The TUC 2010 annual congress

The TUC 2010 annual congress

The Trades Union Congress (TUC) held its annual congress this week in Manchester, England, the city where it was founded 142 years ago. It decided, after due deliberation and ceremony, to do precisely nothing about the savage programme of austerity measures that the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition government is set on imposing.

The congress proposed no concrete course of action, no protests and certainly no strikes by any of its 6.2 million members, in response to the most devastating package of public spending cuts seen in Britain.

Instead the TUC accorded a warm welcome to Mervyn King, governor of the Bank of England, who has insisted that the cuts must be introduced as quickly as possible. Following the election, King warned Prime Minister David Cameron and Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg that unless they announced immediate austerity measures there would be a run on the pound.

There could be no delay in implementing a deficit-reduction programme, or the financial markets would turn against Britain as they had done against Greece. “The bigger risk at present, given the experience of the last two weeks, would be for a new government not to put in place clear and credible measures to deal with the fiscal deficit,” King told the coalition leaders.

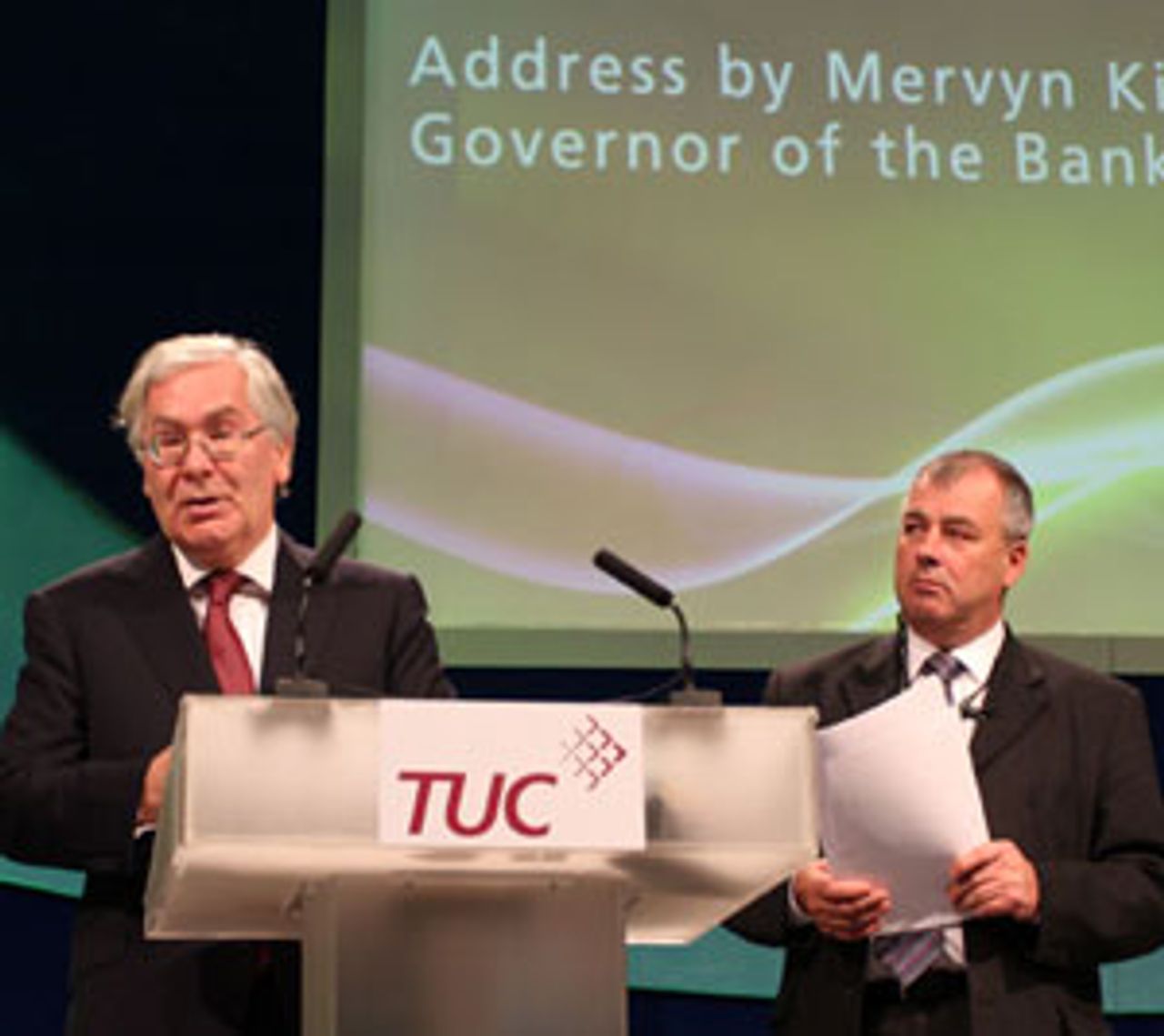

Mervyn King left and TUC General Secretary Brendan

Mervyn King left and TUC General Secretary Brendan

Barber during question and answer session

The man welcomed by the TUC is one of the chief architects of the government’s austerity programme. King told the delegates assembled at Manchester, “We at the Bank of England and you in the trade union movement should work together. That is why I am pleased to be with you today.”

He was pleased to be there and the TUC was pleased to have him. But reports in the media gave an entirely different impression. The Daily Mail warned, “Unions vow to halt UK with strikes”.

Rupert Murdoch’s the Sun claimed, “Union leaders are meeting to draw up plans for the biggest strike action the country has seen in decades, in protest at public spending cuts... Britain is teetering on the brink of an Autumn of Discontent”.

King was “entering the lion’s den,” said the Herald.

John Monks

John Monks

The media’s attempt to present the TUC as an organisation about to unleash massive opposition to the government was rudely punctured by the performance of its leaders. John Monks told the congress, “Let me say that I believe that influence on the boardroom will be better than influence on the picket line as a guide to trade union strategy in the future.”

Monks, general secretary of the TUC from 1993-2003, was speaking at the TUC congress for the last time in his capacity as leader of the European Trades Union Confederation. He will shortly become Lord Monks and take up a seat in the House of Lords, following in the footsteps of many previous trade union bureaucrats. When he was still leader of the TUC, in 1997, the Financial Times reported that he told incoming Labour Party Prime Minister Tony Blair, “The days when trade unions provided an adversarial opposition force are past in industry”.

His successor, Brendan Barber, would endorse every word. He has been a member of Court of the Bank of England since 2003. King had come to address colleagues, not adversaries.

“I want first to thank you for inviting me to address Congress.” King said, “Members of your General Council have made a huge contribution to the Bank of England by serving on our board—the Bank’s Court.”

He thanked Barber personally for “bringing a distinct and important perspective to our discussions, Brendan has helped us through some extremely turbulent times. I am grateful to him.”

The tasks of the Court are “to manage the Bank’s affairs other than the formulation of monetary policy ... This includes determining the Bank’s objectives and strategy, ensuring the effective discharge of the Bank’s functions, ensuring the most efficient use of the Bank’s resources and to review the Bank’s strategy in relation to the Financial Stability Objective.”

This means that Barber has been intimately involved in determining the strategy of the Bank of England in the period of gross financial speculation that led to the credit crunch and the present economic crisis. When King issued his warning to the incoming coalition government and told them that they must cut public spending fast and hard, Barber had already been part of discussions on financial stability. He is continuing to stand by King in “turbulent times” and the rest of the trade union movement is doing the same.

The TUC proposed not a single day of industrial action. Instead they agreed to a “lobby of delegates and fringe meetings at the Liberal Democrat and Conservative conferences” in September and a rally in Westminster on 19 October, on the eve of the government’s Comprehensive Spending Review. In March of next year, 11 months after the coalition government first came to office, there may be a “national demonstration”.

Even King seemed surprised by the TUC’s muted response. “I understand the strength of feeling,” he said. “In fact I am surprised it has not been expressed more deeply.”

The refusal of the unions to mount any struggle against the attacks was summed up in a pre-congress article in the Guardian, which stated, “Barber feels Britain is in a phoney war, and that this is the moment to marshall arguments”.

“At present it is a theoretical debate and the government can point to poll ratings showing public support,” Barber told the Guardian, “but once people begin to see the impact, and reality dawns, I think there will be a real reaction”.

The reality is that the coalition government is already fighting a very bitter and real war against working people. Immediately on assuming office they announced £6 billion in spending cuts. Cuts of between 25 and 40 percent are to be implemented across all government departments. Earlier this month Chancellor George Osborne announced that £4 billion in welfare spending cuts would be detailed in October on top of the £11 billion already planned for the spending review. More than 1.2 million jobs will be lost as a result of these austerity measures.

There is nothing phoney about these cuts. It is the TUC’s opposition that is phoney. The trade unions are determined to ensure that this unprecedented attack goes unchallenged. Since the coalition came to power in May, the unions have organised just one strike—one-day action on the London Underground against job losses.

As for talk of the trade unions mounting a “Winter of Discontent”, in a Guardian comment on Tuesday, TUC deputy general secretary Frances O’Grady wrote, “Of course, the media has mainly been interested in possible strikes.” But she promised the ruling class that, whereas “some difficult disputes are to be expected ... this is not going to be a re-run of the famous winter of discontent: 1979, at least as it entered popular mythology, represented a point of rupture between trade unions, particularly those in the public sector, and the wider community.”

The “winter of discontent” referred to by O’Grady was in fact a period of intensive industrial conflict that followed several years of struggles by the working class against huge attacks from a Labour government. The TUC remained throughout this period the main prop of Labour and consistently supported Labour’s measures. It was Labour and the TUC that allowed the most right-wing government seen to that point in Britain, the Conservative regime of Margaret Thatcher, to come to power. With the exception of the miners’ strike of 1984-85, which the TUC disowned and isolated, the unions have not led a single serious struggle over the three decades since.

By the 1990s, the average number of working days lost to strikes each year was just 660,000, with 1998 recording the lowest ever figure of 235,000 in just 205 stoppages, compared with 1,221 in 1984. During this period trade union membership in Britain has more than halved and is now down to 6.14 million, compared with between 12 million and 13 million in 1979. In the private sector only around 15 percent of workers now belong to a union. Last year Unite, Britain’s largest union, saw its membership fall by more than 83,000. The CWU postal workers union reported a decline in membership of 30,000 last year and has lost more than 50,000 members since 2007.

The TUC has reached such a moribund state that it is incapable of mounting even a token show of opposition to the coalition government’s austerity measures. The starting point for any struggle to defend jobs, wages and conditions is for workers to recognise that the unions serve as tools of the ruling elite. In the TUC and its affiliated unions, the working class confronts an enemy just as vicious as the corporate bosses and the big business politicians.

Fill out the form to be contacted by someone from the WSWS in your area about getting involved.