SLL Pamphlet: Reformism on the Clyde:

SLL Pamphlet: Reformism on the Clyde:The story of UCS

The following article was published by the Socialist Labour League, the forerunner of the Socialist Equality Party in Britain, as an appendix to Reformism on the Clyde, by Stephen Johns, published by Plough Press in 1973.

The analysis in the pamphlet was drawn together from contemporary articles published in the Workers Press, the SLL’s newspaper, with which the SLL intervened in the shipyards against the Stalinist union leaders James Reid and Jimmy Airlie.

“… A significant personality in Scottish affairs … a compelling orator, an expert negotiator and an organiser of supreme skill … a man of great intelligence and drive and massive ability and determination … also a friend of mine”—Description of James Reid in the ultra-Tory Scottish Daily Express.

James Reid, leader of the work-in at Upper Clyde Shipbuilders, is the most remarkable product of modern Stalinism. He is the first member of the British Communist Party to win approval from the entire capitalist class. Praise ranges from the ultra-right wing Scottish Daily Express—which describes him as the “big swarthy communist who exudes the warmth of a teddy bear … a formidable leader of men who is mainly responsible for keeping all four Clyde yards working, to the ‘liberal’ Guardian, which is impressed by his lack of revolutionary fervour and says it’s a shame he’s not a Labour MP.

The television has been equally solicitous. There have been Reid profiles, Reid discussions on programmes like “Late Night Line Up” with ‘live’ confrontation shows with Reid in the studio audience. A far, far, cry from the Clydesiders of old like John Maclean, who was jailed for his agitation during times of crisis and industrial unrest in Glasgow.

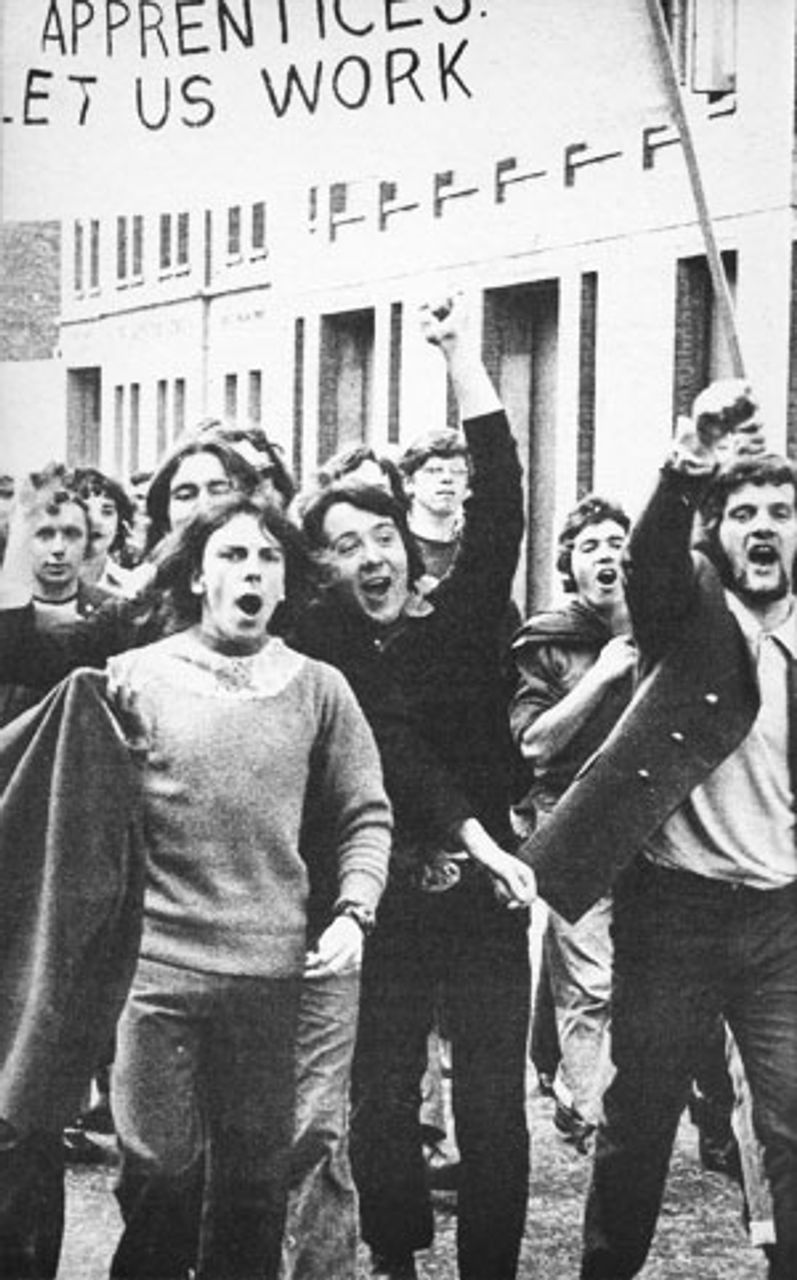

Shipyard apprentices protest

Shipyard apprentices protestNot for Reid the wrath that descended on these socialists. Instead, this 40-year-old member of the Communist Party’s national executive is welcomed as some new type of workers’ leader. The media like his style and philosophy.

The attraction is not difficult to fathom. The moral bromides that Reid preaches on the television, or from the Rectorial pulpit at Glasgow University, are the quintessence of reaction.

The essence of Reid’s philosophy—if it can be called that—is to view society in abstract and make a plea for certain moral and structural reforms.

He said, for example, on a recent ITV profile: “I want advancement and technology. I want all those things but I want it associated with certain moral principles and precepts—not abstractions—that say, “Your role in life is to develop your talents to the full in the service of human beings”—out of the rat race and into the human race. Because we are part of the human race, aren’t we?”

Clergymen welcome this appeal. One Plymouth vicar even suggested in the letter columns of the Guardian that Reid was speaking for the ‘Holy Ghost’. Their support is not surprising.

Reid borrows platitudes of Christianity and attempts to weave them into his vision of the good life. He attempts to bring down religion from heaven and give to it new vigour by making it ‘secular’.

In his interview to the Scottish Daily Express he was quite specific about this. He was asked what were the major influences in his life.

“For a start” replied Reid, “I am interested in the social teaching of Christ, as expressed in the Sermon on the Mount and the Beatitudes [blessed are the poor for they shall see God]. They amount to a social ethic to which I subscribe.”

“Yes I am a Christian. I believe that Christianity, like all major religions, can only last on the basis of its humanism—with a small ‘h’ of course.”

Here in a crude fashion Reid echoes the German idealist philosopher Feuerbach, against whom Marx developed his profound ideas on dialectical materialism.

Like Reid, Feuerbach brought God to earth. He developed a materialist approach and argued that man’s thoughts—including those of God—had to be explained from the world in which he lives.

But he conceived man as an abstract being inhabiting an equally abstract natural surrounding. He ignored that man lived, produced and thought under certain social conditions—capitalism, feudalism, slavery, and so on.

Because of this, Feuerbach developed an abstract outlook, materialist in its foundation, but one which viewed man as he should be according to the universal and timeless nature of his species, rather than how he was under certain conditions of class oppression.

The effect of such reasoning is to replace the need for revolutionary change with a reformist desire to alter society to correspond to certain ‘moral’ principles that reflect man’s ‘true’ nature.

Of course, it would be ludicrous to suggest that Reid is the intellectual equal to Feuerbach or that he had made any independent contribution to philosophy. Feuerbach’s writings were an important breakthrough towards a full dialectical materialist outlook on life. Reid is merely one of the more extreme examples of the intellectual and moral bankruptcy of Stalinism. Nevertheless, the core of Reid’s reaction is based on crude idealism. His outlook is all the more potent and dangerous since it is the foundation of his politics and strategy at Upper Clyde Shipbuilders, as we shall see.

Lenin launched an attack on this kind of God building and un-historic outlook in the socialist movement.

In a letter to the Russian writer Maxim Gorky he took issue with those like Reid who try to ‘socialize’ God and religion. These kind of ideas, he wrote, “go out among the masses and [their] significance is determined not by your good wishes, but by the relationship of objective social forces, the objective relationship of classes.”

“By virtue of that relationship it turns out [irrespective of your will and independently of your consciousness] that you have put a good colour and sugary coating on the idea of the clericals … in practice the idea of God helps them to keep the people in slavery. By beautifying the idea of God, you have beautified the chains with which they fetter ignorant workers and peasants.”

The words could be applied to Reid, but with one big difference.

Reid does not eulogize the teachings of Christ to create a ‘people’s religion’, but as part of the Communist Party’s own drive to snuggle up to the ‘progressive’ churchmen and the middle class. Indeed Reid, throughout the UCS struggle, continually praised and featured the support of the church in the fight for the right to work.

It is in the more popular Communist Party literature one can find the origins of Reid’s reflections.

Maurice Cornforth, the Oxford academic and Party member, laid out the foundations of the Party’s appeal to the middle class in his Marxism and Linguistic Philosophy, which is popularized in a CP pamphlet by him called Communism and Human Values.

His section on religion is a particularly instructive insight into modern Stalinist ‘theory’.

He argues that religion derives from the alienation and depersonalization of men in communities that have passed beyond the stage of primitive techniques. Hence religion is a phenomenon of human consciousness.

But he conveniently fails to explain that though religion is a reflection of a specific human condition, it itself enters into class relations as the ruling class use it to oppress the masses and justify their rule.

The omission leaves Cornforth open to suggesting that religion is some ideology of the masses that can be used in the fight against oppression.

This is the philosophical brief for men like Reid who go ahead and argue that religion can be progressive. But once again the mistake of Feuerbach is repeated. The role of religion must be examined in its specific social context—in this case, under the utterly decadent system of capitalism.

Lenin in the Gorky letter labelled this approach as bourgeois because “it operates with sweeping general ‘Robinson Crusoe’ conceptions in general, and not with definite classes in a definite historic epoch.”

He says “God is … first of all a complex of ideas generated by the brutish subjection of man both by external nature and by the class yoke—ideas which consolidate that subjection, lull to sleep the class struggle. There was a time in history when, in spite of such an origin and such a real meaning of the idea of God, the struggle of democracy and the proletariat went on in the form of a struggle of one religious idea against another.”

“But that time too, is long past”

“Nowadays, both in Europe and in Russia, any, even the most refined and best intentioned defence or justification of the idea of God is a justification of reaction”.

One might add that even when the masses fought wars against the ruling class beneath the banner of religion there was an uneasy alliance between the naïve materialism and religion. Hence the Levellers in the 1640s wanted the rule of the Saints on earth, but they also developed a crude theory about the exploitation of labour by man, which was un-Godly.

This critical analysis is perhaps to credit Reid with a more developed philosophical position than he has got. Suffice to say his moral gleanings, from Cornforth, the modern Stalinist writers and the New Testament, serve his reactionary supposition that capitalist society can be ‘restructured’ to make life better for ‘the people.’

He made this quite explicit in his Rectorial address to the students of Glasgow University.

He chose as his topic alienation, which he described as Britain’s major social problem.

Alienation was “the cry of men who feel themselves the victims of blind economic forces beyond their control. It’s the frustrations of the ordinary people excluded from the process of decision-making. The feeling of despair and hopelessness that pervades people who feel with justification that they have no real say in … determining their destinies.”

The remedy was to “root out anything and everything that distorts and de-values human relationships.”

At the end of his speech he suggests how this can be achieved:

“Given the creative … re-orientation of society, there is no doubt in my mind that in a few years we could eradicate in our country the scourge of poverty, the underprivileged, slums and insecurity.”

“A necessary part of this must be the restructuring of the institutions of government and, where necessary, the evolution of additional structures, so as to involve the people in the decision-making process of our society. To unleash the latent potential of our people requires that we give them responsibility.”

This could be one of those fine speeches by the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Duke of Edinburgh or even a Tory. After all, we are all against the “rat race” and it would be nice if the ordinary bloke got a bit more say in things—make him feel wanted.

It is noticeable that the ‘communist’ Reid censored all mention of capitalism, the working class, revolutionary change and socialism.

(One note of caution, these quotes are taken from a lengthy extract of the Rectorial address in the Glasgow Herald.)

His purpose again is to suggest that capitalism can be adapted (‘restructured’) to remove the social evil of alienation. This is in fundamental opposition to the facts. The root of the mistake lies in his incorrect description of alienation.

Reid describes here the concept of alienation beloved of the bourgeois-sociologist and the trendy vicar.

Alienation is not man’s inability to take part in decision-making, but something far more fundamental. It comes from the productive relationships of capitalism.

A worker is alienated from the things he produced because from the outset it is the property of the capitalist employer.

Equally he is alienated from his labour—which is also the employer’s possession—and this leads to alienation from production itself.

Production becomes a means to satisfy a need and not a natural process or a need itself.

Since it is man’s deepest need to produce and create, what is truly human in man is made animal—for the capitalist a worker might as well be a horse.

This digression is important. Reid’s idealist and semi-religious concept of alienation leads him right on to suggest that alienation can be removed if society were only restructured or reformed along certain moral guidelines (i.e., the social teachings of Christ).

But far from being a bad aspect, alienation is the essence of capitalist society. It can only disappear when capitalist production relations are replaced by socialism.

Reid’s mistake is deliberate. He preaches an abstract view of society and garnishes this with a few middle-brow observations on the rat race in order to hide the necessity of a revolutionary overthrow of capitalism by the working class as the only solution of the crisis of humanity.

It is only when these reactionary and idealist concepts are applied to the class struggle on the Clyde and against the government that the full range of Reid’s treachery is exposed.

At face value some of his statements about the Tories are astounding.

Take one example from the Scottish Daily Express interview:

“If we end up with four yards and the distinct probability of a modern shipbuilding industry on the Clyde, I think the government, and the Ministers involved, will have shown a courage and objectivity which is to be welcomed.

“Although we have our point of view about should have been done a year ago, I will say to the government, ‘Well done’.”

This kind of abysmal praise for a government that has driven 15 percent of the men in his hometown onto the dole is, however, only an extension of his ‘philosophy’ to industry and the class struggle.

He sees the Tory government, for example, as a group of individuals who are obsessed with the outdated philosophy of 19th century capitalism.

These Tories ought to respect modern needs of society—which are to help people live useful and creative lives.

Of course the argument is reactionary rubbish; there is nothing outdated about the Tory attempt to drive down living standards and keep up profits through mass unemployment.

The effect, however, is to disarm the working class since the corollary of these views is that employers and Tories can see the error of their ways and alter industry for the benefit of society.

At least this was what Reid suggested when he discussed the future of the upper Clyde yards on ITV.

The interviewer noted that Clyde had a history of decline—was Reid optimistic about the future?

“Well my point is this, I am hoping in the two companies that emerge that sufficient [knowledge] will be learned from recent experiences to show that the structure of the company will allow the latent talents of the workforce to express themselves.”

This is Reid’s prescription for alienation, taken out of the university and into the shipyards. The result is remarkable. This kind of attitude bears a very close resemblance to corporatism. Basic antagonism between workers and capitalists, like Marathon Manufacturers and Govan Shipbuilders, are resolved in some overall scheme for industry. With a bit more say in the ‘decision making process’ creativity will flower in the yard labour force; the industry will prosper and everyone will share the benefit.

These arguments are embodied in the Marathon deal signed by Reid and the other stewards. The deal is corporate in philosophy with provisions for absorbing the trade union structure into a mutual system of arbitration. The assumption is that independent struggle by workers is ‘unnecessary’ and can be eliminated in favour of the mutual benefit between employer and workers, to be derived by joint effort.

This kind of fool’s paradise promoted by Reid completely contradicts the facts. The two companies on the Clyde will face the most intense international competition. Govan will operate in a completely depressed market for shipbuilding. Both companies will launch a vicious campaign to drive up productivity and break down all the protective practices among the yard workers.

Reid’s claptrap about ‘releasing latent energies’ in fact echoes the propaganda put out by employers’ organizations like ‘Working Together’—an outfit motivated by the extreme right-wing ‘Aims of Industry’.

Workers must regard this kind of squalid moralizing. Capitalism is, always was and always will be the enemy of the workers. Its very existence depends on exploitation of the working class—it will not change it spots.

Like the God-builders, Reid pours a sugar coating over capitalism. He does it in a period when the class war in Britain is reaching a bitter climax—this is why the press and television love James Reid.

He does talk of socialism—the ballot box variety, of course. But, according to the Guardian, “talk of revolution irritates him.” With Reid the struggle for the workers’ state is always relegated to some dim and distant future. In practice he leads campaigns which divert workers into a Tory trap.

Hence his hatred of workers in the yards who criticize him from the left. These people, he says, are so far to the left “by Einstein’s theory of relativity they must be going over to the right.”

This is a revival of the old Stalinist war cry that the left-wing opponents of Stalinism in the 1930s were ‘fascist agents’—fortunately modern Stalinism has no longer the power, the credibility or the courage to repeat the slander openly.

Yet ‘sensitive’ men like Reid, who care so much for the quality of human life, find it no problem to remain in the Stalinist movement. Reid argues that much of what he dislikes in Russia, the purges and the persecution of intellectuals, is a product of ‘Russian tradition and history’.

This saves him the political embarrassment of condemning the Stalinist regime that flourishes like a cancer on Russian society.

It is this regime that is responsible for the oppression and the purges, the dishonesty and the lies. If it is otherwise, Reid presumably believes that socialism ‘Russian style’ can exist side by side with barbarism. This is a shocking slander of socialism, which is a negation of all inhumanity and exploitation, deceit and barbarism.

Reid is indeed a man of his time. He is a product of Stalinism that raised him to full political maturity.

But workers should remember it is in the idealism, ‘religion’ and moralizing that weeds of Reid’s reaction flourish.

There has always been a great radical tradition in Scotland.

But its hallmark was always a refusal to fight for a dialectical materialist outlook on life. The offspring of that tradition stalks the Clyde today in the form of James Reid and many of the lesser Communist Party leaders.

Workers in or around the revolutionary movement may turn away in disgust from the politics of Reid. But let them look to their own theoretical development—the road to treachery is paved with good, ‘moral’ intentions.

Fill out the form to be contacted by someone from the WSWS in your area about getting involved.