The bodies of the four missing miners who had been trapped underground following Monday’s explosion at the Upper Big Branch mine in southern West Virginia were found by rescue teams early Saturday morning. This brings the total of miners killed in the blast to 29, making it the worst coal mine disaster in the US in 40 years.

Funeral services were held Friday for three of the miners killed in the Montcoal, West Virginia explosion. The mine, operated by Massey Energy Company, had received hundreds of safety violation notices in the weeks leading up to the blast. (See “Miners doomed by collusion between regulators and coal companies”)

State Troopers at the funeral of Deward Scott

State Troopers at the funeral of Deward ScottHundreds of people attended funeral services Friday for Benny Willingham, 61, from Corinne, West Virginia, and Deward Scott, 58, from Montcoal. Benny had worked in the mines for 30 years, the last 17 working for Massey. He was five weeks away from retirement when he died. Deward had been a miner for 21 years. A viewing was held on Friday evening for Jason Matthew Adkins, 25.

On Friday afternoon, rescue teams began a fourth attempt to enter the mine and to reach the final safety chamber after previous attempts had failed due to hazardous conditions.

The bodies of seven of the 25 victims were removed on Monday before rescue teams were forced to evacuate the mine for fear of a second explosion.

Meanwhile more information has come to light from workers about the horrendous conditions in Massey’s mines.

Josh Napper, a 25-year-old coal miner killed in the blast, had left his family a letter saying he was afraid to go back to work, and that he would be “looking down on them from heaven” if anything happened to him. His family said the mine had been shut down on April 2 because of high methane gas levels.

Massey workers and contractors interviewed by the World Socialist Web Site echoed these sentiments, saying the company had a horrendous safety record.

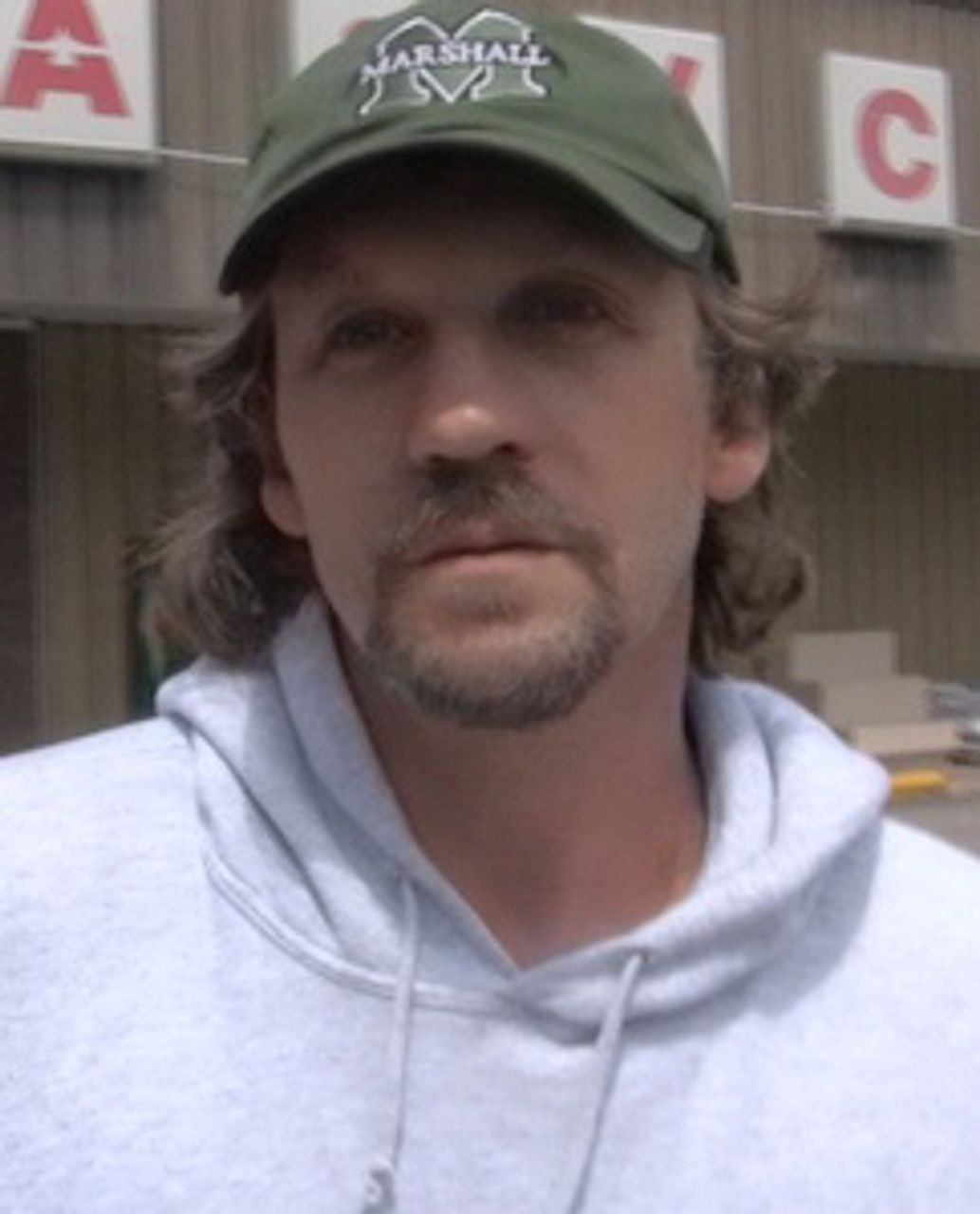

Dale Moore

Dale MooreDale Moore, a former contract miner for Massey, said he was not surprised that workers at the Upper Big Branch mine had been working in an area with deadly gas levels. He said that he and fellow miners had been forced to work in mines where their spotters—small devices that monitor gas levels—showed potentially explosive conditions. He would not say explicitly whether or not the mine was run by Massey.

“One time I was in a crew going down to a deep mine. Every member of the crew had their spotter go off when the elevator doors opened. But the company said not to worry about it, and that the battery chargers must have been bad.” Moore said that he and his coworkers proceeded to finish their shift. “What choice did we have?”

A portion of the Upper Big Branch Mine

A portion of the Upper Big Branch Mine“Other times, I have been dropped off at a face, two miles from the nearest phone,” Dale said. “They would leave me with no way out of there, and they would tell me that they would pick me up when my shift was done. ”

“I was a carpenter for 17 years. I had to work out of state to earn enough to live. You can’t make any money around here as a carpenter—maybe nine dollars an hour. That is not enough to live on. When I came back, I started working in the mines. Massey wouldn’t hire me because I had health issues, and they didn’t want to give me any insurance, so I worked for one of their contractors instead.”

“Working for Massey is like being a slave,” he said. “You have to do whatever the company says, you have no rights. It’s even worse if you’re a contractor for them; then you don’t even get insurance.”

Moore said that one time the company had his crew work a single shift of 22.5 hours after a roof collapse broke an underground conveyor belt. “They did not even bring us any food or water; they just wanted the coal moved.”

He said the miners were powerless to do anything about it. “It is not right to work men like that; but what could we do? If you complain, you get fired.” Moore said that his father, a coal miner, died in a roof collapse in a mine run by Swamp Fox Development.

The view from the hill overlooking the portal where

The view from the hill overlooking the portal where rescuers have entered the Upper Big Branch mine

A current Massey miner said, “For Massey, it is cheaper for them to pay the fines than it is to fix problems. They just figure—why spend the money to protect the men when there will be others that can work for them?” He did not give his name because he was afraid of losing his job.

Kelly Lowe, a coal miner’s wife, said that mining was the only decent job available in the area. But she added that Massey had recently made the workers pay for 20 percent of their health care instead of 10 and cut their pay. Despite that, the miners were still working 10- to 12-hour shifts.

“My grandfather, father, uncles, brothers, cousins—they are all coal miners,” Kelly said. “It is a dangerous job. If you have a family, there is only one way to take care of them here; it means going into the mines. If you don’t work in the mine, then you don’t have anything.”

“I would beg my husband every day not to go into the mines if that were not the only way he could provide for us,” she said.

Subscribe to the IWA-RFC Newsletter

Get email updates on workers’ struggles and a global perspective from the International Workers Alliance of Rank-and-File Committees.