We are republishing here the final part of a series of articles that originally appeared in April 1986 under the title “One hundred years since the Haymarket frame-up.” The articles were published in the Bulletin, the newspaper of the Workers League, forerunner of the Socialist Equality Party in the US.

The first part of this series was published on May 11; the second part on May 12.

A depiction of the conflict outside the McCormick Reaper Works on May 3, 1886, where several workers were killed by police.

A depiction of the conflict outside the McCormick Reaper Works on May 3, 1886, where several workers were killed by police.The ruling class was preparing for violence on the first May Day, but there was none. Instead, May 1,1886, was a historic culmination of the struggle for the eight-hour day.

More than 350,000 workers struck 11,562 establishments nationwide. In Chicago, 40,000 workers struck and another 45,000 were granted the eight-hour day without striking. Eighty thousand workers marched arm-in-arm down Michigan Avenue, led by Albert and Lucy Parsons and their children.

Above, on the rooftops, armed police and Pinkertons were in readiness, and detachments of the state militia, armed with Gatling guns, were holed up at the city armories.

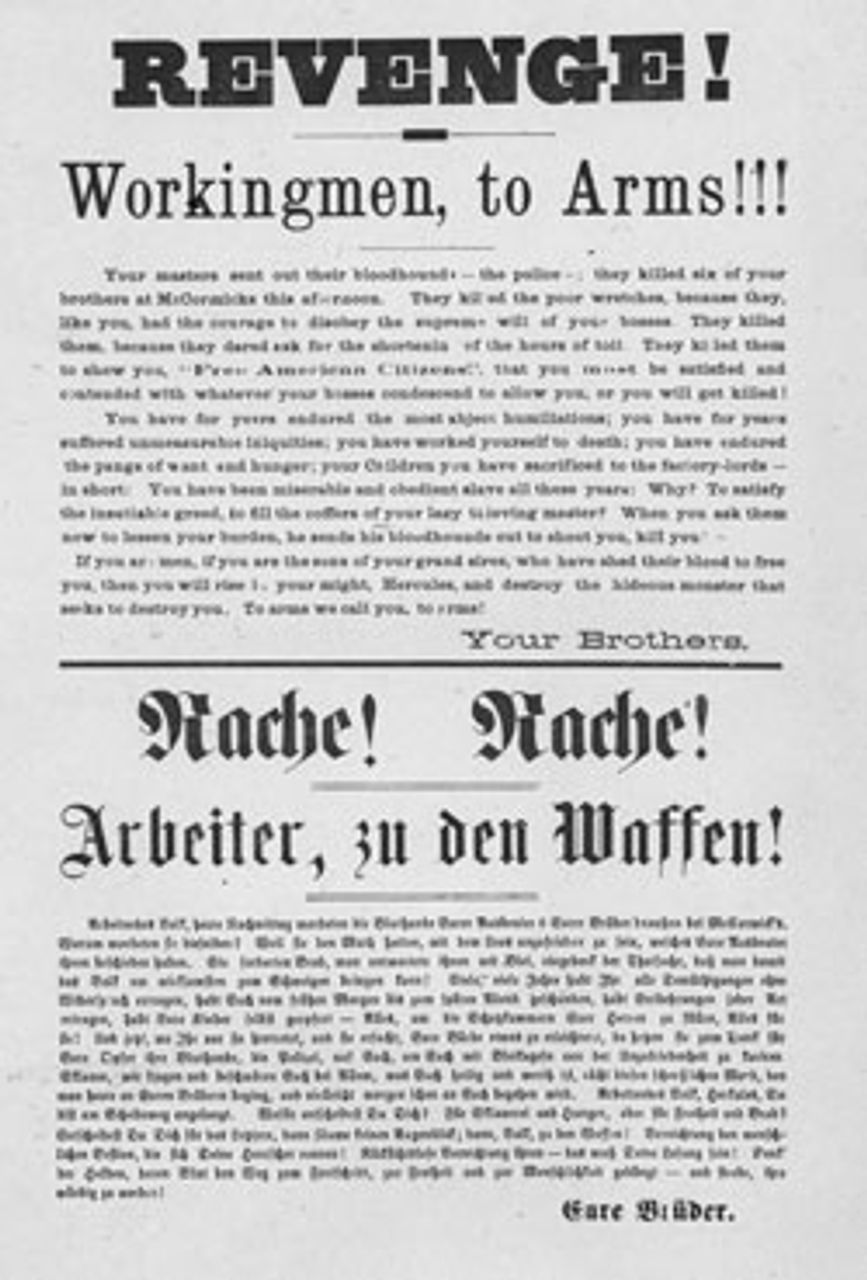

The infamous "revenge circular"

The infamous "revenge circular"After May Day the tension increased and then boiled over. On May 3 at the McCormick Reaper Works, several striking workers were killed by police following a confrontation with scabs. Outraged at the incident, August Spies issued a leaflet in German and English, in which the word “REVENGE,” in bold type, was added. It became known as the “Revenge Circular.”

“REVENGE! Workingmen, to arms!!! Your masters sent out their bloodhounds—the police; they killed six of your brothers at McCormicks this afternoon. They killed the poor wretches, because they, like you, had the courage to disobey the supreme will of your bosses. They killed them, because they dared ask for the shortening of the hours of toil. They killed them to show you, ‘Free American Citizens,’ that you must be satisfied and contented with whatever your bosses condescend to allow you, or you will get killed!

“You have for years endured the most abject humiliation; you have for years suffered immeasurable iniquities; you have worked yourself to death; you have endured the pangs of want and hunger; your Children you have sacrificed to the factory-lords—in short; You have been miserable and obedient slaves all these years. Why? To satisfy the insatiable greed, to fill the coffers of your lazy thieving masters? When you ask them now to lessen your burden, he sends his bloodhounds out to shoot you, kill you!

“If you are men, if you are the sons of your grand sires, who have shed their blood to free you, then you will rise in your might Hercules, and destroy this hideous monster that seeks to destroy you. To arms, we call you, to arms! YOUR BROTHERS.”

Only 2,500 copies of the leaflet were printed and less than half that number distributed, yet the “Revenge Circular” was used to implicate Spies in the Haymarket bombing. Meanwhile, at Grief’s Saloon, a meeting of anarchists was taking place that would later be referred to as the “Monday Night Conspiracy.”

Present at the meeting were two of the future Haymarket defendants, Adolph Fischer and George Engel, as well as other anarchists, mostly members of the radical North-West Side Group. These included Gustav Breitenfeld and Bernhard Schrade, commanders of the second company of Lehr-und-Wehr Verein (Education and Defense Society).

While the meeting was not called to discuss the Reaper Works shootings, it was agreed that a violent confrontation was imminent, and that the workers had to defend themselves against the bosses’ police. Thus it was decided that when the word “Ruhe,” meaning quiet or rest, appeared in the letter box of the Arbeiter-Zeitung, armed detachments of workers would assemble at various points in the city.

When the word “Ruhe” did mysteriously appear in the paper the next day, this was later used at the trial as “evidence” that the Haymarket defendants were preparing insurrection.

On May 3, Parsons had been in Cincinnati where he addressed an eight-hour rally and picnic. Arriving back in Chicago on the evening of the fourth, he spoke at the Haymarket meeting. Attending the early part of the rally was Mayor Carter Harrison, who, although regarded by some as a “friend of labor,” had warned that a call to violence by any of the speakers would result in the police breaking up the assembly.

Harrison later remarked that in the speeches of Spies and Parsons, “there was no suggestion made by either of the speakers for the immediate use of force or violence toward any person that night; if there had been I should have dispersed them at once.”

After addressing the crowd, Parsons waited at Zepf’s saloon nearby for the meeting to end. He was there with his family and Lizzie Holmes when they heard the explosion and the shooting, and saw people running for cover. They waited in a back room in darkness for the tumult to subside. Lizzie Holmes persuaded Parsons that he should leave the city for a few days. He took the midnight train to Geneva, a town forty miles west of Chicago, and the next day arrived at the home of his friend William Holmes.

The Haymarket incident whipped the ruling class into a frenzy. “NOW IT IS BLOOD,” screamed the headline of the Chicago Tribune on the day after the explosion. Spearheaded by the capitalist press, a vicious red scare and campaign of police terror was launched. The anarchists were vilified, the most vile invective reserved for those of foreign birth.

Joining the crusade against the anarchists was the leadership of the Knights of Labor. Terence Powderly, Grand Master Workman of the Order, frantically sought to disassociate himself from the anarchists. “Honest labor is not to be found in the ranks of those who march under the red flag of anarchy, which is the emblem of blood and destruction,” he declared. “It is the duty of every organization of working men in America to condemn the outrage committed in Chicago in the name of labor.’’

Meanwhile the police unleashed their reign of terror. “Make the raids first and look up the law afterward,” advised Julius S. Grinnell, the Cook County state’s attorney who was to prosecute the case against the anarchists.

The day after the bombing, Spies, Schwab and Fischer were arrested. Engel was arrested, released and then disappeared. Later it was learned that he had been picked up by police a second time and held incommunicado. Fielden was arrested at his home the morning of May 6, and Oscar Neebe, not until May 27. Only one of the future defendants arrested, young Louis Lingg, offered any resistance.

Paul Avrich, in his book, The Haymarket Tragedy, describes the reign of terror. “The police cast their dragnet far and wide. The next few weeks saw the detention of hundreds of men and women, most of them foreigners, who were put through the ‘third degree’ to extract information and confessions. Radicals were hunted ‘like wolves,’ wrote William Holmes, himself expecting arrest at any moment. Anyone suspected of the remotest connection with the IWPA was held for interrogation. Police headquarters and local precincts bulged with radicals of every type and with men and women who merely ‘looked like communists,’ reported the Chicago Times, including one because he spoke of Spies as a gentleman” (Avrich, The Haymarket Tragedy, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986, p. 221).

The campaign against the anarchists was backed financially by the Chicago robber barons, principally Marshall Field, Phillip Armour, George Pullman and Cyrus McCormick, Jr. The raids were conducted by the notorious Inspector John Bonfield and supervised by police Captain Michael J. Schaack. Schaack was a corpulent man, intoxicated with his own importance, who did everything in his power to keep up the anti-anarchist hysteria, even to the point of proposing the setting up of bogus organizations.

The bourgeois press howled for the speedy execution of the anarchists. A Chicago Times editorial stated, “Public justice demands that the European assassins, August Spies, Christopher (sic) Spies, Michael Schwab, and Sam Fielden, shall be tried, and hanged for murder. Public justice demands that the assassin A.R. Parsons, who is said to disgrace this country by having been born in it, shall be seized, tried and hanged for murder. Public justice demands that the negro woman who passes as the wife of the assassin Parsons, has been his assistant in his work of organized assassination, shall be seized, tried and hanged for murder. Public justice demands every ringleader of the association of assassins called Socialists, Central Union of Workingmen, or by whatever name, shall be arrested, convicted, and hanged as a participant murderer.”

Parsons was now a fugitive, and his wife Lucy was being daily hounded and tailed by police in the hope that she would lead them to him. At first Parsons did not know what had happened at Haymarket, and it was only the next day that he received news of the killings and mass arrests. He left Geneva and took refuge in Waukesha, Wisconsin, at the home of a socialist and subscriber to The Alarm, Daniel Hoan.

On May 27 a grand jury returned indictments against Parsons, Spies, Schwab, Fielden, Engel, Fischer, Neebe, Lingg and two other men, William Seliger and Rudolph Schnaubelt. Seliger, a member of the North-West Side Group, later turned state’s evidence, and Schnaubelt fled the country, ending up in Argentina where he lived out the rest of his life in anonymity. It was long afterwards believed that Schnaubelt was the “bomber.”

Parsons, meanwhile had effectively eluded capture. He kept up regular contact with his family and friends, but only William Holmes and Hoan knew his whereabouts. In Chicago, a Defense Committee had been established to collect funds and to secure legal counsel. The committee persuaded the prominent corporate lawyer William Perkins “Captain” Black to defend the anarchists.

Parsons remained at large for six weeks and could have escaped altogether. Yet he did not want to abandon his comrades and also felt confident that he would prove his innocence. Captain counseled that Parsons would get a fair trial and acquittal, despite the ferocity of the witch hunt.

Parsons carefully considered his decision. He later wrote, “I could see that the ruling class were wild with rage and fear against labor organizations. Ample means were offered me to carry me safely to distant parts of the earth, if I chose to go. I knew that the beastly howls against the Anarchists, for their bloody extermination, made by the press and pulpit, were merely a pretext of the ruling class to intimidate the growing power of organized labor in United States. I also perfectly understood the relentless hate and power of the class.”

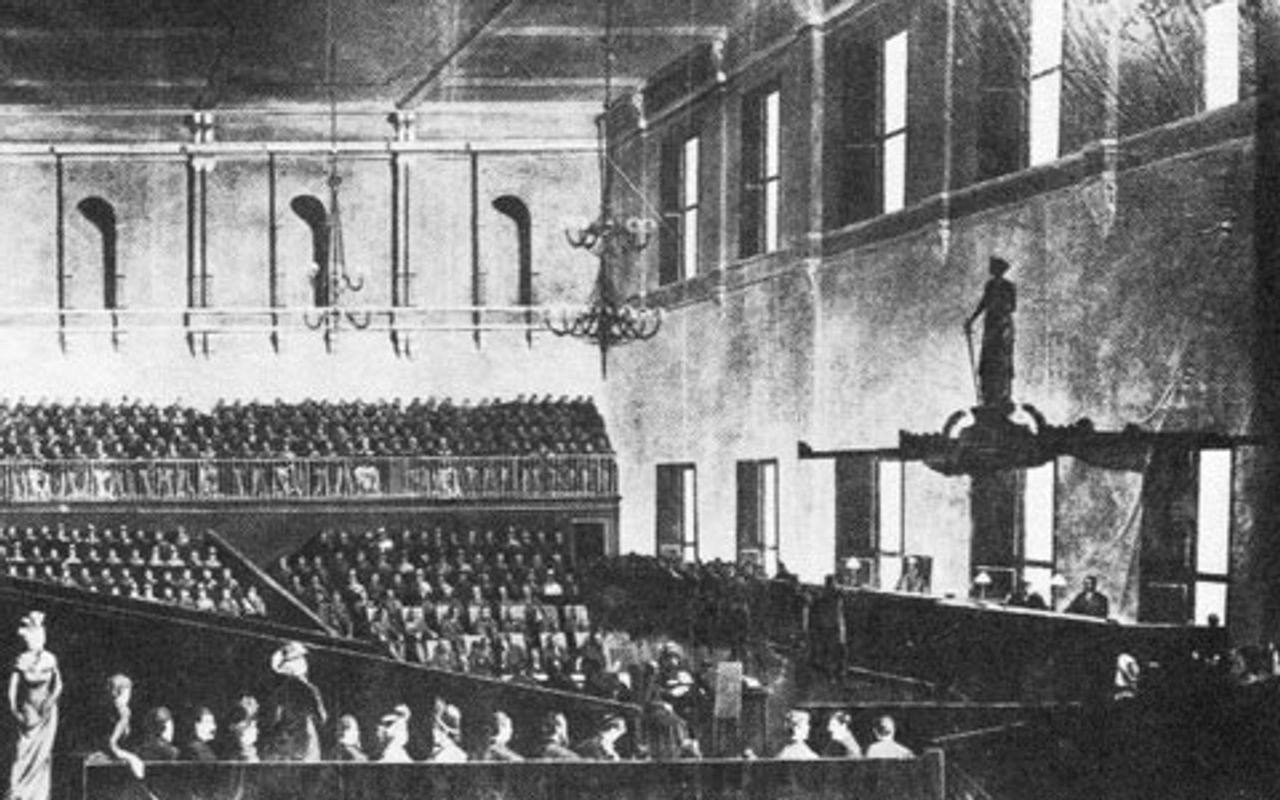

The Haymarket trial

The Haymarket trialOn June 21, Parsons, accompanied by Captain Black, entered Judge Joseph E. Gary’s courtroom. Parsons was instructed by the judge to be seated with the other prisoners. He shook hands with Spies and the others and was greeted warmly. Spies reportedly told Parsons he had placed his neck in the hangman’s noose.

The trial lasted from June 21 to August 20. Parson’s friend and fellow anarchist William Holmes wrote as trial opened, “Many of the comrades, and our lawyers are sanguine of an acquittal, but I confess I have great fears for the result.’’ Holmes fears were well-founded. Socialist and union leader Morris Hillquit later called the trial, “the grossest travesty of justice ever perpetrated in an American court.”

The outcome of the trial was, in fact, never in question. Although, the prosecution was unable to prove that the eight were guilty of murder or conspiracy to commit murder, the climate of hysteria maintained at a fever pitch by capitalist press enabled the state to convict the Haymarket defendants solely on the basis of their socialist and anarchist political beliefs.

The jury was selected through the usual random drawing, but handpicked by a special bailiff, Henry L. Ryce. This insured that the jury excluded anyone belonging to the Knights of Labor or any other workers organization, and accepted only those who were hostile to the anarchists and believed they should be executed.

In the course of the trial, Judge Gary ruled against the defense on every contested point. The judge showed utter contempt for the defendants. Cultivating a circus atmosphere at the trial, he surrounded himself with attractive, well-dressed young women who would giggle and eat candy during the proceedings.

The witnesses for the prosecution were a disreputable lot of paid liars, whose testimonies were repeatedly proven false. When it was established that none of the defendants had thrown the bomb, the state’s attorney Grinnel insisted, “Although perhaps none of these men personally threw the bomb, they each and all abetted, encouraged and advised the throwing of it and are therefore as guilty as the individual who in fact, threw it.”

In the case of defendant Louis Lingg, who defiantly paid no attention to the trial, even informant William Seliger failed to link him to the bombing, despite the established fact that Lingg had manufactured bombs.

In the end, however it was left to Judge Gary to instruct the jury before their deliberation. Seizing upon all in the printed statements in the Anarchist press, pamphlets like Johann Most’s “Revolutionary War Science,” Lucy Parsons’s “Appeal to tramps,” and other writings, Judge Gary ruled that if the defendants, “by print or speech advised, or encouraged the commission of murder, without designating time, place or occasion which it should be done, and in pursuance of, and induced by such advice and encouragement, murder was committed, then all of such conspirators are guilty of such murder, whether the person who perpetrated such murder can be identified or not.”

On August 20, after a brief deliberation by the jury the previous afternoon, the eight Haymarket defendants were found guilty. The verdict recommended the death penalty to all but Oscar Neebe, who should, according to the jury, be imprisoned for fifteen years. Of the defendants, defense attorney Black said, “not a face blanched, not an eye quailed, not a hand trembled.”

Parsons later observed, “The only fact established by proof as well as by our own admission, cheerfully given before the jury, was that we held opinions and preached a doctrine that is considered dangerous to the rascality and infamies of the privileged law-creating class, known as monopolists.”

At the sentencing in October, the defendants were given the opportunity to address the court. Their heroic speeches, imbued with an unshakable conviction in the ultimate victory of socialism, lasted for three days. Every defendant reasserted his innocence while denouncing the frame up nature of the trial.

Spies defiantly told the court, in his now famous words, “But if you think that by hanging us you can stamp out the labor movement—the movement from which the downtrodden millions, the millions who toil and live in want and misery, the wage slaves, expect salvation—if this is your opinion, then hang us! Here you will tread upon a spark, but here, and there, and behind you, and in front of you, and everywhere, the flames will blaze up. It is a subterranean fire. You cannot put it out. The ground is on fire upon which you stand.”

Louis Lingg, who appeared “like a caged tiger,” declared, “I do not recognize your law, jumbled together as it is by the nobodies of bygone centuries, and I do not recognize the decision of the court.... I despise you. I despise your order, your laws, your force-propped authority. Hang me for it.”

The seven anarchists were sentenced to hang on December 3, but the Defense Committee obtained a stay of execution in order to appeal the verdict. Now that the initial hysteria over the Haymarket bombing began to subside, support for the defendants began to build. Leading the fight to mobilize this support was Lucy Parsons, who spoke before more than 200,000 people during the campaign for leniency.

Lucy Parsons

Lucy ParsonsLucy Parsons, of Negro and American Indian background, never despaired, even after her husband’s execution, but instead rededicated her life to the struggles of the working class and oppressed. Along with Bill Haywood, Mother Jones and Eugene Debs, she attended the founding conference of the Industrial Workers of the World in 1905.

Lucy Parsons traveled the country for the next half century, fighting to clear Albert Parson’s name. After the Russian Revolution she worked with but never joined the Communist Party. A courageous fighter, she was a partisan of the working class to her last breath. On March 12, 1942, as she was approaching her ninetieth birthday, a wood stove in her home accidentally caught fire and burned her to death.

It took another six months for the State of Illinois to make its decision. The state denied the defense’s appeal. Then, on November 2, 1887, the US Supreme Court ruled that it had no jurisdiction in the case. Now the only recourse was to appeal to Governor Richard J. Oglesby for executive clemency.

With nine days left before the scheduled execution, pressure was placed upon the inmates to appeal for clemency. Oscar Neebe was now moved from Cook County Jail to Joliet to begin serving his 15-year sentence. Michael Schwab, Samuel Fielden and August Spies appealed for clemency, but Spies later withdrew his appeal. Parsons, and the three more radical anarchists, Engel, Fischer and Lingg, refused to appeal for clemency.

Parsons issued an “Appeal to the People of America” in which he expressed his readiness to die. All four anarchists demanded unconditional release from prison or death.

During the whole period of their imprisonment the conservative leaders of the Knights of Labor and the newly formed American Federation of Labor refused to defend the anarchists. It was only when their execution appeared impossible to postpone, that Samuel Gompers personally appealed to Governor Oglesby for clemency. Gompers feared that the execution of the anarchists “would place a halo of martyrdom around them which would lead many to the violent agitation we so much deplore. In the interest of the cause of labor and peaceful methods of improving the conditions of achieving the final emancipation of labor, I am opposed to this execution. It would be a blot on the escutcheon of our country.” Gompers’s belated appeal was too little too late.

On Thursday, November 10, the day before the executions, Louis Lingg took his own life with a dynamite charge smuggled into his cell by fellow anarchist Dyer Lum. Several hours after reports of Lingg’s death reached Springfield, the Illinois state capital, Governor Oglesby commuted the sentences of Schwab and Fielden.

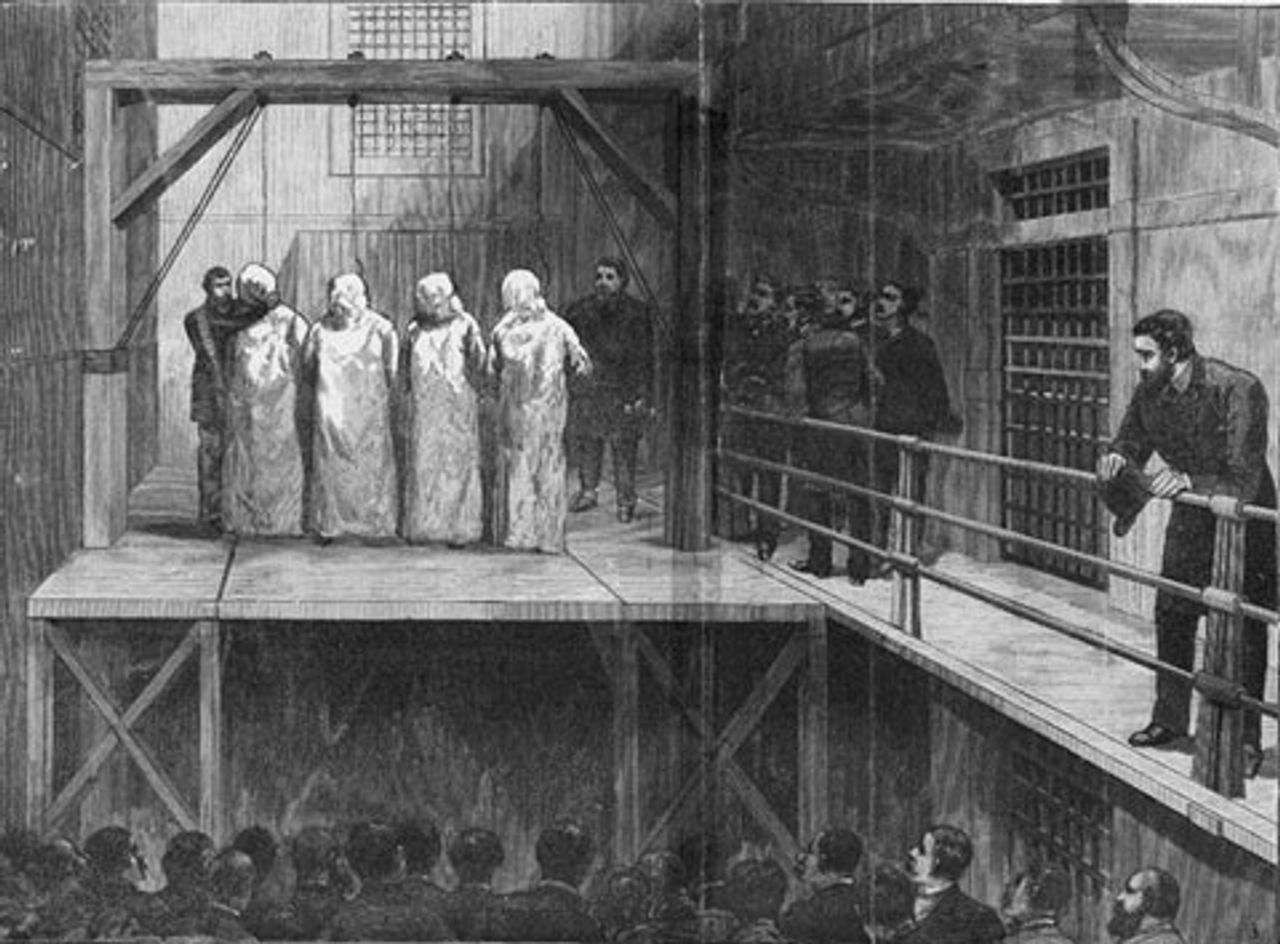

The hanging on "Black Friday"

The hanging on "Black Friday"At 11:30 a.m. on the morning of November 11, “Black Friday,” Albert Parsons, August Spies, Adolph Fischer and George Engel were led to the scaffold. Paul Avrich describes the scene: “The witnesses stopped talking when they heard the sound of feet on the iron stairway. One after another the prisoners appeared, each guarded by a deputy. Spies at the head, erect and firm, stepped to his place on the scaffold and turned towards the spectators.

“Close behind came Fischer, his chest thrust out, his bearing dignified, to all appearances unconcerned. Glaring at the crowd, he planted himself on the spot assigned to him, threw his head back and waited. Engel looked absolutely happy. His face showed no absence of color, and his eyes twinkled. Parsons, by contrast, wore an abstract look, as if his mind were on something else quite remote from the business at hand.” The ropes were placed around their necks and the shrouds were fastened. “The time will come when our silence will be more powerful than the voices you strangle today,” declared Spies with his final breath. At 12:06 the four men were pronounced dead. Upon examining the bodies, doctors at the scene revealed that the necks of none of the four anarchists had been broken. All four had died slowly of strangulation (Avrich, The Haymarket Tragedy,p. 392).

On June 36, 1893, seven years after Haymarket, Illinois Governor John Peter Altgeld pardoned Samuel Fielden, Michael Schwab and Oscar Neebe.

On the 100th Anniversary of Haymarket, the Workers League pays tribute to these towering figures in the history of the American and world proletariat. Today, under conditions of an unprecedented capitalist crisis and new developments in the class struggle worldwide, we rededicate ourselves, on the 100th May Day, to the building of the International Committee of the Fourth International, the Trotskyist movement, world party of the socialist revolution.

Concluded