Zhao Tao's character too is not entirely convincing. It's something of a caricature of a selfish Chinese nouveau riche, without a great deal of nuance.

The problem of presenting the working class truthfully is not merely an artistic one....

The film has fascinating moments and images, and even beautiful ones (for example: a girl in red on roller-skates on the roof of a building by a highway at dusk), but it fails to make a powerful emotional impact or penetrate very deeply.

Things are confused here, and the documentary/drama suffers. A lack of social and historical perspective lies at the heart of the problem.

Jia expresses sympathy for the workers and their families. That's all to the good. But it's not clear what his own attitude is toward the social phenomenon he's treating.

The old, isolated China, with its archaic factories and sclerotic bureaucracy, couldn't survive in the face of a globally integrated economy. But whether its direct insertion into the world economy would benefit the mass of the working population or enrich a handful of scoundrels at the top of society depended on a host of factors, external and internal. The problem in China today is not the result of modernization or globalization, but capitalism.

After all, it would not be too difficult to find leading figures in the Communist Party who might say, "Yes, China's modernization is a painful process, the suffering caused to people is regrettable and sometimes heartbreaking, but it's unavoidable and nothing can be done about it." Fatalistically, Jia tends to treat as a fait accompli a process that needs to be examined with immense care and precision, above all, in its historical context. He's overwhelmed, one feels, by the subject matter.

The combination of documentary and fiction causes certain difficulties, and it's not clear in this case whether the director and screenwriter helped themselves with its use, but more damaging is the confusion between social and natural facts of life.

People dying of old age or a love affair disintegrating produces one kind of sadness. Workers bullied or persecuted, an innocent man or woman executed, an uprising drowned in blood, produces another. The first type of tragedy, if one can term it that, is an inevitable part of life on our planet. Under any economic order, human existence and most relationships will remain finite. The second type is the product of humanity's still primitive social organization and is entirely remediable. Both avoidable and unavoidable tragedy belong in art's jurisdiction, but the artist needs to be clear what he or she is dealing with.

When Joan Chen's character speaks of her various, futile efforts to find love, what are we to make of it? Some of her difficulties seem to be the result of government policy, some to be the product of misfortune or her own errors in judgment. The overall effect is murky and not especially sympathetic.

Despite his intelligence and obvious film sense, Jia's passivity remains a problem.

The confusion of Chinese filmmakers and artists about the nature of Chinese society and history, as we've noted numerous times, is not their fault. Nowhere was genuine Marxism and left-wing thought more firmly suppressed than under the Stalinist regimes. They are at sea, to a large extent, when it comes to making sense of their own social reality.

Nonetheless, the spectator can't take that into account, so to speak, when watching a given film. That would be artificial and condescending. Either a film is successful as a coherent work of art or it's not. And Jia's most recent films, Still Life, Useless and 24 City, are not.

In 2004, in regard to one of Jia's films, I wrote: "One cannot help sensing that the difficulty in arriving at general conclusions about Chinese history and society has a bearing on the narrative approach of many of the Chinese and Taiwanese filmmakers. No doubt specific cultural traditions come into play, but the elliptical style, the deliberate fracturing of so many works into many small and apparently discrete dramatic units—cinematic non sequiturs, so to speak—may reflect in part this absence of an overall perspective. The filmmakers see individual fragments and moments of life in the region with astonishing clarity and even brilliance, but developing a comprehensive picture is more challenging."

And then in 2006: "The problem is large, the questions about the nature of the Chinese revolution and state are quite complex. Nonetheless, these great historical issues have to be approached. The artistic work suffers, even threatens to stagnate. It has been said before, but it bears repeating, that it's not possible to provide a significant picture, or even a smaller ‘slice of life' in the long run, without troubling oneself with social and artistic perspectives."

It's to be hoped that Jia, with his considerable artistic skills, will deepen his approach to social life.

Kazakh director Darezhan Omirbaev has made a loose film adaptation of Tolstoy's Anna Karenina, Chouga. Omirbaev has written and directed a number of serious films, Cardiogram (1995), Killer (1998) and The Road (2001). Killer, in particular, about a young man who falls into debt to gangsters and carries out an assassination of an investigative journalist to pay it off, was a sharp-eyed look at the new social types emerging in capitalist Kazakhstan.

In the new movie, Chouga (Ainur Turgambayeva) is a mother and wife, living in the new Kazakh capital of Astana. Her husband is a powerful and well-off politician. Meanwhile, the wealthy and arrogant Ablai (Aidos Sagatov) dallies with a young woman, Altynai (Ainur Sapargali), a student, the daughter of Chouga's affluent older brother. She has a suitor, a photographer, who truly loves her.

In the new movie, Chouga (Ainur Turgambayeva) is a mother and wife, living in the new Kazakh capital of Astana. Her husband is a powerful and well-off politician. Meanwhile, the wealthy and arrogant Ablai (Aidos Sagatov) dallies with a young woman, Altynai (Ainur Sapargali), a student, the daughter of Chouga's affluent older brother. She has a suitor, a photographer, who truly loves her.

Chouga and Ablai are introduced at a train station in Almaty and he becomes infatuated with her. He follows her later and declares his love, "I have to be where you are." His former girlfriend tries to kill herself. A friend tells him, "Do you care? You acted badly."

Ablai's feelings for Chouga become public knowledge, and her husband sends three thugs to beat him up. She stays the night with him: "That's it for me. All I have is you. Remember that."

She abandons her family, and the couple leaves for Paris. Ablai, however, is pretty much of a swine. He goes to strip clubs, leaving Chouga at home. She tells him, "I'm not jealous, but when you go to those places." Ablai has his gangster friends track down the men who attacked him and execute them; they send him a video of the gruesome event.

Chouga eventually recognizes who and what she's left her family for, and follows Anna Karenina's example.

The film is disappointing. No real emotion is generated by these characters, all of them privileged. Most of them are unpleasant (Ablai is thoroughly detestable), and Chouga is rather dull. Her descent into unhappiness and madness and her tragic end come, more or less, out of the blue. The story and its components are not developed adequately; everything takes place in a rush. Omirbaev seems to assume our sympathy and interest, rather than arouse and develop them.

It's true there are a great many long-winded and long-drawn-out films at present, but to do justice to the set of relationships under study in Chouga, and certainly Anna Karenina, requires more than 88 minutes. Events here are compressed in an impermissible manner. For example: early in the film, at the opera, Altynai, Ablai's girlfriend, sees him looking at Chouga from a distance. She storms out in a huff, and not too long afterward, attempts suicide.

And why is Chouga so unhappy in her marriage? We never hear a single complaint or witness any interaction with her husband. In fact, we only see him twice, briefly. Why should we be convinced of Chouga's inner torment? It's very unsatisfying, especially because Omirbaev (born 1958) has obvious gifts. Has the dreadful atmosphere in post-Soviet Kazakhstan defeated him?

Serbis is a new film from Filipino director Brillante Mendoza (Foster Child). An extended family operates a third-rate movie house, which shows soft-core pornography, in a provincial town. Tension, poverty, decay abound. The plumbing doesn't work. Male and transvestite prostitutes work in the theater. The matriarch of the family is suing her husband and awaiting the court decision. Her nephew plans to run out on his pregnant girlfriend. And so on.

Serbis is a new film from Filipino director Brillante Mendoza (Foster Child). An extended family operates a third-rate movie house, which shows soft-core pornography, in a provincial town. Tension, poverty, decay abound. The plumbing doesn't work. Male and transvestite prostitutes work in the theater. The matriarch of the family is suing her husband and awaiting the court decision. Her nephew plans to run out on his pregnant girlfriend. And so on.

There's some feeling for life here, but the fascination, or perhaps disgust, with its grosser aspects is troubling. The family operation seems to be a metaphor for Filipino society. "Our movie house is going bankrupt," "There's a lot to fix in this movie house," are among the less than subtle hints. If so, Mendoza's attitude toward his fellow countrymen and women seems to be less than sympathetic or understanding.

There's a concentration on the immediate and the detail, and the larger social picture is entirely missing, so one is irresistibly drawn to the conclusion that the rot of Filipino society is the fault of the ordinary Filipino. Not edifying, and not true.

Night and Day is the latest film by director Hong Sang-Soo (The Power of Kangwon Province, Woman is the Future of Man) about the failings of middle class South Korean men.

A painter, Kim, flees to Paris, afraid that he's going to be arrested in Seoul for possessing marijuana. He doesn't speak French, and he's left his wife behind in Korea. He meets an old girlfriend, then an art student and her roommate. He has dealings of one kind or another with all of them, while phoning his increasingly unhappy wife back in Seoul. The women are more or less interchangeable, which, one assumes, is the point of the criticism.

Night and Day takes the form of a journal, with entries over a two-month period. Hong is intelligent and some of the relations are well depicted, but, really, this is very slight. The director has cornered this particular market...and now should give it up. Perhaps life will suggest that to him.

The festival catalogue describes Liverpool, directed by Argentina's Lisandro Alonso (La Libertad), as "anti-dramatic, location-driven filmmaking." That sounds about right. In other words, there is virtually no dialogue, no interaction among the characters, but there are many shots of landscape.

The festival catalogue describes Liverpool, directed by Argentina's Lisandro Alonso (La Libertad), as "anti-dramatic, location-driven filmmaking." That sounds about right. In other words, there is virtually no dialogue, no interaction among the characters, but there are many shots of landscape.

A seaman, Farrel, leaves his ship in southern Argentina, having explained to the captain that his mother is sick and he needs to visit her. He travels to his hometown. En route, he stops at a café where a few people are playing cards. My notes read: "This passivity is encouraged by the critics. The scene, with nothing happening, goes on for minutes on end."

Farrel arrives home, and encounters his teenage daughter, whom, apparently, he's never met. She asks him for money. An older man berates him: "What are you doing here?... I don't know why you came back." Farrel goes to his mother's bedside. She doesn't recognize him.

Later, he gives his daughter a bracelet, and with "I'm off," leaves town again. That's more or less the film. A point is being made about Farrel's stifled nature and the non-relationships that go on within the Argentine population, but it's not much of a point. Alonso has a visual gift, but he needs to stop deluding himself that this cinematic "restraint" is anything but an evasion of reality's more complicated elements.

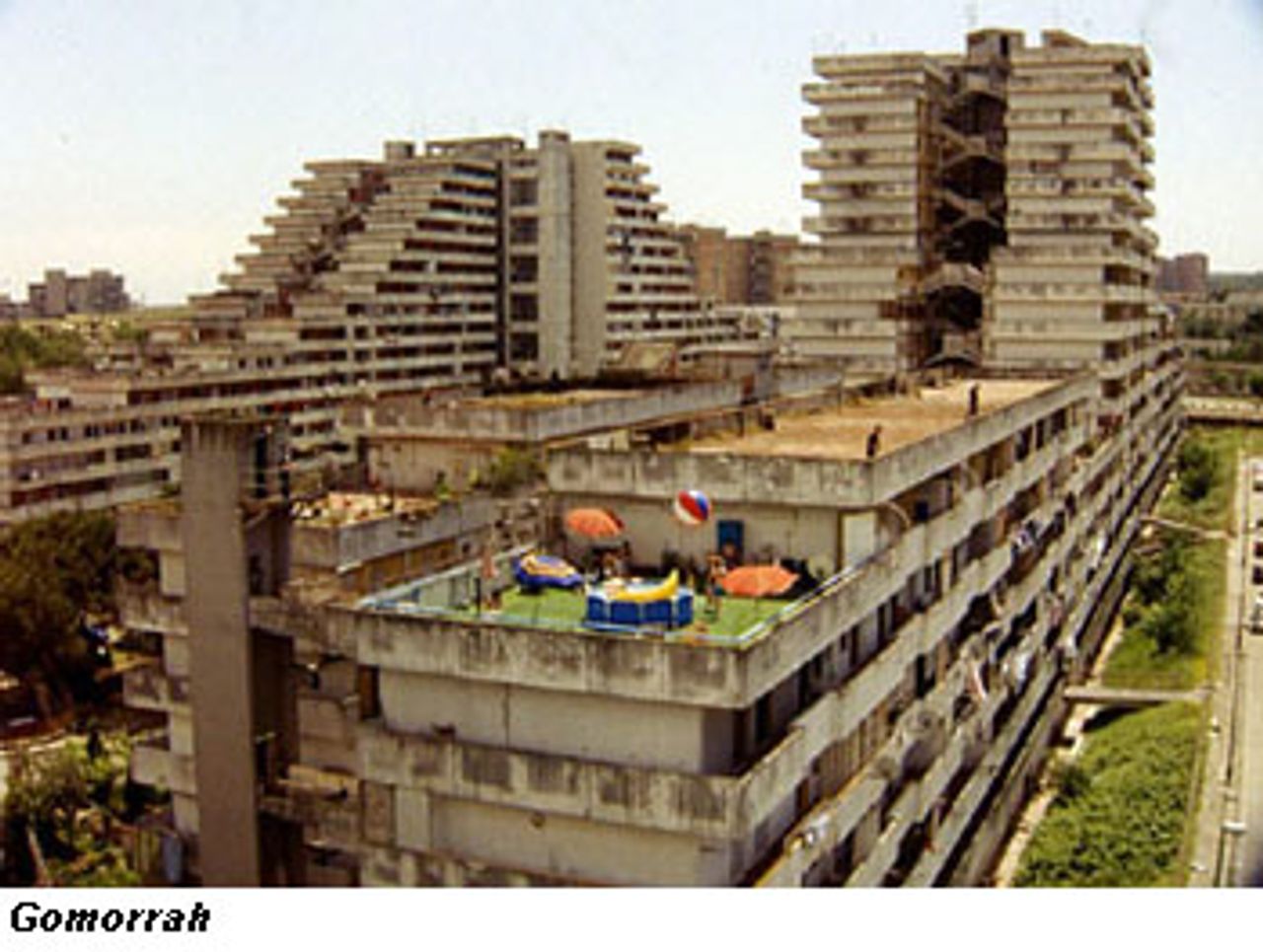

Gomorrah is an exposé of the Camorra, the crime organization operating in and around Naples, Italy. The fiction film takes place in Scampia, a suburb north of Naples, reputed to be the largest "open air" drug marketplace in the world. The film dramatizes events in 2004 when a war broke out within the Camorra, leading to dozens of deaths in a few weeks.

The film, written by Roberto Saviano and directed by Matteo Garrone, takes up five stories.

Don Ciro pays money to families who have relatives, crime outfit members, in prison. When the feud erupts, he has to figure out how to save his life. A couple of young lowlifes, Marco and Ciro, think that life is a gangster film; their disruptive activities get them in very hot water. Toto is a 13-year-old, eager to join the criminal clan.

The last two stories are the most interesting. A talented tailor, Pasquale, secretly accepts a job offer from Chinese rivals of the Camorra, risking his neck and other peoples' too. Roberto goes to work for Franco at a waste management company run by the mob. In the end, he can't stomach the burying of toxic waste, which is going to cost residents their health and perhaps their lives.

There are interesting sociological features here, but like most gangster films, Gomorrah gets much more caught up in the scenes of violence than is healthy. The film ends up, perhaps unwittingly, somewhat glamorizing the activity and individuals it means to criticize. Because, frankly, the filmmakers don't have a strong enough social point of view.

There are interesting sociological features here, but like most gangster films, Gomorrah gets much more caught up in the scenes of violence than is healthy. The film ends up, perhaps unwittingly, somewhat glamorizing the activity and individuals it means to criticize. Because, frankly, the filmmakers don't have a strong enough social point of view.

Garrone, the director, kids himself a bit along these lines. He writes, "The raw material I had to work with when shooting Gomorrah was so visually powerful that I merely filmed it in as straightforward a way as possible, as if I were a passerby who happened to find himself there by chance."

The material is as artificially organized, manipulated and rearranged as the material in any other fiction film. It's almost as though the director, upon seeing the final product, is saying, "I'm not responsible for this bloodbath, that's simply the way things are." He has a greater responsibility than that, like any artist, to make sense of and distance himself from his material, and not be dominated by it.

Concluded