Rescue teams reentered the Upper Big Branch Mine in West Virginia early Monday morning hoping to remove the nine remaining bodies of the 29 miners that were killed in last Monday’s blast.

Early Saturday morning rescuers found the bodies of four missing miners. On Sunday, teams seeking to recover bodies were forced to leave the mine after encountering high levels of methane gas. Crews worked during the night to ventilate the mine through several boreholes.

The Upper Big Branch Mine is owned by Massey Energy, the 5th largest mining company in the United States. The disaster last Monday was the deadliest coal mining accident since a 1970 explosion in Hyden, Kentucky that killed 38 miners.

Public pressure is growing for the Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) to hold a public investigation into this disaster.

Already a huge body of evidence has emerged that justifies the criminal prosecution of Massey CEO Don Blankenship and other top officials at Massey Energy. In addition, evidence exists that top MSHA officials are also criminally responsible for failing to carry out their responsibility to ensure miners’ safety.

MSHA records reveal that over the past several months company officials at the Upper Big Branch Mine were engaged in a dispute with regulators over serious ventilation problems. In December of last year, mine safety officials cited Massey for disregarding a previous order to redirect dirty air that was coming off a conveyor belt tunnel away from the area where miners were working.

In March 2010, safety officials found that Massey still had not corrected the problem. In addition, they found that airflow was half of what was needed to prevent the buildup of explosive methane gas and coal dust.

On Friday, MSHA officials released data showing that the Upper Big Branch Mine was cited five times more often than the national average for ventilation and coal dust control problems. In fact, MSHA investigators had ordered the mine or parts of it closed 61 times since 2009, including seven times this year because of unsafe conditions. However, MSHA officials took no action to have the mine shut entirely.

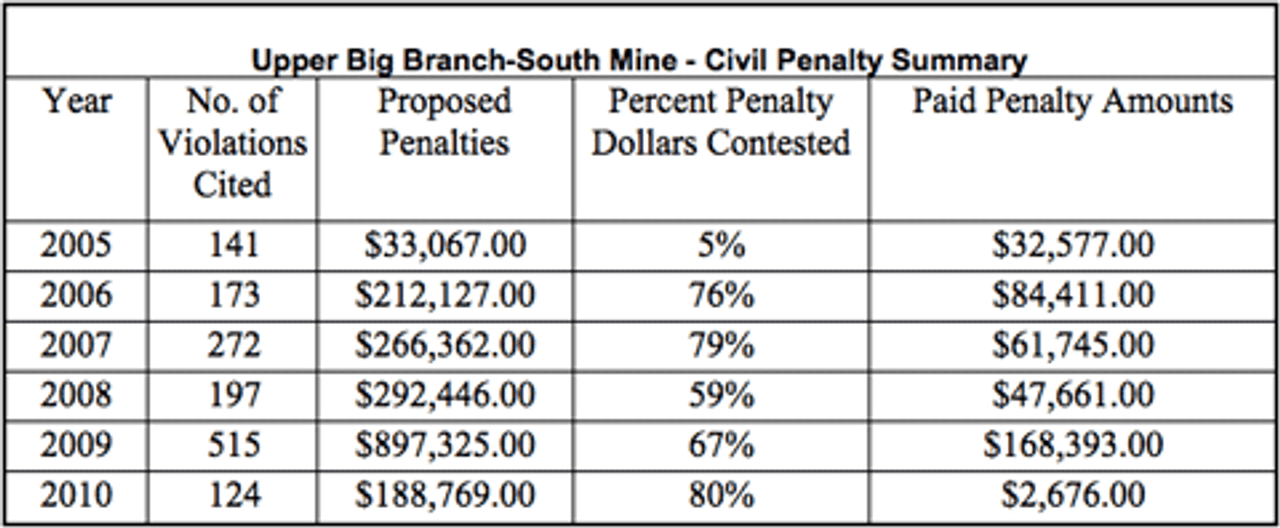

Since 2006, when MSHA began a somewhat more aggressive inspections and citations policy following the Sago mine disaster, Massey Energy officials carried out a deliberate policy of challenging citations. The aim was to bury the small number of Labor Department judges under a pile of appeals.

More important to Massey than not having to pay the small fines was the fact that an appealed citation would not be considered when establishing a “pattern of violations” that could lead to the mine being closed down.

MSHA records show that company officials at the Upper Big Branch mine began appealing citations issued by safety officials to prevent a “pattern of violations” from emerging

MSHA records show that company officials at the Upper Big Branch mine began appealing citations issued by safety officials to prevent a “pattern of violations” from emergingThis practice is not limited to the Upper Big Branch Mine or even Massey Energy. Government records show that every major coal producer has instituted the same policy.

The World Socialist Web Site spoke to workers and residents in West Virginia about the mine disaster and the conditions that led up to it.

Kelly, who works in a local store, said, “Mining is not a career choice. If you live in this area, mining is the only job around. If you are not working at Massey or one of the other few mines in the area, there is not very much else that you can do that pays enough to support a family. These men are working because this is how to get by. These men have no other choice.

“I do disagree with how things work at Massey. These state and federal inspectors go into these mines, and they are able to continue operating unsafe.”

“Massey makes a killing in these mines, and then it is big news that they announce they will pay for the funerals,” Kelly added. “What is it going to do for these families who have lost husbands, fathers and sons that the company will pay for the funeral?”

Denny, with his coworker Sherry

Denny, with his coworker SherryDenny, 19, said, “I feel that if there were not so many safety violations, the situation would be a whole lot different. I hear a lot of people talking about Massey and I can’t think of a good thing that anybody has said about them.

“There are no jobs in a little spot like this except the coal mines. I have to drive all the way to Charleston every day for a job that is not in the mines.

“It is basically mines if you want to make money to support a family. The only future I see here are the coal companies. Even the railroads depend on coal. The company doesn’t care about the miners, just about the money.”

Chuck Smith is a laid-off miner with seven years working underground. “Massey doesn’t care about the miners, just getting that coal out. They have a slurry pond in the mountain right above an elementary school. What is going to happen to those children if the dam breaks? A few years ago, they were mining in the mountain under the slurry pond and accidentally punched into it and had all that water and mud flooding into the mine.

“When I started as a miner, I was working for a contractor in a Massey mine. There was a cave-in, and they brought us in to clean it out. The miners told us it wasn’t safe. When we got done, instead of giving us all jobs, they sent us home. We fixed the mine up and were laid off the next day. I’ll never work for Massey again.

“My friend went in and worked the long wall [at Upper Big Branch]. He said the whole face was falling and breaking all the time. He came out and said there was going to be a cave-in in that mine. If you could look at the company records, you would see that in the last three months lots of people quit that mine because they knew it wasn’t safe.”

Subscribe to the IWA-RFC Newsletter

Get email updates on workers’ struggles and a global perspective from the International Workers Alliance of Rank-and-File Committees.