Dmitri Shostakovich wrote two operas while he was still in his 20s, and rarely came back to the form during the rest of his life. The Nose, completed in 1928 before he was 22 years old, has just received its New York Metropolitan Opera premiere. Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, written a few years later and first produced in 1934, was presented at the Met 10 years ago.

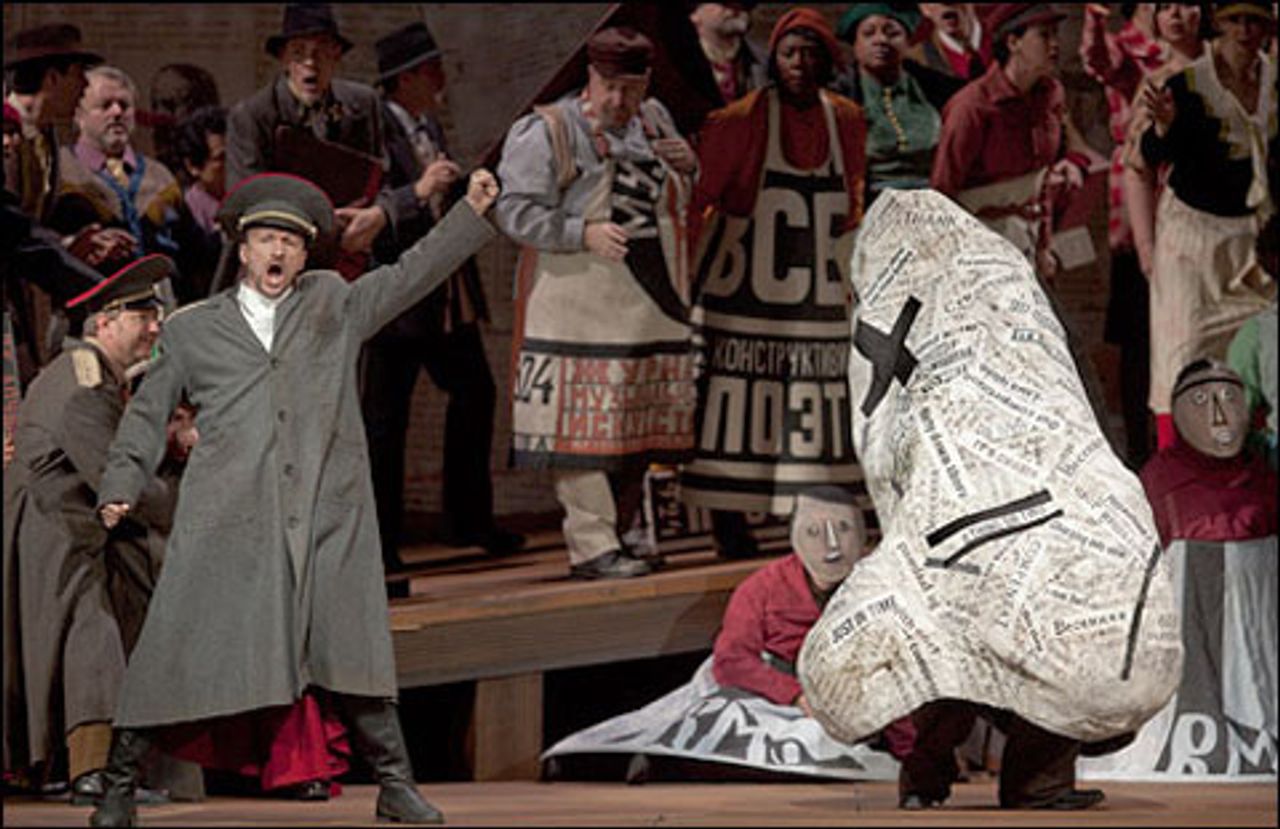

The Nose – Photo: Ken Howard

The Nose – Photo: Ken HowardBoth works are based on 19th century Russian literature, the first on the famous Nikolai Gogol short story (1836) and the second on a novel by Nikolai Leskov (1865). These are important sources; the Gogol story a satiric look at bureaucracy, the Leskov novel an examination of the oppression of women and stultifying provincial life in the Russia of that time.

Shostakovich began work on The Nose soon after the stupendous success of his First Symphony, which was written as his graduation piece at the Leningrad Conservatory and first heard in May 1926, before the composer turned 20 years old.

Even by the standards of Mozart and Mendelssohn, Shostakovich’s early symphony is remarkable for the maturity it reveals at such a young age, and it has remained one of his best-known works. It is almost as if the youthful composer decided to use his new fame to seize the opportunity to experiment. The Nose, as well as other compositions from this period, is daring in its combinations of different musical styles and its interest in avant-garde trends. The young Shostakovich was intimately aware of developments in musical circles in Europe. He was influenced by Stravinsky and Alban Berg, among others, and Berg’s recently completed opera Wozzeck was especially influential as he set about opera composition.

Based on the work of noted novelist Yevgeny Zamyatin and others, The Nose’s libretto follows Gogol’s story fairly closely. A St. Petersburg barber, Ivan Yakovlevich, is shocked to find a nose baked by his wife into his breakfast bread the day after he has shaved one of his regular customers, a bureaucrat by the name of Kovalyov. The barber is berated by his wife, and then embarks on a comical and fruitless effort to get rid of the nose, including an attempt to throw it into the Neva River.

Meanwhile Major Kovalyov wakes up and finds to his horror that his nose is missing. He runs off to search for it, only to find it walking about in human form in the uniform of a higher official who refuses even to discuss with someone of lower rank. A panic-stricken Kovalyov then makes some other unsuccessful attempts to resolve the situation, including an effort to place a newspaper classified ad for his nose.

When, after much confusion, the nose is eventually returned, Kovalyov is unable to reattach it to his face. In the last act he discovers the nose back where it belongs, and goes out to celebrate and show it off.

Shostakovich was undoubtedly drawn to this story by its satirical aspects. Gogol was revered as a founder of Russian literary realism. His tale of bureaucratic smugness, hollow men and moral obtuseness struck a chord in the late 1920s in the Soviet Union. The goals and ideals of the October 1917 Revolution were threatened by the rise of a privileged bureaucracy and the growth of inequality, which was one of the byproducts of the New Economic Policy as it was implemented in that period.

While Shostakovich was not a member of the Bolshevik Party and took no active part in politics, he traveled in intellectual and cultural circles where the attacks on the Left Opposition led by Leon Trotsky were noted with foreboding. The mounting political repression in the country was not yet manifested in the same way in the cultural sphere. Especially in the area of what is usually termed absolute music, the political straitjacket later imposed by the Stalinist regime in the form of “socialist realism” was still a number of years off.

Throughout the 1920s, organizations espousing the anti-Marxist theories of “proletarian culture” had been active in the fields of art, literature and music, but they did not play an official role and, indeed, were strongly criticized by both Lenin and Trotsky. As the bureaucratic degeneration of the Soviet Union continued, however, attacks on “elitism” and “foreign” influences grew, and denunciations of compositions that were not considered immediately accessible to a mass audience became more frequent.

The Russian Association of Proletarian Musicians (RAPM), one of the organizations espousing “proletarian culture,” denounced The Nose after its performance in a concert version in 1929. When the opera itself premiered in January 1930, critics attacked its use of atonality and its other experimental qualities.

The Nose disappeared after its original run of performances. It was not staged again until 1974, only a year before the composer’s death. It has in recent years been heard more often, including under the baton of noted Russian conductor Valery Gergiev, who recorded it last year with St. Petersburg’s Mariinsky Orchestra, and also led the performances at the Met.

Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, as many classical music listeners know, had a much more serious impact on the fortunes of Shostakovich under Stalinism. Although the opera was received enthusiastically when it premiered in 1934, and soon was performed more than 200 times, by 1936 the opera’s themes were seen as dangerous by the regime.

In a well-known historical incident, Stalin heard the opera in performance on January 26, 1936, and two days later Pravda (official organ of the Central Committee of the Communist Party) printed an unsigned editorial denouncing it as “Muddle instead of Music.” This was the beginning of nearly two decades in which Shostakovich lived in fear much of the time. It was also the period, not coincidentally, during which the Stalinist terror was organized, a terror that would take the lives of literally hundreds of thousands of revolutionary opponents of the bureaucracy, as well as of the intelligentsia and others who were either considered a threat or were swallowed up by the brutal logic of the Stalin’s paranoia, through which the bureaucracy maintained its grip.

The premiere production of The Nose at the Met is part of the effort led by Peter Gelb, general manager of the opera house for the past four years, to inject some badly needed imagination and vitality into its productions. Gelb has called on the talents of theatrical directors and others to put more emphasis on theater in the combination of theater and music that is the essence of opera.

Directing the new production of The Nose was the South African artist William Kentridge. A retrospective of Kentridge’s work, featuring drawings, sculpture, animation and theatrical design, including some work related to the production of The Nose, is presently on view at New York’s Museum of Modern Art.

Conductor Gergiev’s knowledge of this opera is second to none, and the performances, both of the Met Orchestra and the singers, were of high quality. The Nose makes unusual demands on any opera company. The current production features about 30 different singers in more than 70 separate roles, although in an opera that is one hour and 45 minutes long—three acts, including 16 scenes, without an intermission—obviously many of those roles are very small indeed. Leading the cast, in the role of Kovalyov, was Brazilian baritone Paulo Szot, who took a leave from his starring role in the current revival of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s South Pacific at the Lincoln Center Theater in order to assume this very different persona of the man without a nose.

The role of Kovalyov is a physically demanding one, and Szot did a good job of depicting him both in music and action. Other roles, including those of the police inspector, the barber and his wife, and the character of the nose itself, were also well done.

As to the music itself, the first hearing aroused interest. The combination of atonality and occasional orchestral interludes, lyricism and choral passages that serve to interrupt and in some sense relieve the relentless rhythmic intensity, cohere into a whole that fits well with Gogol’s story. The Nose is more experimental musically than Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, but it is characteristically Shostakovich. Amidst the clashing musical styles a distinctive voice emerges. The sardonic humor, use of folk melodies, somber introspection, wild waltzes and hints of popular music, for which the composer would become well known throughout his career, are all here.

Whether the production succeeds or fails as a whole is a more complex question. Kentridge is undoubtedly a figure of great talent and imagination, but it must be said that what he has done with The Nose works less than half the time. The scenes of Kovalyov’s frantic search for his nose, a growing mob joining this search at one point in a scene that suggests something of the growing crisis within society, all these are well done. The background animation and screen projections are another matter.

This is an extremely fast-moving and complicated piece of absurdist satire, as already indicated above in relation to the number of roles and scenes in the opera. The Met, in a very rare switch, supplied supertitles for much of the libretto in addition to the usual Met titles in simultaneous translation on individual miniature screens on seat backs. This was necessary so that the audience could follow the action without constantly taking its eyes off the stage.

Even with this addition, however, it was exceedingly difficult to follow and understand what was taking place. The combination of the regular sets, complex music and dialogue in English translation was a tall order to begin with. The addition of Kentridge’s video animation and screen projections made for an often-jarring effect. The viewer strained to follow the background but lost the music, or listened to the music and followed the dialogue, losing the rest of the production elements.

New York Times music critic Anthony Tommasini, commenting on The Nose, correctly pointed out that the importance of not losing sight of the role of the music in opera. “Directors have to remember that there is something inherently dramatic about singing,” wrote Tommasini. “Sometimes a great opera singer, just standing in place and singing great music beautifully, excitingly, can be extremely dramatic.” The late Lorraine Hunt Lieberson, in her amazing appearance at the Met as Dido in Berlioz’s Les Troyens a few years ago, was one of the most powerful examples of this truth.

In addition, some of Kentridge’s design and animation choices seemed questionable to this writer. As a feature article in the opera program explained, “According to Kentridge, the projections on the screens behind and around the singers will serve to contextualize the piece, as well as help explain the backstories of some of the random characters that pop up throughout the opera. Text, slogans, lists of Soviet bureaucratic hierarchies, and other assorted early Soviet propaganda will flash across the stage, along with footage depicting the nose’s imagined behind-the-scenes escapades, which aren’t ever really mentioned in the story or the opera.”

This mouthful of a description indicates one of the problems. In a work such as this, the idea of adding material that isn’t even “mentioned in the story or the opera” seems unnecessary and overdone.

Kentridge, with good intentions, tried to use photos and animation to relate Gogol’s story to Soviet reality. He wanted, according to the program, to “make the analogy” between the disappearing nose and “the kinds of erasures and changes to photographs of that period.” The program quotes the director: “It’s like those retouched photographs we’re all so familiar with—Trotsky’s in the photo, then he gets retouched out and he’s disappeared.” Elsewhere the program describes Kentridge’s vision of the opera as “more steeped on the specific moods and happenings of the early Soviet Union in the 1920s and 1930s—a period of wonderful experimentation followed by a crackdown after Stalin took power.”

This is a breath of fresh air compared to the usual ignorant claims that Stalin was the loyal pupil of Lenin and that the October Revolution ushered in tyranny and dictatorship. The distinction between the early years of the Revolution and what came later is not made clear from the overly detailed animation and photography, however. In fact, the overall impression created by juxtaposing scenes of genuine mass demonstrations and other events from the early period of the Revolution with the story of The Nose is one of general confusion. One critic approvingly called it the picture of a society that is “drowning in propaganda.”

Despite these weaknesses, the appearance of The Nose at the Metropolitan Opera was an important and on the whole positive event. The Met remains very much an elite institution almost entirely dependent on its wealthy patrons and on filling its nearly 4,000 seats. Its programs still tend toward the conservative side. The 2009-2010 season had few operas dating from the last 100 years. Two of these were The Nose and Leos Janacek’s From the House of the Dead, a remarkable work also based on Russian literature (Fyodor Dostoyevsky), and was composed at almost exactly the same time as The Nose. In Janacek’s case, however, it was his last opera, not his first. The extraordinary Czech composer, who died in 1928, was more than 50 years older than Shostakovich.

Another important new production at the Met was John Adams’ Doctor Atomic, the story of J. Robert Oppenheimer and his role in the creation of the atomic bomb.

Without in any way slighting the immortal operas of the 19th and early 20th century, the development of the form and of new audiences requires bolder programs, musically as well as theatrically, that are affordable to students and youth. It is true that most contemporary operas are not very memorable. Still, there are Britten, Janacek, Weill, Prokofiev and others, in addition to Shostakovich.

The Met’s staging of livelier works such as The Nose seems to be a response in part to a pressing problem, the divide between high and low culture, and the mausoleum-like character of many establishment arts institutions. However, the difficulty at heart is societal, rooted in enormous social inequality and the inaccessibility of culture to wide layers of the population. The production of newer, more innovative work is all to the good, but that by itself is never going to solve the fundamental problem—the answer to that lies outside opera.