Britain is back in recession. According to the Office for National Statistics (ONS), the economy shrank by 0.2 percent over the first three months of 2012, following a 0.3 percent contraction at the end of 2011. It has now entered a double-dip recession, the first since the 1970s.

The British economy has flat-lined, showing zero growth over 12 months, joining euro zone members Greece, Portugal, Slovenia, Italy, the Netherlands, Belgium and Spain in an official recession.

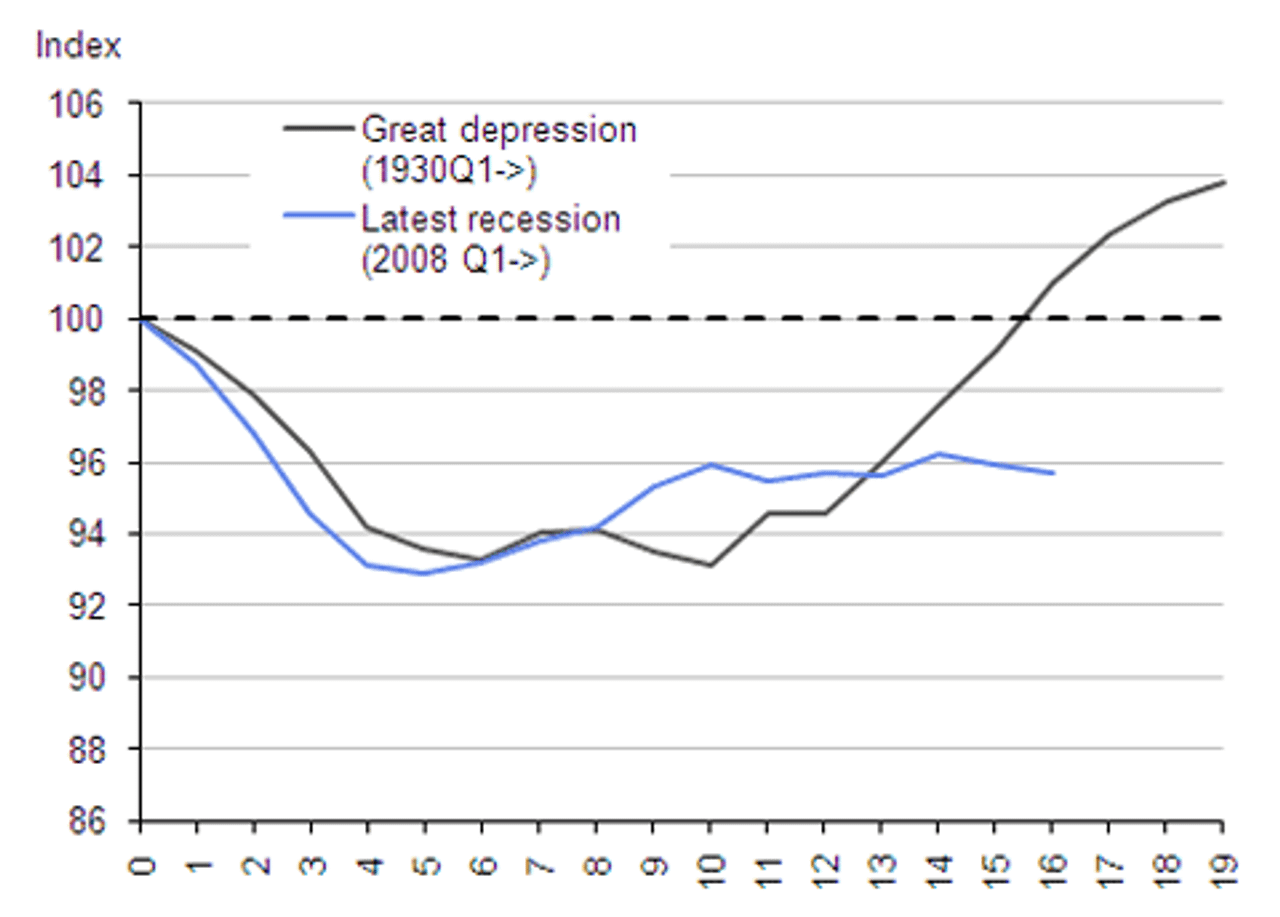

Commenting on the figures, the ONS states, “The economy is weaker relative to its pre-recession peak than at the corresponding stage of the depression in the early 1930s”.

The dire situation of the British economy is made even clearer in their accompanying graphic (see below).

This view is shared by other finance experts. According to Michael Saunders, an economist at Citigroup, Britain is experiencing “the deepest recession and weakest recovery for 100 years”.

This view is shared by other finance experts. According to Michael Saunders, an economist at Citigroup, Britain is experiencing “the deepest recession and weakest recovery for 100 years”.

The economy has only recovered less than half the output lost in the 2008-2009 recession, and four of the last six quarters have shown negative growth. Production was down in January and February, and is 3 percent lower than the same time in 2011. The ONS points to the “weakness of the global economy, especially the euro zone,” as the main factors impacting negatively on the UK.

The service sector, which accounts for three quarters of output, has only seen “modest growth”, with three of its four main sub-sectors contracting in January and February. Business and financial services—towering over all other service sub-sectors—contracted in February, recording only 0.1 percent growth over the quarter.

The situation would have been worse without the contrived “fuel crisis” sparking panic buying in March and bumping up petrol sales by 4.9 percent.

Construction has contracted by nearly 5 percent, continuing a downward trend since 2010 when the sector briefly returned to positive growth after crumpling following the 2008 crash. This has impacted on the economy as a whole, beyond the immediate size of the sector that currently employs some 2 million, down from a peak of 2.37 million in 2008. Despite a dire shortage of accommodation for families and singles on average and low incomes, house building fell in 2011, as did other areas of construction hit by the government’s squeeze on public sector capital projects.

British exports are down, particularly to the euro zone. The United States, Britain’s biggest single country export market, accounts for almost half of the fall in exports to non-EU countries.

For workers, the experience of the last year has been of growing poverty and hardship. Wages and salaries have fallen again, as the annual rate of earnings growth of 1.1 percent was less than half the rate of inflation at 3.5 percent. This is an underestimation, as it is calculated using the government’s favoured Consumer Prices Index that usually produces a lower figure. The situation of those on lower incomes is much worse, as relatively greater spending on food, fuel and other basic necessities skews inflation upward for those at the bottom.

A study by ONS, “The impact of the recession on household income, expenditure and saving”, finds that the financial crisis and recession of 2008-2009 and poor economic situation since then have had “a significant impact on the financial position of households”.

Figures show that while food prices have risen continually since 2008, the volume of food and non-alcoholic beverages purchased has fallen. This is no surprise given that since 2009, five out of eight quarters have seen a decline in real household disposable income.

This is already translating into growing malnutrition, particularly among children. According to a recent study by youth charity The Prince’s Trust, half of secondary school teachers surveyed regularly encounter pupils suffering from malnutrition, with some admitting they frequently buy food for struggling pupils from their own wages.

Official unemployment has fallen marginally over the year. But this masks the fact that while part-time working (at minimum or just above minimum wage) has risen, the number in full-time work has dropped. Longer term unemployment, those out of work for 12 months or more, has increased.

The government blames the euro crisis for the return of the recession, which is “dragging down” the British economy. Prime Minister David Cameron’s response was that it must be made easier for business to employ people in Britain. What this means is that wages and social costs should be pushed down even further, and sacking people made easier through abolishing already minimal employment protection rights in the name of labour market “flexibility”.

Chancellor George Osborne was adamant that the government must maintain its austerity measures so that Britain does not lose its AAA credit rating.

For the Labour Party, Shadow Chancellor Ed Balls claims that the consensus is changing across Europe, away from spending cuts. But in reality Labour agrees with imposing the burden of the crisis onto the backs of working people—as can be seen up and down the country in Labour-controlled local authorities, where workers have been sacked and much needed services cut.

In January, Labour leader Ed Miliband pledged that a Labour government would adhere to “tough new fiscal rules”. For his part, Ed Balls has refused to promise to reverse the government’s public spending cuts. Speaking on Newsnight at the end of last year, he said the government was cutting “too far and too fast” but that Labour had to be “realistic” when dealing with the economic crisis.

One thing is certain: the cuts are only just beginning. In its 2010 Spending Review, the Conservative-Liberal Democrat government announced proposals to cut public spending by £81 billion by 2014-15. Ninety percent of these cuts—£77 billion—have yet to come into effect.

In addition, the Centre for Economics and Business Research has calculated that the onset of double-dip recession will leave the government facing a black hole in its budget of £170 billion between now and 2016-17, based on present cuts in spending. This is being used in order to argue for further cuts.

Fill out the form to be contacted by someone from the WSWS in your area about getting involved.